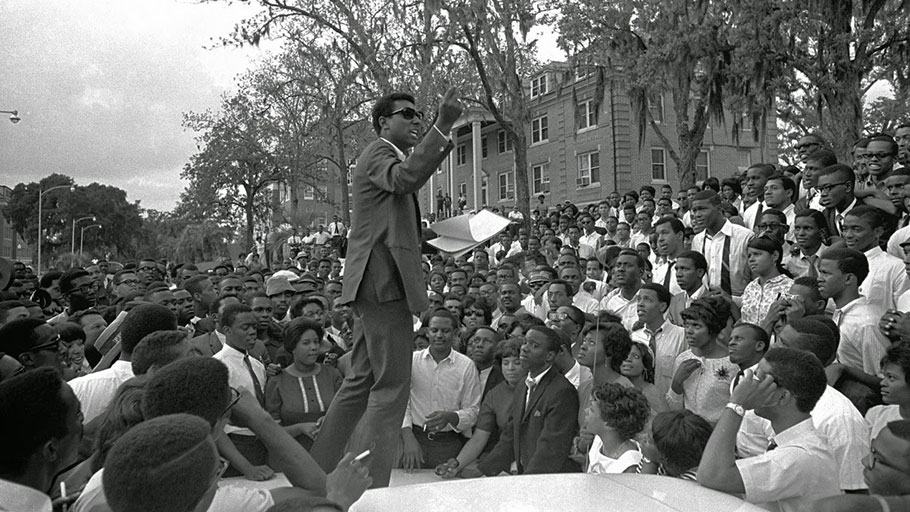

Stokely Carmichael of SNCC at Florida A&M University, 1967. (Photo: AP)

The Black Studies movement, inaugurated in the late 1960s by student- and community-based demands for a “more relevant education,” represented the intellectual expression of political Pan-Africanism in United States colleges and universities. According to St. Clair Drake, “Pan-Africanism ha[d] provided a distinct global focus for Black Studies since the programs became a part of the campus scene in the late sixties and early seventies.” Student agitation for a culturally legible education with utility beyond the “ivory tower” fundamentally challenged the imperialist, white supremacist, and bourgeois ethos of the traditional disciplines. These strivings emphasized economic development of local and global communities, Black self-determination and racial equality, and the importance of an internationalist framework to connecting African-descendant struggles for liberation in the global North and the global South.

Black student militancy undergirded by Pan-Africanist ethos manifested in the characterization of their struggles regarding Third Worldism, with San Francisco State College leading the way by founding the Third World Movement in 1968. Black students drew upon the anti-imperial, anti-colonial, and anti-racist insurgencies in Africa, the Caribbean, and the global decolonizing world more broadly, as a “defining political metaphor” for their position as an internal colony. Like Pan-African movements for independence, sovereignty, and an equal status in the global community, the Black student movement asserted itself as culturally and socially equivalent to the dominant power structure, and thus deserving of recognition, legitimacy, and academic representation of their realities.

The “intellectual spirit” of Black cultural nationalism also animated struggles for Black Studies on predominately white and historically Black college campuses alike. Black Studies was envisioned as a space to confront the “cultural apparatus” of the United States and to counterbalance the historical effects of white “cultural particularism” that denied the validity of competing values, standards, and epistemologies. According to Harold Cruse, it was only through a sustained investigation of Black history and culture that Black people could understand their position in American society, and could work toward democratic and equitable inclusion.

Manning Marable concurred that the function of Black Studies scholarship was not merely to celebrate Black heritage and racial self-esteem in the abstract, but instead to utilize history and culture as tools for the eradication of oppression and the fundamental transformation of society. Black Studies, then, was a means of redefining the dominant narration of US culture and history by prioritizing the significant contributions of Black people. The excavation of Black history and culture would facilitate social uplift, combat white racial chauvinism, and cultivate the cultural resources to wage the battle for human rights and self-determination.

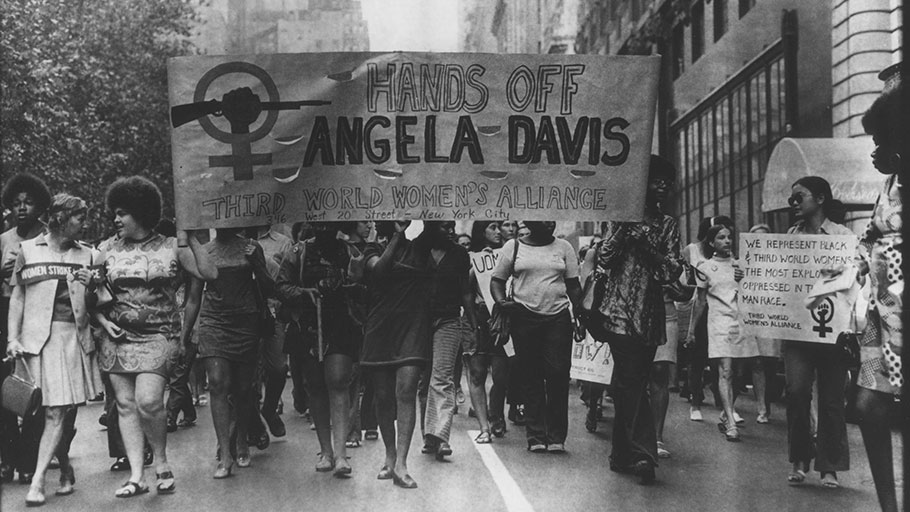

Members of the Third World Women’s Alliance in 1972. (Photo: Luis Garza)

As Black students were picketing, striking, and occupying buildings on college and university campuses, Black feminist organizations were bourgeoning to assert the unique positionality of Black women. The Third World Women’s Alliance (1968), National Black Feminist Organization (1973), Combahee River Collective (1974), and Black Women’s United Front (1975), for example, sought to organize Black women across class to combat forms of social and political subjugation that resulted in their “triple jeopardy.” The more radical of these organizations combined anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-capitalism, and anti-imperialism to articulate a program that directly addressed the concerns and experiences of Black women in the struggle for self-determination, an end to economic exploitation and alienation, and the eradication of racialized oppression. Such activism was concomitant with the introduction of Black feminism in the US academy.

