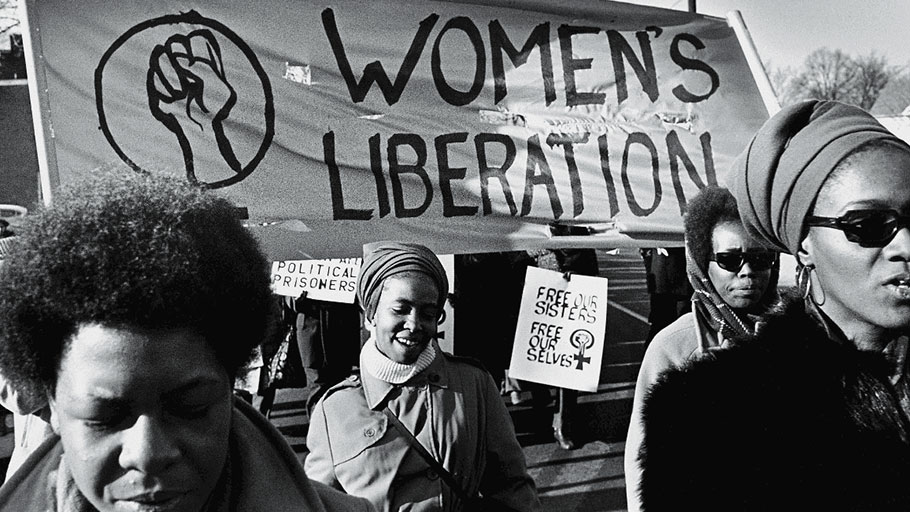

A group of women, under a “Women’s Liberation” banner, march in support of the Black Panther Party, New Haven, Connecticut, November 1969. (Photo: David Fenton / Getty Images)

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, Truthout —

Doug Jones in Alabama. Ralph Northam and Justin Fairfax in Virginia, Phil Murphy and Sheila Oliver in New Jersey: All Democratic wins made possible by Black women’s historical capacity for building organizational and structural power. This power — which was originally cultivated to protect and preserve Black bodies, to protect and preserve Black life — has commanded victories for the Democratic Party in 2017 and is poised to influence the midterms in 2018.

A timeline of current events centering white women would seem to light the path to these victories: Hillary Clinton’s defeat on November 8, 2016. Global resistance that demonstrated the will of pink-capped women on January 21, 2017. Alyssa Milano’s #MeToo tweet. But more than half of white women in Alabama, Virginia and New Jersey voted for the Republican, while Black women’s votes ushered in the Democratic winners at rates above 90 percent. It is Black women walking the path for the Democratic Party, yet the light continues to shine on white women who are on — or off — that road. Indeed, none of these current events centering white women make visible the African American women who paved the road in the first place: African American women like Mary Church Terrell, Frances E.W. Harper and Fannie Lou Hamer. Women who are the foremothers of #MeToo founder Tarana Burke. There are more, millions more. These millions are the Black women who strategized, founded and have maintained, for over a century, institutions that edify the Black community.

Informal networks maintained by enslaved African women kept Black people alive, literally and figuratively.

These institutions are civic, social, business and political. They are even athletic. They are diverse. They are Black Lives Matter and Zeta Phi Beta. They are Black Women’s Network and Mocha Moms, Inc. They are Black Women’s Health Imperative and National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. They are Black Girls Rock! and Black Girls Code. Girl Trek and Black Girls Run. They are The Links and they are everywhere. They are many, many more. They do not endorse candidates. They are not PACs. They do not lobby. They serve the community in various capacities and grow leadership in membership. And they are networks.

These networks often intersect, so that a woman who grew up in Jack & Jill and pledged AKA in college is also a Girl Friend. These organizations demand her time, as she has to serve on committee, has to roll up her sleeves and do the work. She beats a drum, online and off, to support the Movement for Black Lives. She is poised. When a crucial election comes up, she knows how to organize. Structures are already in place for her to do so.

