“FROM BEGINNING TO END – A NEW WORLD MAN”

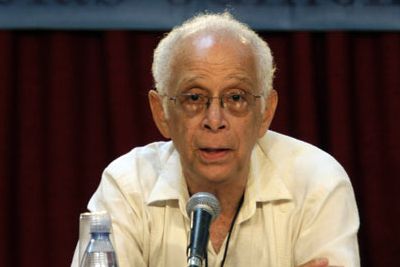

A TRIBUTE TO PROFESSOR NORMAN GIRVAN

BY DAVID ABDULAH

GENERAL SECRETARY, OILFIELDS WORKERS’ TRADE UNION

AT THE SERVICE IN THE CELEBRATION OF HIS LFE

THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES, MONA

SATURDAY MAY 3RD, 2014

I begin this tribute to Norman Girvan, a friend and a comrade, with the words of a great Jamaican literary figure, Dennis Scott. It’s his poem “Hatch: Or, The Revolution Viewed as an Exploding Library”

This is a stone.

These are the men climbing it.

They eat their way up its face

spitting out bits of earth and blood. When they are tired

the stumps of their arms wedge

into cracks, they hang patiently till the next leg

of the journey can begin.

Nothing stops them. They come

like messages, poems, songs

about hunger.

Those words cannot run, or rub off.

Sometimes the rock shifts, scattering one

into the air. He falls

silently, over and over, too tired to shout.

They know what to do when they arrive.

The holes have been prepared

by time, pecked open

into honeycombs: a library of dreams.

They will place themselves, like documents.

Fused.

They will wait for the fist, and the fire.

That stone will open,

like a seed.

Norman Girvan was one of those men who climbed the stone. These were the men who emerged in the early 1960’s as The New World Group: a group of radical lecturers and students in the social sciences and arts, who saw the future of the societies into which they were born as being predicated on two critical factors – the need for Independent Thought and the emergence of a federated or integrated West Indies. From the youth of 18 as a student at the University of the West Indies, Mona in 1959 to the youthful Professor Emeritus whom we lost way too soon, from beginning to end of his adult life, Norman Girvan was a New World Man!

As with all human endeavours, not all “hang patiently till the next leg of the journey can begin”. Some eschewed their earlier positions and opted instead for the orthodoxy. But not Norman. In his comments at the Closing Session of the First Conference of Caribbean Economists at Mona in July, 1987, a Conference which Norman was a central figure in organizing as the First president of ACE, Professor Rex Nettleford had this to say:

“Happily, in papers dealing with the social implications of the development crisis and the theoretical constraints as well as policy institutions rooted in Caribbean reality, the primary need to look at ourselves through our own eyes has been in large measure met. The work cannot stop here. There is much more to be done. This is just a beginning. For the global reality looms large in the consciousness, dominates the vocabulary of the most resistant among us and continues to blur the vision of our own leaders who want to be Ronnie Reagans and Maggie Thatchers before they are themselves”.

In the almost three decades since, the reality of neo-liberal globalization which then had started to loom large has indeed become dominant, but Norman held fast and challenged the orthodoxy to the end.

And yes, “the rock has shifted” and some who started the climb with Norman “have been scattered into the air” – Walter Rodney, way, way too soon; George Beckford too soon and Lloyd Best more recently. And now Norman. We have been blessed with some of the most remarkable men and women who were New World in thought, word and deed and who are no longer with us today. At the risk of doing a disservice to many, let me share just a few names whom I knew and who were also friends and colleagues – kindred spirits really – of Norman: Dennis Pantin, Angela and John Cropper, Pat Bishop, Rex Nettleford, John La Rose and, above all CLR James. There must be quite a ruckus going on somewhere as these co-conspirators gather to discuss the issues of the day!

What then, we may ask, kept Norman Girvan going? A friend of mine, Trinidadian born US based, Professor Acklyn Lynch remarked many years ago that the Caribbean sadly lacked, at the level of our leadership, a sense of ethics and aesthetics. Norman possessed both the ethic and the aesthetic and he held fast to the old adage – “to thine own self be true” – so much so that he maintained a deep ethical conviction to be intellectually honest.

Norman himself gives us a real appreciation of what underpinned his sense of ethics and aesthetics. There was, firstly, the context in which he started his student life which propelled him into the pursuit of Independent Thought and which shaped his conviction that Caribbean integration was central to our development. And there was the influence of CLR James. But let Norman tell it in his own words:

“I was a student on the Mona campus of the University (then University College) of the West Indies…I remember it as a time of great excitement, tremendous ferment and heated debates. Imagine what it was like to be in a Caribbean populated by the likes of Norman Manley, Eric Williams, Cheddi Jagan, Grantley Adams and CLR James; Frank Worrell and Garfield Sobers; Arthir Lewis; Vidia Naipual and Roger Mais; Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and the ghost of Marcus Garvey; moreover in a world populated by the likes of Nehru, Nasser, Nkrumah and Nyerere, Tito, Sukharno and Mao Zedong.

