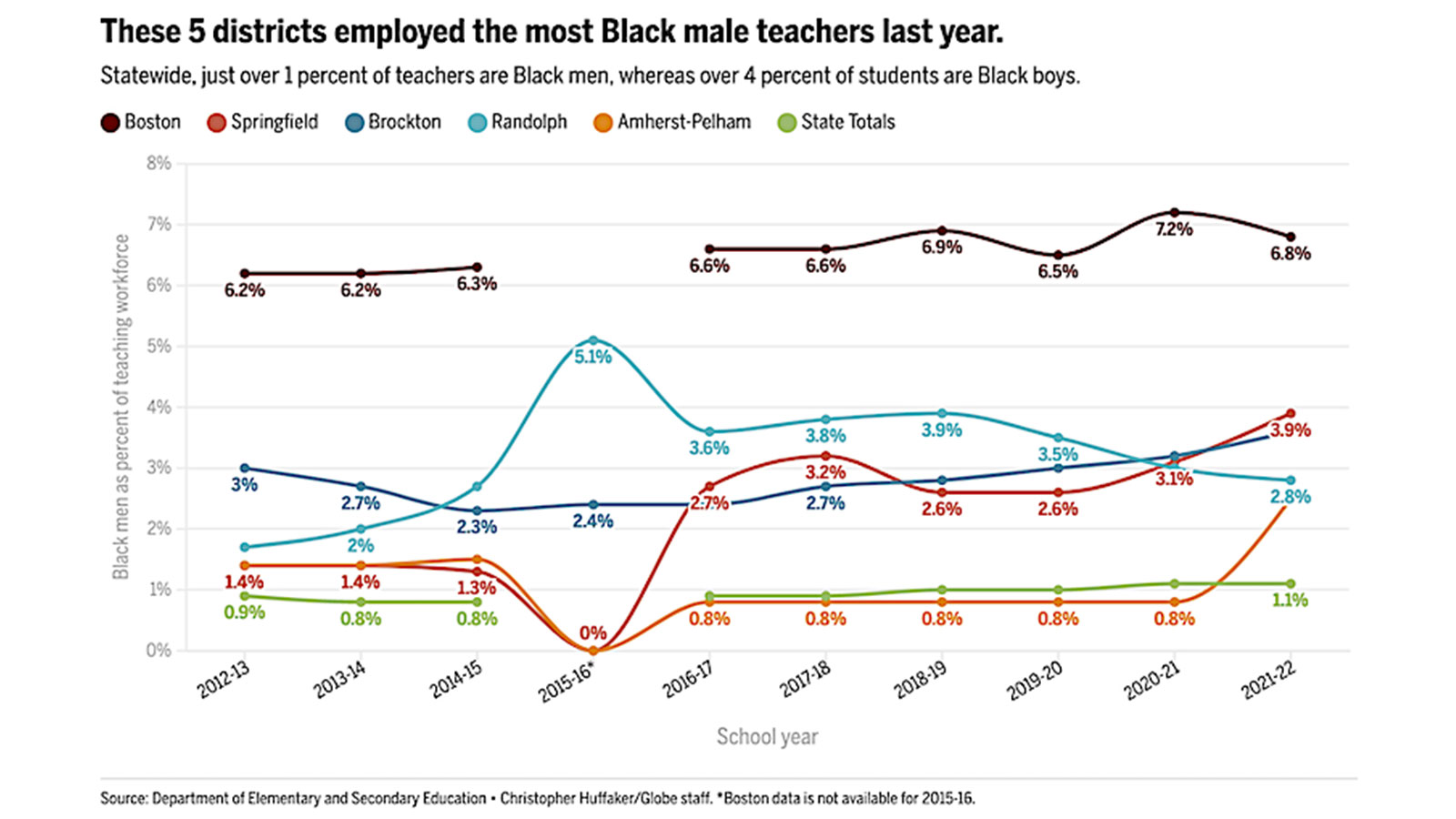

Statewide, just 1 percent of public school teachers are Black men. Even in Boston, which has the highest number of Black male educators, the proportion is just 7 percent.

By Christopher Huffaker, Boston Globe —

Over the last decade, Boston Public Schools has sought to diversify its teaching staff with a teaching fellowship, a training pipeline to help paraprofessionals and substitutes become classroom teachers, and affinity groups for underrepresented teachers, all aimed at retaining staff of color.