She has been doing the work of delivering structural value to the Black community since her arrival on these shores. Black women have always been organized, despite the brutality of white system control. Informal networks maintained by enslaved African women kept Black people alive, literally and figuratively. Runaway and free-born Black women institutionalized these informal networks. In the North, organized groups of Black women aided runaways, pooled financial resources to help support small business enterprises and contributed to costs when members fell on hard times. The Colored Women’s Club Movement as a formal campaign was born out of this strategy employed by Black women in the North. Understanding the effectiveness of more formal structures to support African American communities and defend Black women from the sexual violence of dominant white men, Founding Mothers heeded the call sounded by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and organized colored women’s clubs under one structural umbrella at the 1896 First Annual Convention of the National Association of Afro-American Women.

In the early 20th century, Black college women founded sororities that have offered generations of educated Black women lifetime sisterhood and commitment to service in the community. Other organizations founded through the middle 20th century provided refuge from the racist exclusion of Black families that persisted in everyday American life. Now, in the 21st century, African American women continue to innovate, building bricks to edify a structural power that is already in place.

“These organizations and other community institutions like churches and colleges become entry points for candidates and campaigns to make contact with Black women voters,” L. Joy Williams, a political strategist and owner of LJW Community Strategies, told Truthout. “But more importantly, these institutions are how Black women organize themselves. Through these organizations, Black women volunteer and work in their communities and know first-hand what issues are important and the impact government policies and legislation have on the daily lives of their families and neighbors. It’s what makes them educated and reliable voters who are able to evaluate the records and values of candidates and make the choice that is best for their community.”

Williams is president of the Brooklyn NAACP and host and creator of #SundayCivics, a weekly show featuring African Americans who are actively engaged in our participatory democracy. Though #SundayCivics is separate and apart from the Brooklyn NAACP, Williams’s program is a dynamic complement to the work she does in that venerable 96-year-old branch of the civil rights institution Ida B. Wells helped found.

Higher Heights for America is another forward-looking organization rooted in the rich sustenance of Black women’s fortifying past. A pipeline for Black women’s political leadership nationwide, Higher Heights was founded in 2014 by Kimberly Peeler Allen and Glynda Carr. Carr, a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority and the NAACP, understood from her earliest childhood the importance of active civic engagement. This civic engagement is, for her, a matrilineal heritage. “In their lifetime, my great-grandmother — who died just shy of her 100th birthday — and grandmother were able to vote after years of fighting for this basic civic right,” Carr told Truthout. “Their experience shaped my family’s political activism. They saw voting as a way to improve their schools, economic situations and communities.”

Carr, who grew up in Connecticut, witnessed the power and responsibility of being politically active by observing the women in her own family. “My mother believed so strongly in the power of voting that on the day I turned 18, she drove me down to City Hall and had me register, and she called me every Election Day to remind me to cast my ballot,” she said.

Black women continue to interrogate the systemic racism and sexism that stagnate white progressives.

This family legacy of active civic engagement drives Carr’s commitment to support Black female political leadership through the organization she co-founded. “Higher Heights is a result of the examples set by the women who held sway over my life,” she said. “Their teachings, along with my own experiences, drive my work to increase Black women’s political involvement so we can have a place at the decision-makers’ table and are able to advance progressive public policies.”

Organizations like Higher Heights that were explicitly founded to engage the political process have a deeply rooted power that derives from the efforts of Black women through time. In 1969, Shirley Chisholm became the first and only Black woman elected to the US Congress, and in 1972, she became the first woman and the first African American to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. These firsts certainly suggest an aloneness, an absence of other women of color to support her trailblazing efforts; but, of course, that is not the case at all. Chisholm was a member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, and she remained in community even after her political career ended. She was, as just one example, a cofounder of African American Women for Reproductive Freedom, an organization whose list of founding members reads like a who’s who of late 20th century Black female leadership. Chisholm is one dynamic political force whose life’s trajectory inspired the Black female team that founded Higher Heights.

