by Lurie Daniel Favors, Esq.

Wealth and Debt in Black Communities:

“If current economic trends continue, the average [B]lack household will need 228 years to accumulate as much wealth as their [W]hite counterparts hold today.” Joshua Holland, The Nation Magazine

When economist, author and former President of Bennett College, Dr. Julianne Malveaux, appeared in CNN’s documentary Black in America: Almighty Debt, she noted that personal and community wealth are based on cross-generational accumulation. Which means your personal and community wealth are supposed to grow when passed down from one generation to the next. According to Professor Steven Rogers:

Inter-generational wealth is “the monster wealth that started three, four, five of more generations ago and has been multiplying ever since; the kind of wealth that could, if the market conditions were right, start a retail chain, or buy swaths of real estate in the hottest market and develop a commercial residential complex or three.”

Like wealth, poverty is also a function of cross-generational accumulation. Just as wealth grows when passed down from one generation to the next, so do poverty and debt. And since the beginning of this nation Black people have been systematically and intentionally locked out of wealth creation opportunities.

Photo credit: Teaching it Forward – WordPress.com

Photo credit: Teaching it Forward – WordPress.com

The reason it would take Black people 228 centuries to build the same about of wealth as White people is because of slavery and the racist implementation of wealth development programs since the Civil War. When we understand this history, we know that we cannot return to business as usual.

American Government: Wealth Creator for Some – Wealth Denier for Others

Since its inception, the American government played a direct and active role in building wealth for White Americans. In fact, owning Black people was one of the earliest and most profitable forms of wealth generation in this country. By enslaving Black people and forcing them to work for free, for life, White Americans created an incomparable foundation for inter-generational wealth.

White people created the idea of racial differences and assigned value to the racial differences they observed. By the mid-1600s, Whites in the U.S. were using those differences to determine who could be a slave and who could not. American chattel slavery in the United States was an economic system that was based on race, in which members of the Black race were forced to give away their labor and members of the White race profited from that labor (whether or not they actually owned any slaves). Legislators across the country enacted laws supporting this belief and this locked Black people into America’s permanent economic underclass.

As a result, White Americans grew their wealth at the expense of Black people. That history continues to separate the Haves from the Have nots to this day.

Sadly, slavery is the first of many reasons Black people are centuries behind our White counterparts when it comes to wealth creation. And most of the other reasons are directly related to the systemic White supremacy that persisted in government fiscal policy during and after slavery. By using race to determine slave status, White Americans literally used race to distribute wealth and to determine economic class. They based their national economy on a system explicitly designed to block Black people from ever gaining access to wealth, let alone freedom.

Photo credit: Huffington Post

Photo credit: Huffington Post

Racist Housing & Social Welfare Policies: The Foundation of White Wealth & Black Poverty

The 1830 Removal Act “forcibly relocated Cherokee, Creeks and other eastern Indians to west of the Mississippi River to make room” for White people. Similarly, the 1862 Homesteading Act gave away millions of acres of Native American land to White people for free. According to Dr. Michael Oliver, co-author of Black Wealth/White Wealth:

“[The Homesteaders] came west, they settled in that land (of course it was the Indians land) and for settling in that land they got that property. That property formed the basis of wealth that was passed down from generation to generation. African Americans were locked out of that wealth building opportunity.”

When the Social Security Act was enacted in 1935, it was intentionally designed to “exclude two occupations agricultural workers and domestic servants, who were predominately African American, Mexican, and Asian.” Similarly, after World War II, the G.I. Bill and Federal Housing Authority (FHA) gave American soldiers and citizens access to federal loans and programs for home purchases, job training, education and other support services. However, racist implementation of these laws denied Black people from accessing the housing, education and resources these programs provided. As noted by Terrell Jermaine Starr in the New York Times:

“Black Americans…were specifically denied mortgages and many benefits of the G.I. Bill, among other opportunities that led to upward mobility. That [B]lack families still managed to thrive despite the decades of ghettoization that resulted from this exclusion – not to mention from segregation, violent discrimination and slavery – is a miracle.”

Photo credit: Atlanta Black Star

Photo credit: Atlanta Black Star

Dr. Oliver’s book further notes that: “African Americans either could not get loans from FHA or when they did get loans they were consigned to inner city neighborhoods.”

Which means average White families in the 1970s could “purchase a home in a suburban tract, that had no money down, that had an FHA loan, that cost less for mortgage, taxes and utilities than a comparable apartment in the inner city… Thirty years later they might have $250,000 in equity because that home has increased in value…”

During that same time period, countless Black families excluded from the FHA home buying program because of institutional racism, were forced to live in an urban community dwellings. As a result they lost access to the $250,000 in equity and other benefits that White families earned in the same time frame—just for being White.

Dr. Oliver further notes that we often forget that through racist interventions, “some people were born on third base. Other people have to start off at home and they have to hit a home run.”

When the Past Predicts the Future

This isn’t ancient history – we saw this pattern repeat itself in the mass predatory lending and racist distribution of subprime (i.e. toxic, harmful, junk) loan mortgages that led to the Great Recession of 2007-2010. According to the department of Housing and Urban Development, “In predominantly [B]lack neighborhoods, the high-cost [toxic loan] lending accounted for 51 percent of home loans in 1998 – compared with only 9 percent in predominately [W]hite areas.” As a result of these and other racist lending practices, Black communities lost more than half of their collective wealth – and are still feeling the fall-out.