Yet those efforts have yielded just eight more Black male teachers, whose presence in city classrooms is considered particularly important.

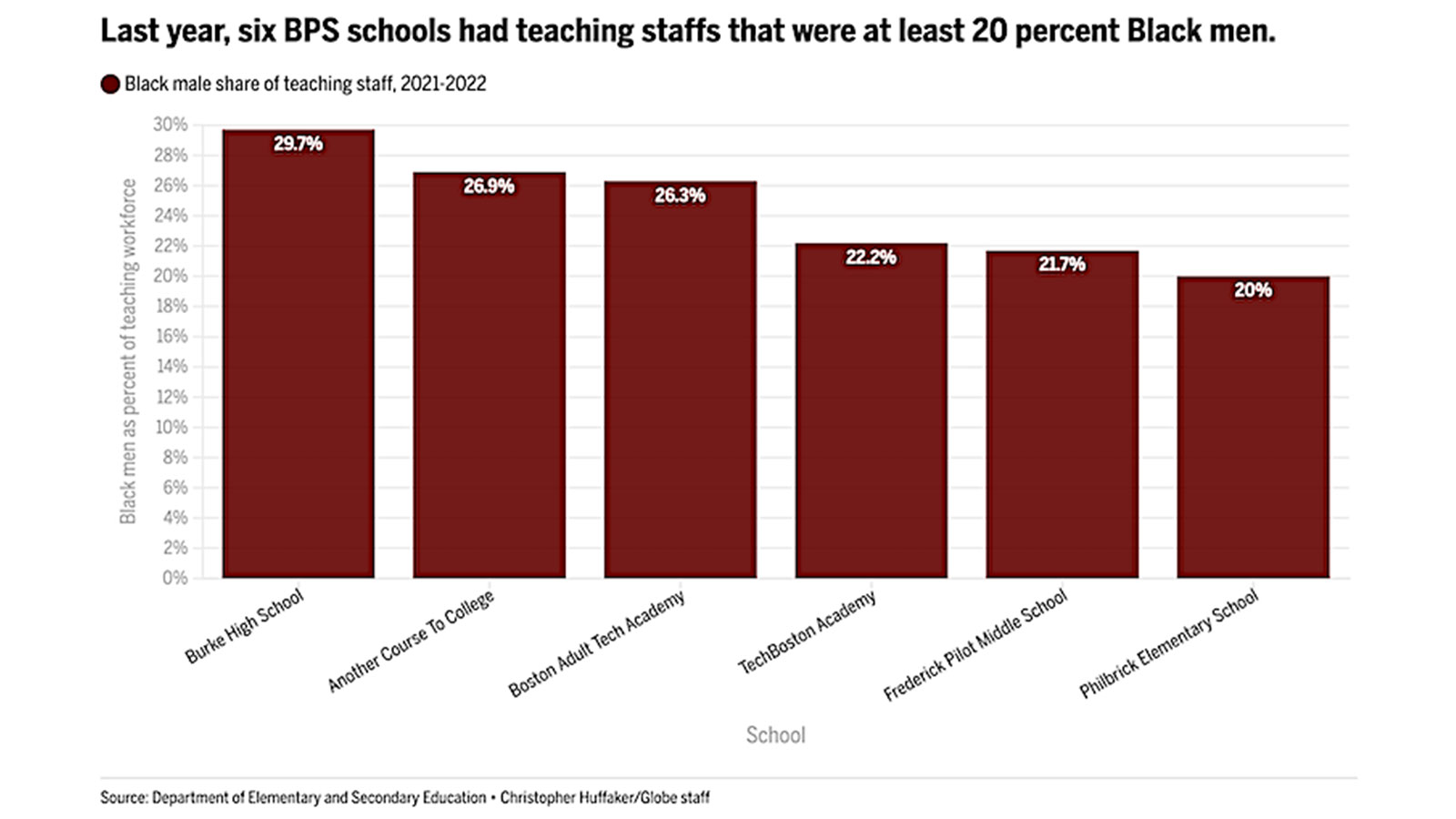

Research shows that Black boys taught by Black teachers are less likely to face severe discipline like expulsion or be referred to special education, in which they are overrepresented. Black boys make up about 15 percent of the district’s students — while Black men make up only about 7 percent of the teachers.

Black men currently working in the district, and advocates working to increase their number, said they have faced significant barriers to becoming and remaining classroom teachers. The minimal progress the district has made shows just how much still needs to change for Black boys to have the role models they need in the classroom — a change that could, according to research, help the district’s new leadership make good on its promises of closing achievement gaps.