African American women trailblazers like Chisholm have historically utilized the formal and informal structural capacity of Black women to push a more progressive agenda in organizations dominated by white men. Consider the ways Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Jacobs energized the abolitionist movement. Where would the anti-slavery struggle have been without them — and the nameless, countless other Black women who, like these legends, did the hard work of freeing themselves? Just as Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” speech redirected white men’s proclivity toward gender and racial exclusion within the movement that was, ironically, organized to liberate enslaved people, Black women continue to interrogate the systemic racism and sexism that stagnate white progressives.

Carr said, “After working almost a decade in politics, in 2011, I found myself questioning why progressives had lost control of the US House and governorships. I was having coffee one day with Kimberly [Peeler Allen] at a Brooklyn café, mainly to talk about my next career moves, but the conversation shifted to our shared frustration that our political work most often found us in rooms with very few people of color, and especially very few Black women. Our experience told us that Black women are a key to long-term progressive leadership — and certainly, recent elections have proved this true. We knew that, like us, other Black women were seeking spaces and opportunities to aggregate and organize their political power and help move this country forward. That day, Kim and I began to sketch out what a political organization for and by Black women would look like, and we even came up with the name, Higher Heights.”

Carr says she and Peeler Allen spent the next two years doing research, having meetings and gathering with small groups of African American women to, as she explains, “talk about growing our political power and developing an organization to do this work.”

Young Black women voters in particular wanted to make a clear point that candidates need to intentionally engage us and not take us for granted.

By 2014, that work was happening. Higher Heights launched the #BlackWomenVote campaign in Georgia and Ohio, and launched the Higher Heights Sister-to-Sister Salon, where small groups of Black women gather for a series of discussions about critical issues affecting African American communities and the ways to increase political leadership to address them.

It is this level of Black female organization and structure that, in 2017, galvanized the Black women of an entire state — and drove from political power a vicious racist who was accused of child molestation by nine survivors. Carr said that while Doug Jones has acknowledged the critical role Black women played in his traditionally conservative state, “What’s less touted about this win is that our decisive voter turnout was a direct result of Higher Heights’s work to pen an open letter to the Democratic National Party demanding greater inclusion and support for Black women.”

The letter was signed by 30 Black women leaders, and it resulted in a convening with the Democratic National Committee some months before the Alabama election. “We demanded that the organization give Black women a return on our ongoing historic role in delivering progressive wins,” Carr said. Higher Heights’s demands also included investing in Black women voter programs in 2018 and hiring more Black women political strategists.

The Democratic Party would be wise to heed the strength of Black women. Carr says that the large percentages of Black women who voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 were mounting a key defensive strategy — their votes were “as much about keeping [Trump] out of the White House as it was about putting [Clinton] in it.”

However, Carr added, “We’re hardly a monolithic voting bloc. Post-election polling suggested that there were Black women who showed up at the polls and only voted for state and local candidates because they didn’t feel their interests were adequately represented and addressed by either presidential candidate. Young Black women voters in particular wanted to make a clear point that candidates need to intentionally engage us and not take us for granted.”

It is Black woman seeing and hearing other Black women, and not taking them for granted, that enables pre-existing structures to implement direct civic action. This is a point echoed by LaTosha Brown, co-founder with Chris Albright of the Alabama-based Black Voters Matter Fund. Brown says the work of Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party inspired her group’s own work.

“Our goal is to organize all Black voters in rural, suburban and urban communities around an agenda that advances our community, and not because it is tied to a particular candidate and/or party,” Brown told Truthout. “Our strategy is rooted in building Black power: We see that as creating the tools, mechanisms and vehicles to make sure that Black communities are self-determined and able to make decisions about the care, well-being and advancement of our communities.”

