By Herb Boyd

By Herb Boyd

Special to IBW

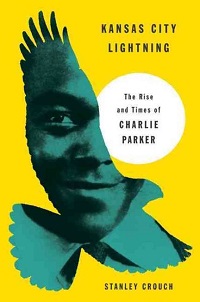

Bird watchers, not those ornithologists armed with binoculars looking for the latest rare specimen on wing, but jazz lovers eagerly awaiting the arrival of Stanley Crouch’s study of Charlie “Yardbird” Parker, the wingless immortal, can now exhale. Crouch’s biography, Kansas City Lightning—The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker is finally here after some thirty years of gestation.

A caveat should be noted in this arrival, however: the book mainly deals with Parker’s formative years, his coming of age in the region of his birth, a brief sojourn to Chicago, and his initial brush against New York City where his artistic genius will truly flower. Let us hope that Crouch won’t take as long to deliver this significant phase of Parker’s life.

In fact, it may take as many as three volumes to capture Parker’s furious passage among us because he amazingly packed the length of three lives in his monumentally productive 34 years. Crouch expends a lot of time on these early years as Parker searches for his muse, learns the intricacy of the alto saxophone, and wrestles with the demon of addiction that would occupy, and possibly intervene, so much of his quest for perfection.

Crouch’s biographical style is unique and some readers looking for a rather conventional approach might find it disconcerting, particularly his more than occasional riffs from the narrative in order to extend a metaphor, to contextualize an incident, or merely to flex his literary muscles. These moments might be seen, in musical terms, and especially within “Bird” lore, as Crouch’s “Thrivin’ on a Riff.” Exemplary of this notion is when he dips back into the distant past to outline the territorial development of the far west with the explorations of the Spanish conquistadores, most notably Little Stephen or Estevan, the scout out front leading a legion headed by Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. It’s a nice piece of arcane American history unknown to most readers, and the riff could have been given an even deeper jazz resonance with mention or citation of Lord Buckley’s bebop monologue of the same adventure.

Sometimes the riffs are a bit too long but the best of them are short takes as he does on recounting the pummeling heavyweight Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber,” took from Max Schmeling in 1936. “Those German rights kept landing in the ring at Yankee Stadium and the Alabama wonder began coming apart, round after round, three minutes each—the same length as a 78-rpm record, all a jazz band needed to make a complete musical statement,” Crouch writes. When Crouch adheres to the three minute riff, gathering the poignancy of the message, it serves him well and they don’t detract too much from the gist and rhythm of his story. These are delicious interruptions and reminiscent of a soloist inserting a fragment of “All This is Mine and Heaven Too,” in the midst of “Joy Spring.”

Riffs are fine when they are relevant to the flow of Parker’s life, and Crouch, for the most part, tends to keep these riveting asides under control, but when he overreaches it can be annoying; even so, he quickly redeems himself with a walloping follow-up as he does when taking a brief pause to discuss D.W. Griffith and the impact of his films with special attention to the monstrosity “Birth of a Nation.” Redundancy or repetition is another concern, which can be forgiven when it occurs in the same way musicians do it to underscore a melodic line or to accentuate a reference. His reflection on the influence and the importance of Lester Young is done in several chapters, albeit at different stages of his life.

Crouch is magnificent in discussing Parker’s creative maturation, his idolization of Chu Berry, the competitive encounters, his self-discovery and the discipline necessary to outshine his contemporaries and to establish himself in the pantheon of jazz greats. That process was often a challenging one and Crouch details it with insight and profundity. “Charlie Parker’s mind moved faster, and had a greater command of detail than that of the merely gifted,” Crouch relates. “And in order to serve his quicksilver consciousness—and the montages of passion that it demanded—he had to address not only his own physical limitations, but those of his instrument.”

And you discover that Parker was often tinkering with his horn “and such a proficient reworker of mouthpieces that he was soon filing away on those of his fellow band members and on any other saxophone players who trusted his skill,” Crouch adds.

Bird watchers have waited a generation for Crouch to live up to his promise, and if the second installment is as engrossing as the first, then we may cut him some slack for taking so much time vamping and thrivin’ on riffs. The speculation here, however, is that it won’t take as long because it will cover portions of Parker’s life with a lot more informants to help the biographer, and Crouch knows who these individuals are and it’s good bet he’s already got their stories down, and they should provide the thunder to the lightning.

Mastering improvisation is the mother’s milk of the jazz musician, and Crouch demonstrates that it is also a useful device for the storyteller at which he excels.