Source: Department of Elementary and Secondary Education • Christopher Huffaker/Globe staff. *Boston data is not available for 2015-16.

Statewide, there are hundreds more Black men in classrooms than there used to be. Black men make up a larger percentage of the entire BPS teacher workforce than they did a decade ago — almost 9 percent more — as the workforce has shrunk, reflecting declining enrollment. But in both cases, the proportion remains small.

Overall, Boston has been slow to increase teacher diversity despite a nearly half-century-old court order mandating that 25 percent of the district’s teachers be Black. Districtwide, 85 percent of students are children of color, while only 41 percent of the district’s teachers are Black, Latino, or Asian American. Over the last five years, less than half of new teacher hires have been white, a district official noted.

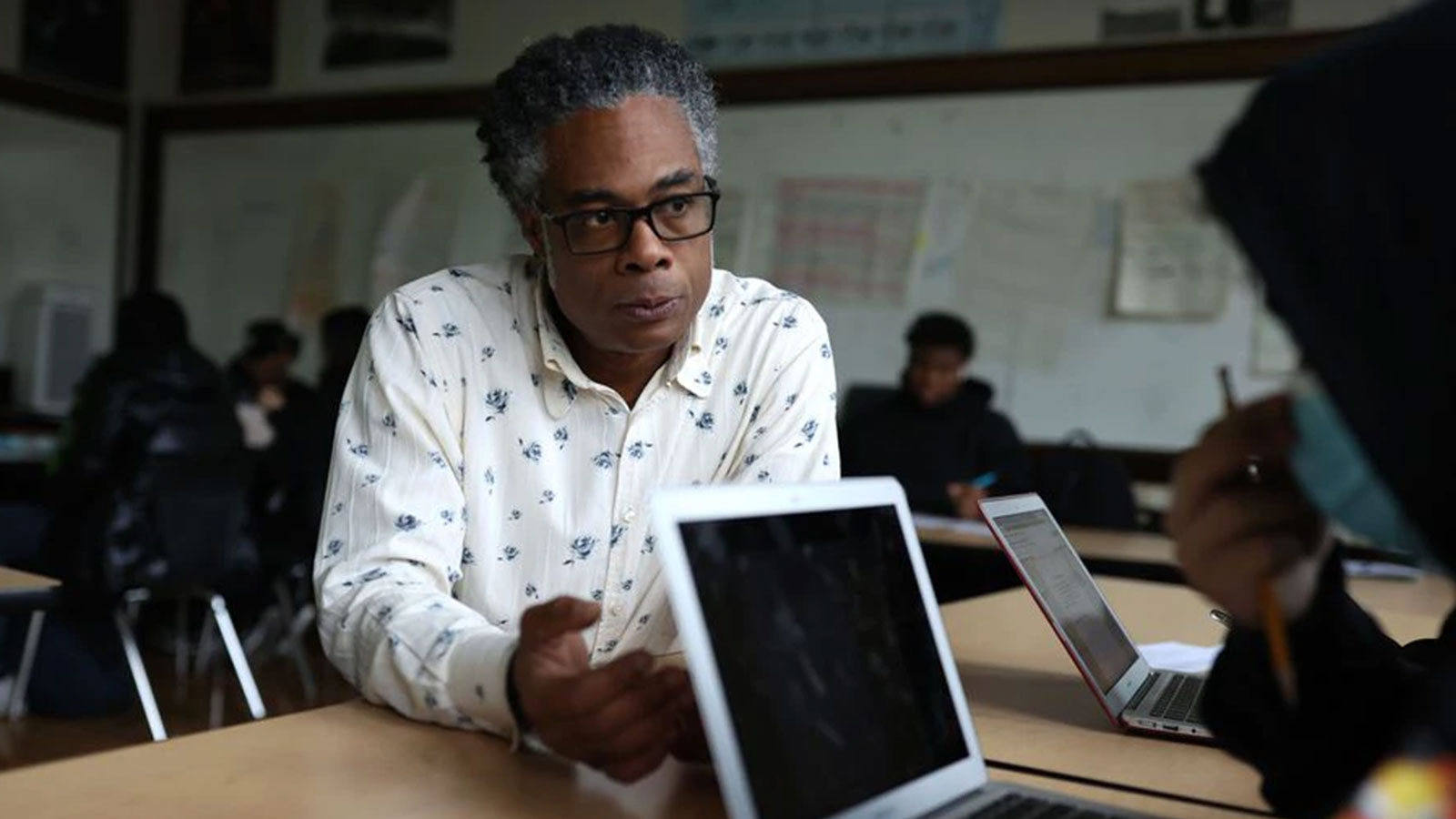

Marcus Walker, a humanities teacher at Fenway High School, worked with 11th-grade students. At Fenway, 18 percent of teachers are Black men. (Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