Brown is also a principal of TruthSpeaks Consulting, a senior adviser to Black Women’s Roundtable and a board member of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation. Born in New Jersey but raised in Alabama, Brown explains how Black Voters Matter worked to topple Roy Moore in her state’s historic race for the Senate. Black Voters Matter made sure to center Black voters in every stage of the campaign, empowering other local groups to organize. “We made sure that our message was rooted in affirming the power of the collective Black vote and focused on Black voters — not the candidates,” Brown said.

Brown estimates that over 90 percent of the leadership that the Black Voters Matter Fund works with is made up of Black women, and adds, “Our work is very much centered in a Black feminist social justice leadership frame.” Black Voters Matter partnered with Black sororities, women’s civic groups and social justice groups that focus on issues like reproductive health, criminal legal reform and immigration policy, and are led by African American women. These organizations galvanized the state’s African American voters in urban centers and rural areas. The list is long and includes Black Women’s Roundtable, Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice, Black Belt Deliberative Dialogue Group at Tuskegee University, Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice, Bama Kids and 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement.

The progressive work carried out by Black women in rural areas was crucial in voting efforts. Networking with local activists and community leaders in remote regions allowed Black Voters Matter to transport people to the polls.

“In rural communities, relationships are key to building successful [get out the vote] campaigns,” Brown said. “Most communities are [tight-knit] and very connected through church, family and work. Having the right people on the ground that are both respected and connected in these rural communities made the world of difference in our efforts.”

Many of the organizations Black Voters Matter worked with are overlooked by traditional political organizations. Brown continues to push back against the white, heteronormative, male power centered in the mainstream, insisting that now Senator Jones engage communities of color and the lesser-known organizations that represent them.

Higher Heights is also looking ahead, even as it builds on the foundation poured by Black women’s hands. Carr’s organization aims to build on the worker’s rights component of the mid-20th century civil rights movement, as Black women have the second-largest rate of labor union participation and are growing in leadership roles within unions. “Higher Heights is working to foster relationships with Black female union membership,” Carr said, “both in terms of engaging voters and identifying a pipeline of Black women leaders.”

Higher Heights is also focusing on greater representation of Black women in political office. According to Carr, the 21 Black women currently serving in Congress is a historic high, as are the numbers of Black women simultaneously serving as mayors of large cities. Higher Heights continues to work to grow the numbers of Black women in elected office through endorsements and grassroots support of candidates like Georgia’s Stacy Abrams, who is poised to become the nation’s first Black woman governor.

Carr insists that while Black women are set to influence the 2018 midterms, our power can be even stronger if we aggregate it, develop a clear agenda and maintain our commitment to civic action, like volunteering for campaigns, assisting “get out the vote” efforts and running for office ourselves.

Brown seems to agree. “I think we will have even more impact and influence in upcoming elections as more Black women seek public office and engage in organizing in their field.”

As we look ahead, the path forward is especially bright right now, despite the dim realities of the current administration. About 2018, Brown said, “I think this will be the year of the woman.”

Eisa Nefertari Ulen is author of the novel Crystelle Mourning, a novel described by The Washington Post as “a call for healing in the African-American community from generations of hurt and neglect.” She is the recipient of a Frederick Douglass Creative Arts Center Fellowship for Young African American Fiction Writers, a Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center Fellowship and a National Association of Black Journalists Award. Her essays exploring African-American culture have been widely anthologized, and her most recent essay, “Black Parenting Matters: Raising Children in a World of Police Terror” was published in the Truthout anthology, Who Do You Serve, Who Do Your Protect? Eisa has also contributed to Essence, The Washington Post, Ms., Health, Ebony, The Huffington Post, The Root, TheDefendersOnline.com, The Grio and CreativeNonfiction.org. She has taught at Hunter College and The Pratt Institute and is a founding member of RingShout: A Place for Black Literature. Contact her online: EisaUlen.com. Follow her on Twitter: @EisaUlen.