Photo credit: Atlanta Black Star

Photo credit: Atlanta Black Star

Now, is racism the only reason for this peculiar interplay between debt and Black people in America? No. But if we are serious about needing to turn our collective economic condition around, we have to understand how we got to where we are today. Which means we need to be intimately familiar with how this history influences our collective financial reality.

When You Feel Ugly, You Act…

External factors are just part of the story behind Black economic disempowerment. The rest has more to do with choices made within our communities and how those choices are influenced by the legacy of racism. American consumerism prompts all of us to constantly “buy more and buy now.” However, author Tom Burrell (Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority) notes that “cues to incessantly buy resonate differently with a race that had to secure the right to be treated as humans and force white businesses to treat them like any other American consumer.”

Burrell writes:

“according to Demos, black groups— upper, middle, and lower— experience disproportionate rates of financial risk due to abundant credit-card debt and high-interest purchases of depreciating items, such as cars, electronics, and fancy appliances. Low-income blacks, however, are the dominant supporters of the multi billion-dollar payday loan and rent-to-own entities that can charge triple-digit interest rates, and rent merchandise at sometimes more than 200 percent above the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.”

In Almighty Debt, Dr. Malveaux noted that there is a certain psychology in the Black community around spending money that is directly related to our history. Burrell states: “Prevalent socio-economic conditions, combined with historic prejudices, have resulted in a case of low self-esteem, or low “race esteem,” that has affected our purchasing behavior.”

Dr. Joy DeGruy Leary’s seminal work Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome discusses this phenomenon in depth when she writes:

“I remember seeing a television show that featured the homes and cars of famous wealthy individuals. One young Black gentleman toured the audience through a sea of his “stuff,” …to elaborate about the fine details that made his possessions better than others. One of his stops was to show [off] his numerous cars, including his favorite, a mink-lined Bently…he was not even yet old enough to drive…People who believe themselves to have little worth, little power, little self-efficacy, will often do whatever they can to don the trappings of power…”

This type of spending is often called “conspicuous consumption.”

Photo credit: Cake Magic

Photo credit: Cake Magic

Conspicuous Consumption: Keeping Up with the Joneses

“Conspicuous consumption” as described in The Atlantic, argues that people tend to spend more money on visible goods in order to prove that they are prosperous. Conversely, the richer a society or peer group, the less important visible spending becomes.

So, when you are surrounded by poverty and a sense of cultural inferiority, your spending patterns tend to focus on obvious displays of wealth, like cars, clothes and jewelry. You know…bling. Thankfully, conspicuous consumption is more of a developmental phase than a final destination. As your collective group begins to improve financially, spending patterns typically shift to less obvious riches (i.e. concierge health care, expensive vacations, home renovations, personal coaches, etc.).

But so long as your collective group continues to be trapped by debt, poverty – and a low cultural self-image –wasteful, conspicuous spending rules the day. While this tends to be true across racial lines, the legacy of internalized inferiority make it stand out even more in Black American culture.

Kanye West noted this trend in his song All Falls Down:

“We buy our way out of jail, but we can’t buy freedom/We’ll buy a lot of clothes when we don’t really need em/Things we buy to cover up what’s inside/Cause they make us hate ourself and love they wealth.”

CLSJ’s Response to the Financial Crisis

In light of this history, the Center for Law and Social Justice is excited to announce our Black Wealth Matters: Building Financial Legacies workshop series this spring.

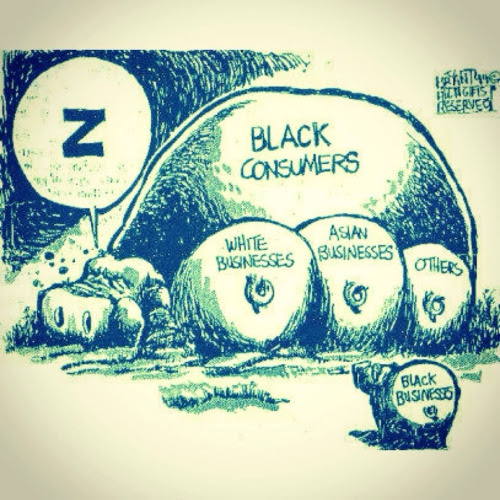

When Black employees go to work, they are typically employed by non-Black owned entities. When Black employees spend their money, it is typically spent with businesses owned by non-Black people. This matters more than we know.

This series will explore the state of personal finances; entrepreneurship and business development; collective wealth generation; and land ownership in the Black community. Each month, hear from experts who will help us understand how we arrived to our current financial position AND learn how we can improve our finances on an individual and collective level. See the flyer and details below for additional information.

On Friday January 20, 2017 we kick off our series with a deep dive into the state of personal finances. We’ll take a look at the following:

What is the current condition of personal finances in the Black community?

2. What are the historical and current conditions that preserve Black economic inequity?

3. What is a financial legacy and how can Black people create one for their families?

4. How can a community in financial distress strengthen its economic health?

5. How can cultural mindsets around Black people and money impact our financial future?

6. What steps can individuals take to strengthen their financial outlook?

Subsequent programs will focus on Black Entrepreneurship & Business Development (Feb. 10, 2017); Black Land Ownership (Mar. 24, 2017); Cooperative Economics (Apr. 21, 2017). Black communities need a new understanding about the power of our collective financial reality. Join CLSJ as we do our part to help make that happen.