A debate was raging over what form the West Indies Federation should take and what economic policies it should follow…The burning issues of debate were West Indian integration and identity, imperialism, decolonization, racism, socialism, democracy, mass party and economic development. There was a widespread sense that the emerging postcolonial order was in crisis. The question was – what course should national independence take?”

I wish to suggest that Norman consistently interrogated this question for his entire adult life for the postcolonial order is still in crisis. I shall return to this later. But let us continue with his narrative:

“On residence at Taylor Hall I was surrounded by Trinbagonians, Guyanese, Bajans, Antiguans and students from the other islands. The air was vibrating to the sound of Pan and enriched with the smell of Roti – sounds and smells that were to me new, unfamiliar, even exotic.

Looking back, I can see that I was in the process of being transformed from a Jamaican nationalist into a Caribbean regionalist…

This was the ambience in which CLR James came to deliver one in a series of Open Lectures.”

“I was a first year student, an impressionable youth, and the experience was unforgettable…’The great artist’, James said, ‘is universal because he is national’ – rooted in his or her society and reflecting and relating to the social forces of their time and place…Years later, as a graduate student in London, I was part of CLR James study group that met every week at his house in London to sit at his feet – intellectually and even literally…Individuals from the James Study Group were to develop ideas, scholarship and activism that influenced the course of development in the English speaking Caribbean in the early post-colonial years.”

(Inserted comment – Some of the members of that study group are here today: Richard Small and Joan French)

To this I wish to add his relationship in London with John La Rose and other Caribbean literary and artistic figures, which relationship helped to connect him with the work of people like Edward Kamau Brathwaite and Stanley French and the Caribbean Artists Movement in London.

So emerged a young intellectual named Norman Girvan: an intellectual in the sense that George Lamming has so often defined and reminded us, that is, one who is in the service of elucidating our own reality in order to transform it in the interest of the ordinary men and women of the Caribbean.

I think that we can now situate Norman’s contribution as one of the finest sons of Jamaica and the Caribbean. It explains his work in academia and in politics, both formal and informal. I will not describe his enormous body of works and how his life progressed – in his own words how “One Thing Led to Another – influences on my choices of subject and approach” – but simply to connect what I believe were his consistent sense of ethics and aesthetics to these works.

Norman’s commitment to Independent Thought naturally led him to being part of the New World Group and Chair of its Jamaica branch. It led him to study and write about the exploitation of mineral resources in Jamaica, Chile and Trinidad and Tobago; and to identify the role of transnational capital in this process of exploitation. It situated him within the ‘plantation school” of economists who so excited my generation of students of economics: the school who seemed, like our great West Indian bowling attacks – Ramadhin and Valentine, Hall and Griffith, Roberts and Holding, Walsh and Ambrose – to hunt in pairs. I refer to (Havelock) Brewster and (CY) Thomas; (Alistair) McIntyre and Watson; (Norman) Girvan and (Owen) Jefferson; and of course (Lloyd) Best and (Kari) Levitt. (George) Beckford, perhaps like Malcolm Marshall, was always partnered with the other greats but not always consistently paired with one. This pursuit of Independent Thought also took him outside of the region: it opened him to the realities of Latin America and to its Open Veins. It also took him to Africa where he worked with Samir Amin at the UN’s African Institute for Development and Planning, located in Dakar, Senegal. It also led him to doing considerable research with Guyanese political economist Maurice Odle on technology transfer and MNC’s – first in a regional study and later at the UN Centre on Transnational Corporations.

Norman walked the talk of commitment to Caribbean integration. His entire teaching life was at the University of the West Indies. And it didn’t matter which campus – he started and ended at St. Augustine so, my Jamaican friends, Mona was but an interlude! He founded, together with GBeck, and led the seminal work of the Association of Caribbean Economists (ACE), which organization Judith Wedderburn nurtured so carefully. Then, in 2000 he moved to the position of Secretary General of the Association of Caribbean States. This was at a critical moment in Latin American politics (Hugo Chavez had only just been elected President of Venezuela and Lula started his Presidency in 2003, and these ushered in an era of the left taking office in Latin America). The work at the ACS was consistent with Norman’s vision of the Grand Caribbean as was his role as Special Envoy of the Secretary General of the United Nations in the Venezuela – Guyana border dispute. Latterly, he produced a formidable work on a roadmap for, and the imperative of implementing, the Caribbean Single Market and Economy.

