By Keith L. Alexander —

This article was originally published by The Washington Post in December of 2017

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Blocks away from Harvard Law School, renowned civil rights attorney and law professor Charles J. Ogletree Jr. was at home with family, readying himself for a celebration in his honor.

As his wife, children and grandchildren rushed around picking out outfits and fixing their hair that October day, Ogletree gave a visitor a tour of his home. He showed off photos of his family and some of him with two of his best-known former students, President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama.

Then he pointed out one of himself with Nelson Mandela, smiling as he recalled their years-long friendship after Mandela’s release from prison. But in a flash of the disease that has begun to rob his memory, Ogletree spoke about the deceased South African leader as though he were still alive.

“Now that he is here, he won’t leave,” Ogletree said. “I see him every year.”

In his decades-long career, Ogletree’s mind has been his weapon in legal cases that took him from D.C. Superior Court to the U.S. Supreme Court. He represented Anita Hill when she made her 1991 sexual harassment claims against then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. And he was a longtime moderator of a 1990s PBS series on ethics, where he challenged some of the nation’s top business and political leaders in debate.

Now Ogletree’s mind is battling him. Four years ago, when he was 60, family and colleagues noticed he had begun stumbling over names and repeating stories. The following year, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a disease that usually ensnares victims 65 and older.

“We initially felt hopeless,” said Ogletree’s wife, Pam. “But we have faith and we believe in prayer.”

Ogletree, sitting next to her, is optimistic.

“This disease hasn’t done nothing. It doesn’t bother me,” he said with a large smile.

Building a career

In the fall of 2013, Ogletree’s daughter, Rashida Ogletree-George, noticed her father asked her the same question a few times. “What are you doing for Thanksgiving?” he’d say, then await her response.

The family talked among themselves. At first, they chalked up the lapses to Ogletree’s exhaustion from a hectic travel schedule.

But things got worse. Ogletree-George, a lawyer in the Justice Department’s civil rights division, recalled how her father would forget where the bathroom was in her home, even though he visited often.

“We were all worried,” Ogletree-George said. “We’re so used to someone who always remembered everything.”

During his career as a litigator, educator and author, Ogletree became known for his uncanny ability to remember facts, dates and case law.

He grew up in the segregated farming town of Merced, Calif., where his father worked as a farmer and his mother was an aide at a junior college. He was the first in his family to attend college when he was accepted into Stanford University, where he met his future wife.

Charles J. Ogletree poses with current and former D.C. Public Defender Service employees. (Katye Martens Brier for The Washington Post)

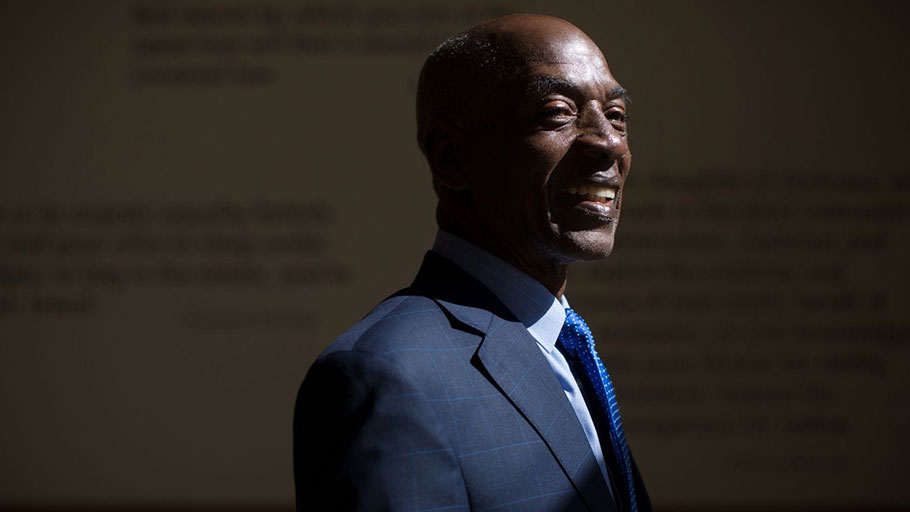

Charles J. Ogletree reacts to crowd applause during a celebratory symposium honoring the Harvard law professor. (Katye Martens Brier for The Washington Post)

As a student, Ogletree became interested in criminal law while attending the 1972 trial of Black Panther party member Angela Davis. He went on to Harvard Law School, then took a job as a public defender in the District. There, he quickly developed a reputation as someone who worked long hours preparing cases. Colleagues, impressed by his steadiness, gave him a nickname that stuck: “Tree.”