Most of the more than a dozen Black male BPS teachers interviewed for the story said they didn’t have a single Black male teacher growing up. Only one — who grew up in Indiana — reported having many, and the remainder rarely saw Black men in school outside of art classes, physical education, and roles where they were in charge of student discipline. They and others lamented the barriers to getting into and staying in the profession, including the lack of role models to become teachers, the cost and difficulty of getting licensed, and burnout from serving as mentors to many Black youths who have few Black men to turn to at school.

“I think back to my high school experience, there was a career adviser during my senior year, a young Black male,” said Wesley Ogbevoen, a 10th-grade math teacher at Snowden International School. “I found myself visiting his office several times during the course of the day. . . . What if he was one of my actual content teachers? Would I have been more willing to come to class on time?”

“I want to be who he was to me, but in the math classroom,” Ogbevoen said.

In addition to research showing the difference Black men can make on student achievement, Black men can also make school a more comfortable place for Black boys, who often view it as a hostile space.

Milton Lanza, a high school Spanish teacher at Dearborn STEM Academy who is in his first year of teaching, said a group of Black male students eats lunch in his classroom daily.

“That’s been organic,” Lanza said. “It’s been a lot of asking me about my past experiences, like what was college like for me, or how to find jobs. . . . The students really do care and I do want to be an example.”

Source: Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (Christopher Huffaker/Globe staff)

Many of the men interviewed for this story had nontraditional paths into the profession, as career changers or starting with other roles in the schools and going through the district’s “grow-your-own” teacher pipeline programs.

Such programs are part of how the district and state hope to make progress. BPS has drawn on state grants, including for the Accelerated Community To Teaching (ACTT) program, founded in 2014 to train candidates like school paraprofessionals, substitute teachers, and after-school program staffers. The program’s candidates of color have an unusually high passing rate on teacher licensure tests. Black and Latino test takers tend to pass the state’s licensure tests at lower rates than white test takers, state data show.

Andre Steward, a seventh-grade social studies teacher at TechBoston, said ACTT recruited him after six years as a substitute for the district. A Boston native who went to Catholic schools and a Metco high school, Steward didn’t encounter his first Black teacher until he arrived at Hampton University, an HBCU in Virginia. Being a Black man from the neighborhood helps him gain students’ trust, he said.

“They’re more likely to believe someone who they know has gone through the same things they have,” Steward said.

The district has ramped up efforts to recruit men of color, a district spokesperson said, including by growing its recruitment and retention teams.

“Our educators, namely our Black male teachers, have a profound impact on all of the students they teach and have made immense contributions to their school communities,” Superintendent Mary Skipper said. “As a district, it is critical that we continue to deepen our work in recruiting and retaining Black educators to enrich our students’ instructional and social-emotional experiences.”

If efforts to bring in more Black men are to work, more of them will have to stay in the profession, and at least two local organizations have sprung up since 2018 with the goal of making that happen. Leaders of groups geared at developing and supporting teachers of color, He Is Me, which focuses on Black men in particular, and The Teacher’s Lounge, which is aimed at teachers of color in general, cite the revolving door of teachers, and hope that building cross-school communities for Black men, who are often isolated in their buildings, can help.

Marcus Walker, a humanities teacher at Fenway High School, said it’s the students that have kept him coming back for 20 years.

On a recent morning, Walker greeted his 11th-grade students with fist bumps as they filtered into his class. When he caught a student looking up World Cup news rather than working on an assignment, he sat with him and talked about soccer for a minute before changing the topic to the reading. Walker encouraged the students to help each other out, drawing them into conversations about how they would react in the characters’ shoes.

“Race only gets you so far,” Walker said, but he comes in every day hoping to make some sort of breakthrough with at least one student.

“I see you as a human before I see you as a student,” he said. “That’s a big reason why I teach, to make that difference.”

Source: Boston Globe

Featured image: Marcus Walker