By Jelani Cobb

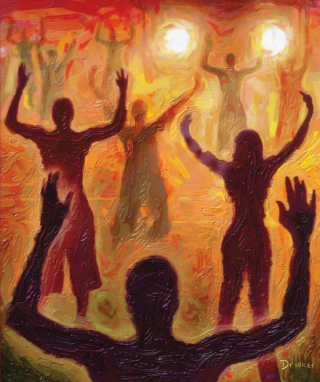

The New Yorker cover from the September 1, 2014, issue, by Eric Drooker. Credit Illustration by Eric Drooker

The New Yorker cover from the September 1, 2014, issue, by Eric Drooker. Credit Illustration by Eric Drooker

FERGUSON, Missouri—For a hundred and eight days, through the suffocating heat that turned the city into a kiln, through summer thunderstorms and the onset of an early winter, through bureaucratic callousness and the barbs of cynics who held that the effort was of no use and the prickly fear that they might be right, a community in Ferguson, Missouri, held vigil nightly, driven by the need to validate a simple principle: black lives matter. On November 24, 2014, we learned that they do indeed matter, just less than others—less than the prerogatives of those who wield power here, less than even the cynics may have suspected.

Last night, the streets of Ferguson were congested with smoke and anger and disillusionment and disbelief, and also with batons and the malevolent percussion of gunfire and the hundreds of uniformed men brought here to marshal and display force. Just after eight on Monday evening, after a rambling dissertation from the St. Louis County Prosecutor, Robert McCulloch, that placed blame for tensions on social media and the twenty-four-hour news cycle, and ended with the announcement that the police officer Darren Wilson would not be indicted for shooting Michael Brown six times, the crowd that gathered in front of the police headquarters, on South Florissant Road, began to swell. Their mood was sombre at first, but some other sentiment came to the fore, and their restraint came unmoored. A handful of men began chanting “Fuck the police!” in front of the line of officers in riot gear that had gathered in front of the headquarters. Gunshots, the first I heard that night, cut through the air, and a hundred people began drifting in the direction of the bullets. One man ripped down a small camera mounted on a telephone pole. A quarter mile away, the crowd encountered an empty police car and within moments it was aflame. A line of police officers in military fatigues and gas masks turned a corner and began moving north toward the police building. There were four hundred protesters and nearly that many police officers filling an American street, one side demanding justice, one side demanding order, both recognizing that neither of those things was in the offing that night.

What transpired in Ferguson last night was entirely predictable, widely anticipated, and, yet, seemingly inevitable. Late last week, Michael Brown, Sr., released a video pleading for calm, his forlorn eyes conveying exhaustion born of not only shouldering grief but also of insisting on civic calm in the wake of his son’s death. One of the Brown family’s attorneys, Anthony Gray, held a press conference making the same request, and announced that a team of citizen peacekeepers would be present at any subsequent protests. Ninety minutes later, the St. Louis mayor, Francis Slay, held a press conference in which he pledged that the police would show restraint in the event of protests following the grand-jury decision. He promised that tear gas and armored vehicles would not be deployed to manage protests. The two conferences bore a disturbing symmetry, an inversion of pre-fight hype in which each side deprecated about possible violence but expressed skepticism that the other side was capable of doing the same. It’s possible that, recognizing that violence was all but certain, both sides were seeking to deflect the charge that they had encouraged it. Others offered no such pretense. Days ahead of the announcement, local businesses began boarding up their doors and windows like a coastal town anticipating a hurricane. Missouri Governor Jay Nixon declared a preëmptive state of emergency a week before the grand jury concluded its work. His announcement was roughly akin to declaring it daytime at 3 A.M. because the sun will rise eventually.

From the outset, the great difficulty has been discerning whether the authorities are driven by malevolence or incompetence. The Ferguson police let Brown’s body lie in the street for four and a half hours, an act that either reflected callous disregard for him as a human being or an inability to manage the situation. The release of Darren Wilson’s name was paired with the release of a video purportedly showing Brown stealing a box of cigarillos from a convenience store, although Ferguson police chief Tom Jackson later admitted that Wilson was unaware of the incident when he confronted the young man. (McCulloch contradicted this in his statement on the non-indictment.) Last night, McCulloch made the inscrutable choice to announce the grand jury’s decision after darkness had fallen and the crowds had amassed in the streets, factors that many felt could only increase the risk of violence. Despite the sizable police presence, few officers were positioned on the stretch of West Florissant Avenue where Brown was killed. The result was that damage to the area around the police station was sporadic and short-lived, but Brown’s neighborhood burned. This was either bad strategy or further confirmation of the unimportance of that community in the eyes of Ferguson’s authorities.

The pleas of Michael Brown’s father and Brown’s mother, Lesley McSpadden, were ultimately incapable of containing the violence that erupted last night, because in so many ways what happened here extended beyond their son. His death was a punctuation to a long, profane sentence, one which has insulted a great many, and with damning frequency of late. In his statement after the decision was announced, President Barack Obama took pains to point out that “there is never an excuse for violence.” The man who once told us that there was no black America or white America but only the United States of America has become a President whose statements on unpunished racial injustices are a genre unto themselves. Perhaps it only seems contradictory that the deaths of Oscar Grant and Trayvon Martin, John Ford and Michael Brown—all unarmed black men shot by men who faced no official sanction for their actions—came during the first black Presidency. Or perhaps the message here is that American democracy has reached the limits of its elasticity—that the symbolic empowerment of individuals, while the great many remain citizen-outsiders, is the best that we can hope for. The air last night, thick with smoke and gunfire, suggested something damning of the President.