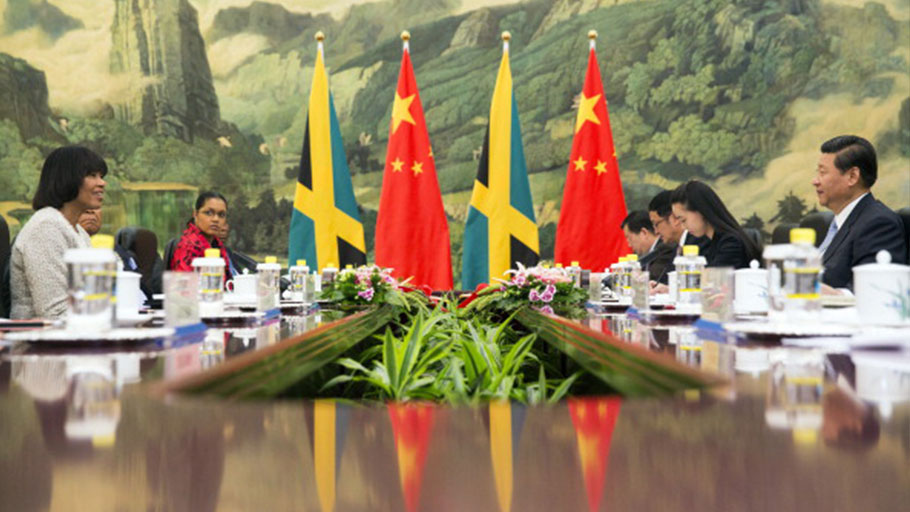

New friendship or new colonialism? Photographer: Adrian Bradshaw/AFP/Getty Images

The growing competition between Washington and Beijing for influence offers opportunity and perils.

In his recent swing through Latin America, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had some stern words for regional leaders about Chinese bearing gifts. “Malign practices,” “predatory loans,” envoys toting “bags full of money” to bribe officials: Such were the hazards of consorting with the would-be mandarins of the Americas, he said in April.

But listen closely and you’ll catch a more plaintive beat: It’s a courtship gone sour. If the United States hoped to enlist hemispheric neighbors in its rolling quarrel with China, that effort has now hit a familiar reef. Beijing’s far-flung strategic trade and investment deals have taken its envoys deep into the Americas, from Patagonia to the Andes and, more recently, uncomfortably close to U.S. shores.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is now in full force across the Caribbean, finding takers among poor island governments who feel snubbed and underappreciated by the hegemon next door. While the diplomatic rhetoric has turned testy, the rivalry between the world’s two leading economies may be the best opportunity the Caribbean has seen in years to parlay geopolitical jockeying into collateral advantage.

Beijing’s Caribbean pursuits began in earnest in 2013. That’s when President Xi Jinping met with 10 Caribbean leaders to herald a new era of cooperation, investment and loans. That was reggae to the ears of regional governments, which have struggled with the politically toxic combination of sluggish growth, high debt, fiscal imbalance and natural disasters. Consider that the Jamaican economy is only now emerging from more than three decades of low growth, high debt and scant investment. And while the Caribbean’s cache of commodities is meager compared to the haul in other BRI partners, Beijing’s lavish reception of visiting ministers and heads of state went neither unnoticed nor unrewarded.

Most immediately, the charm offensive peeled away the region`s historic ties to Taiwan. Panama, in 2017, not only ended decades-long support for the regime in Taipei; it went on to break off a lucrative free trade agreement. In 2018, El Salvador and Dominican Republic also decided to recognize China, the government in Santo Domingo doing so on the hush even as it closed a deal for Taiwanese military equipment. None of the three governments consulted with the U.S. over their diplomatic turnabout. Six Caribbean countries have since joined Belt and Road, with its promise of bounteous credit and zero tariffs on some 90% of traded goods.

China, sensibly, declared it had no interest in provoking Washington, least of all along the island crescent touted as the U.S.’s “third border.” Yet the Caribbean incursion predictably comes with political undertone. Hence China’s gesture of launching a national development plan for Grenada, the island the U.S. invaded over its Cuban military advisers in 1983 and has mostly ignored ever since. The Chinese military has also been active in the Caribbean basin, selling patrol vessels to the Trinidad & Tobago navy and hardware to the Jamaican armed forces. Several island nations are collaborating with China on regional security.

“The fact is, China has managed to leverage its role as a champion of forgotten and neglected nations, and found willing clients,” said Margaret Myers, who runs the Asian Latin America program at the Inter-American Dialogue. “Whether it’s climate change or trade, they’re working to establish connections, and Belt and Road purports to offer an alternative model.” It hasn’t hurt that even as the U.S. and European Union bought few Caribbean goods in the first quarter of 2019, Chinese import demand was still growing.

Not everyone sees the Chinese as developing world champions. Local companies complain that the Chinese import wage slaves instead of hiring locally and crowd out national contracts by low-balling bids. In a 2017 video still generating comment on the web, former Jamaican national security minister Peter Bunting denounced the “new colonialism,” as China “took over” construction and architecture. Other critics warn of the fine print and conditions – importing Chinese labor and machines, multiyear tax breaks – written into finance agreements. “Chinese loans cannot compare to the low interest credit from the Inter-American Development Bank or the World Bank,” said one former official from a multilateral lender.

Yet one of the perks Chinese bring to the table is their ability as interlopers to disrupt the schemes of clubby insiders who leverage cronyism, hired muscle and padded contracts to game public works. Sandra Glasgow, now a business consultant, got a glimpse of that possibility as early as 2001, when she oversaw a $100 million tender to build the Technology Innovation Center at University of Technology Jamaica. A Chinese company won the contract, easily outbidding the local competition, then delivered the project before deadline.

The native construction “dons” were incensed, and even staged a nighttime shoot-up of the Chinese workers’ dormitory. But a taboo had been broken. “The work was excellent and quick, without many defects. That stood out,” Glasgow said. The Chinese have gone on to build highways, hotels and homes in Jamaica. One prize client is GraceKennedy Group, a signature Jamaican food and financial services conglomerate, which hired a Chinese contractor to raise a new headquarters in Kingston. Jamaica signed on to the BRI in April, a watershed for the largest Caribbean nation with historical ties to the U.S.

The China critics are still vocal, but the newcomers appear to be learning from their missteps elsewhere to lighten their footprint on a host economy, guarantee jobs for national workers and share contracts with native companies.

For all Washington’s warnings about predatory alliances, it left a vacuum that China has filled. U.S. aid to the region has dropped sharply, a trend accentuated under Trump, whose hemispheric attention has locked onto politically expedient targets like illegal migrants and narcotics. “The kind of support we used to look for from the U.S., the United Kingdom and Europe, we don’t get anymore. You kind of get the feeling the U.S. has dropped the ball,” said Glasgow.

Instead of pumping up the threats from afar, the U.S. might take China’s cue and turn its gaze back to friends and neighbors near its shores. Answering Belt and Road with enhanced aid and trade would already be a diplomatic win for an overlooked region. A few more regional diplofests at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort would help. For their part, Jamaica and its neighbors may not be able to match their suitors for negotiating leverage and realpolitik, but they have a lot to gain by learning how better to play the field.