The intervention of Black feminism into Black Studies, and the creation of Black Women’s Studies, aimed to challenge Black men’s overdetermination of scholarly inquiry into the history, culture, and social problems of Black people. The inclusion and centering of Black women in discourse and knowledge production aimed to clarify what was obscured by their exclusion; to expand often-reductive interpretations of Black social life due to the elision of gender analysis; to interrogate how certain theories and approaches erroneously and unnecessarily placed Black women and men in conflict and competition; and to reveal whose interests were served in defining Black men as the paramount subject of liberation, on the one hand, and pathology, on the other.

Moreover, contemporaneous with the institutionalization and “professionalization” of Black Studies in the 1980s was the popularization of African diaspora theory. According to George Shepperson, the latter helped to explain the condition and future of African descendant people against the backdrop of African independence movements. Tiffany Patterson and Robin D.G. Kelley held that African diaspora theory emerged as both a political and analytical term concerned with the dispersal of African people and their role in building the New World. While earlier articulations of diaspora emphasized continuity, unity, rootedness, the nation frame, and shared notions of Africanness, as “globalization” became the term to reflect the ethos of the post-1970 era, the focus shifted to fluidity, multiple temporalities, and exchange between sites within the diaspora. According to James Clifford, decolonization, increased immigration, and global communication and transport required a more “polythetic” definition of diaspora, insofar as its constitution moved beyond those who were descendants of enslaved Africans.

The polythetic iteration of the African diaspora offered a “trans-temporal dialogue” of contestation, negotiation, and refashioning. It became a way to critique absolutism while keeping the idea of ethnicity intact—what Paul Gilroy called anti-anti-essentialism. Instead of the retention of essential elements from an African past, an emphasis was placed on cultures being made and remade, with Black identity being constructed from multiple and different sites. Furthermore, African diasporic identity came to be understood as the means by which people of African descent could navigate how they were positioned by and in the narratives of the past, and engage in cultural retrieval and reconstruction. As such, connections within the diaspora became just as important as ideas of origin, which required the decentering of Africa as homeland.

Paul Gilroy at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 2015. (Photo: Heike Huslage-Koch, Wikimedia Commons)

By the late 1980s, when Black Studies had become more institutionalized, there was a noted and distinct absence of Marxist; historical materialist; and critical political, economic analysis of blackness in its formulation. The discipline tended to ignore or marginalize the study of economic agency and resistance, the failure of the market, the relations between labor and exploitation, and economic development (or the lack therefore) in US Black communities and the Black world. The organization of Black Studies around the analytic of diaspora reified the cultural specifications of blackness through the trans-nationalization of the study of Black sociality and culture.

The shift in global accumulation—that is, the transformation of capital from its liberal to neoliberal form—precipitated by the 1973 world recession and oil crisis, the declining rate of profit, deindustrialization in the global North, and a looming debt crisis in the global South, had homologous, albeit geospatially specific, effects on all African-descendant peoples. The emphasis on cultural affinity and connection in Black Studies neglected the convergence of the material experiences in the structural organization of political economy among Blacks in the United States, Great Britain, Africa, and the Caribbean in the wake of a neoliberal agenda that produced a rollback of the state and its reformulation. Reaganomics, Thatcherism, and structural adjustment that accompanied the collapse of the socialist/communist alternative instantiated this neoliberal agenda and its effects. Despite this global restructuring, popular and scholarly understandings of American and diasporic blackness rejected critical political economy. In other words, Black Studies failed to incorporate a structural and material critique of globalization that could have provided a deeper understanding of how Black people have been linked historically through the global-axial division of labor.

Economists Patrick Mason and Mwangi wa Gīthīnji pointed to the overwhelming representation of the humanities in Black Studies, and the relative absence of the social sciences, especially economics; this was not always the case. In its early evolution, political economy and economic development were important sub-foci. However, by the 2008 publication of a special issue of Journal of Black Studies focusing on the role of political economy in Black Studies, only 1.75 percent of faculty members in the discipline were economists, and just over 1 percent of the courses offered were economics courses. As well radical Black political economists and the contributions of critical political economy to Black intellectual thought has been all but forgotten. According to economist Julianne Malveaux, “traditional and theoretical disciplinary formulations” of Black Studies have mainly been influenced by the exigencies of institutional accommodation, which are best served by the field’s cultural studies approach.

The distortions produced by the anti-Marxist and anti-materialist specifications of Black Studies erase and even negate the structural and material dynamics involved in the production, maintenance, and recapitulation of blackness over time and space. The discipline further evades and undermines critical, political economy by diverting research and scholarship away from the material conditions of Black abjection, dispossession, and exploitation. This is notwithstanding the reality that structural and anti-systemic modes of critique expose the actual circumstances of blackness—a revelation that is essential to a sustained anti-capitalist challenge that resists reinscription into the statist project of global accumulation.

Charisse Burden-Stelly is an Assistant Professor of Africana Studies and Political Science at Carleton College. She received a PhD in African Diaspora Studies in 2016 from the University of California, Berkeley. Her areas of specialization include race and political economy, Black political theory, antiblackness and anti-radicalism, and Black radical thought.