The requirement of our radical intellectuals to walk the talk was evident throughout Norman’s life: from his work with the New World Group and Abeng in the 60’s and early 70’s to a sense of duty to contribute to the albeit fleeting opportunity of shifting the development agenda provided by the Michael Manley government be it through the Jamaican People’s Plan (with Mikey Whitter and GBeck) or as Head of the National Planning Agency.

Freed of the need to be in a formal institution, the last decade of Norman’s life was perhaps the period of greatest activism. He was a founding member and Chair of the Cropper Foundation; and a Board member of the South Centre working with colleagues on sustainable development. He led campaigns in solidarity with Haiti – to provide support in the aftermath of the earthquake and in the movement for self- determination: against imperial intervention in the form of both MINUSTAH and so-called post earthquake reconstruction driven by forces outside of Haiti. And, in the months just before his accident, Norman led the regional movement against the abomination of the Dominican Republic’s decision to make tens of thousands of Haitian descendents in the DR stateless. It was his way of saying, in the words of the calypso bard, David Rudder, “Haiti, we’re sorry’.

This activism was seen at its brilliant best in his campaign to initiate debate and educate Caribbean citizens, mobilize civil society and influence governments on the so-called Economic Partnership Agreement between Cariforum and the European Union. He suffered many a dogmatic attack against him for pursuing this campaign, but he pursued what he knew to be right and intellectually honest, consistent with his ethical position of Caribbean integration and sovereignty based on Independent Thought. He will, I am sure be vindicated by time.

This commitment to challenge the orthodoxy was naturally expressed in his solidarity with the revolutionary processes in Cuba and Venezuela. And as with all revolutionary solidarity, it was mutual and repaid by both Venezuela and Cuba in the last month of Norman’s life when he was in a moment of need.

The influence of CLR was also evident in Norman’s unbelievable discipline (he always produced completed papers and lectures; issued and then replied immediately to emails, while chastising those like me who didn’t) and in the commitment to propagating ideas through a newspaper: in the early days it was literally paper – New World Quarterly and Abeng; and then, quite remarkably for one of his generation, through the internet: a magnificent website –normangirvaninfo; regular blogs; thousands of email exchanges; and the weekly e-newsletter “1804 CaribVoices”. He saw the importance of nurturing a new generation and not just worked with graduate students, but assisted in developing them into activists by lecturing and speaking all over the region whenever invited, traveling tirelessly and producing numerous addresses and papers. It was indeed, the “library of dreams” of which the poet spoke.

In all of Norman’s work in the past decade he has, with all his tremendous intellectual capacity, critiqued the present neo-liberal capitalist paradigm and its deleterious effects on Caribbean sovereignty and the welfare of the ordinary men and women of the region. This is why I say that he was New World till the very end. But he makes the point best:

“My point is that the New World mission of intellectual decolonization is more relevant than ever because intellectual colonization is alive and well in Mona and St. Augustine and Kingston and Port of Spain. The methods of intellectual colonization are the conditionalities of the international lending agencies and donor countries, their financial surveillance, their technical reports on our educational system and our health care system and our agricultural policy and our public sector reform. The methods are the daily bombardment from the global media, it is scholarships and fellowships and travel grants that do us the favour of assimilating their worldvew, and it is consultancies given to scholars where they define the terms and we do the work…

Are we setting the agenda? Are we questioning the concepts that are handed to us and adapting them to fit our history and culture and cosmologies and inventing others when none of them fit? …So the fact that the world has changed since the 1960’s does not mean that it has not also remained the same. We have a different world from the world of New World but it is in many respects the old world that New World opposed”.

Thank you, Norman Girvan, one of the most fertile minds of our academy, friend of the region’s working people and poor, comrade of our social movements, fighter and believer in social justice, one who knew that another world is not only necessary but possible, mentor to a new generation of activists. And, above all, like all true revolutionaries concerned about humanity, Norman was simply a wonderful, wonderful human being!

Thank you Jasmine, Alexander, Alatashe and Ramon for sharing him with us.

Norman, you have, in the poet’s words “pecked open the honeycombs: a library of dreams”. You have ‘opened that stone, like a seed” and the next generation is, I assure you, “waiting for the fist, and the fire”.

I end with the words of another legendary Caribbean poet, Martin Carter:

“Dear Comrade

If it must be

you speak no more with me

nor smile no more with me

nor march no more with me

then let me take

a patience and a calm

for even now the greener leaf explodes

sun brightens stone

and all the rivers burn

now from the mourning vanguard moving on

dear comrade I salute you and say

death must not find us thinking that we die”

Walk Good, my friend!