By Arit John

This Saturday marks the 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that, for a time, desegregated American schools. And if you listen to experts talk about Brown’s legacy, you’ll typically hear them point out that schools are more segregated than ever, thanks to a combination of bad housing policy, white flight to the suburbs and lax court enforcement of desegregation orders.

But the problem now isn’t just that many schools have reversed the desegregation gains of the ’70s and ’80s. It’s that white and black students get different treatment—and end up performing at different levels—in the few schools that they attend together. In other words, even where Brown has seemed to succeed, serious racial inequality persists.

Minority families petitioned for integration in the 1950s in part because white schools were better funded. But, as a majority of the Court’s justices would later argue, a disparity in resources wasn’t the only problem. Segregation also had a psychological aspect on students, making education inherently unequal. In the unanimous Court’s opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that “to separate [black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority … that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” Segregation, he added, denoted a sense of inferiority that “affects the motivation of a child to learn.”

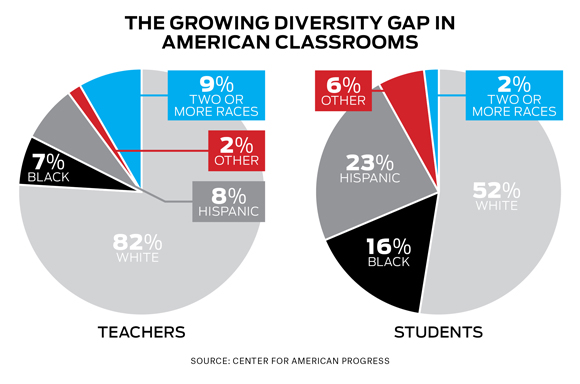

Today, even in schools that have achieved some level of diversity, there’s evidence that students of different races are still being treated differently. A 2007 study from the Journal of Educational Psychology analyzed dozens of previous studies, spanning more than three decades, on how teachers interact with different kinds of students. Researchers found that, overall, teachers’ expectations and speech varied depending on the race of the student. Teachers directed the most positive behavior, like questions and encouragement, to white students.

A 2012 study from the American Sociological Association found, “Substantial scholarly evidence indicates that teachers—especially white teachers—evaluate black students’ behavior and academic potential more negatively than those of white students.” The study analyzed the results from the Education Longitudinal Study, a national survey of 15,362 high school sophomores, as well as their parents and teachers. Again, the evidence showed a bias among white teachers that favored white students.

One problem with teachers evaluating minority students more negatively than white students is that those teachers, along with standardized tests, are the ones who decide who gets recommended for remedial classes. African American and Hispanic students are more likely to get sorted into less competitive education tracks. And, if the evidence is right, it’s not because those students on average happen to be performing worse. A 2005 paper from the University of Illinois Law Review noted that school tracking assigns students of color “unjustifiably and disproportionately to lower tracks and almost excludes them from the accelerated tracks.”

One problem with teachers evaluating minority students more negatively than white students is that those teachers, along with standardized tests, are the ones who decide who gets recommended for remedial classes. African American and Hispanic students are more likely to get sorted into less competitive education tracks. And, if the evidence is right, it’s not because those students on average happen to be performing worse. A 2005 paper from the University of Illinois Law Review noted that school tracking assigns students of color “unjustifiably and disproportionately to lower tracks and almost excludes them from the accelerated tracks.”

The re-segregation of schools in the wake of lax enforcement of Brown gets a lot of attention—and for good reason. Studies have shown that schools with a majority of minority students and poor students tend to have fewer resources, and that black students who go to integrated schools have better academic outcomes than students in segregated schools. But if the goal is to make sure education is neither separate nor unequal, then policymakers also have to look at the way students of color are being treated in diverse schools. Desegregation might be the easy part.

Arit John is a journalist based in New York City