Washington judges still remember Ogletree’s deep knowledge of the law. “He was always somebody you wanted to come into your courtroom with a case because you knew it would be well tried,” said D.C. Superior Court Judge Frederick H. Weisberg. “He was respected by everybody, judges and prosecutors alike. There aren’t that many people of whom that could be said.”

Wesley A. Oliver was in his 20s and facing pimping charges when he met Ogletree decades ago. Oliver said he’d had other public defenders represent him, but never got the attention Ogletree gave him. Together, they scoured the District streets late at night for evidence and witnesses to strengthen his case.

“He was very attentive and made me feel like I had one of the highest-priced lawyers around,” said Oliver, 63, who owns a construction company in Connecticut. “That man really fought for my case.” After days of testimony, a jury found Oliver not guilty of all charges.

Ogletree left the public defender’s office in 1985 after he was passed over as director and returned to Cambridge as a law professor at his alma mater. He focused on using the courts to fight against racial injustice.

In a 1990 case before the Supreme Court, Ogletree won a new trial for a black man accused of murder in Georgia, showing that prosecutors had excluded African Americans from the jury.

In 2003, he took on one of his more challenging cases, representing about 100 survivors of the 1921 race riots in Tulsa, where white residents attacked hundreds of black residents and set fire to their homes and businesses.

Ogletree, along with attorney Johnnie Cochran, brought a lawsuit against Tulsa and Oklahoma, arguing the survivors deserved financial restitution.

The courts eventually sided against them, saying too much time had passed since the riots. But it was a cause worth fighting for, those close to Ogletree said.

“He knew it would be difficult, but he wanted to give their voice a fight,” Pam Ogletree said. “That’s who he is.”

‘Already a legend’

As the family caravaned to Harvard, Pam Ogletree tugged her husband’s Martha’s Vineyard baseball cap off his head and looked him over. He had lost more than 70 pounds since his diagnosis, leaving even his newer suits slightly oversized.

“Papa,” she said, using the family nickname, “you did a wonderful job getting ready. But let’s just fix your tie a little.” She asked their son, Charles III, an accountant who had flown in from Tallahassee, to straighten it.

When the Ogletrees were ushered into Harvard’s Wasserstein Hall, more than 500 people stood and applauded. Ogletree smiled broadly and waved at guests including Hill, the current and former deans of Harvard Law School, and former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick. Former colleagues and students filled the room.

Charles J. Ogletree greets guests following a celebratory symposium honoring the Harvard law professor at Wasserstein Hall on the Harvard Law School campus. (Katye Martens Brier for The Washington Post)

Ogletree walked toward the podium where there was a microphone waiting. But his wife steered him to the front row to sit with his family.

His Alzheimer’s was no secret here. Ogletree revealed his diagnosis to Harvard faculty and students last year.

For nearly three hours, the program seemed a combination of a tribute and retirement program, even a bit of a memorial. Some people wiped away tears.

Avis Buchanan, the D.C. Public Defender Service director, was a Harvard law student when Ogletree recruited her to join the office.

“He knew you every time he saw you, and made you feel like he knew you and made you feel like he would do anything for you,” she said. “And in fact, he would do anything for you, despite all the other demands on his time.”

Ronald C. Machen Jr., the former U.S. attorney for the District, sat among other former prosecutors. Ogletree was one of his law professors.

When Obama was elected president, Machen said, Ogletree called to urge him to apply for the U.S. attorney position. “Every move I made, he has played a tremendous role in my decision-making,” Machen said. “He is one of my biggest mentors.”

Hill told the crowd how, as she was preparing to testify in front of the Senate in 1991 about allegations of sexual harassment against Thomas, her former boss at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a friend suggested she hire a good criminal attorney.

She remembered Ogletree from the 1980s when the two of them worked in the District, she as a staff attorney with the EEOC and he as a public defender blocks away.

“Among the young lawyers in D.C., he was already a legend. He was a gifted defense attorney and passionate criminal justice advocate,” she said.

It was Ogletree’s idea, Hill said, to hold an impromptu news conference announcing she had passed a lie-detector test.

“He was the smartest and baddest man in the room,” she said as the audience laughed.

Back home after the program, Ogletree chuckled at Hill’s assessment. “That’s true,” he said. “And I still am.”

Fighting Alzheimer’s

The disease has robbed Ogletree of a great deal of his independence. He hasn’t driven in over a year, when a minor accident left a door of his Nissan Rogue with dents and scratches. Soon after, he stopped teaching and went on long-term disability. His wife said he no longer meets with clients.

Ogletree’s family has no history of Alzheimer’s, his wife said. But African Americans ages 65 and older develop the disease at a higher rate than any other ethnic group, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Researchers also have found that people with diabetes or a history of high blood pressure have a greater risk of Alzheimer’s. Ogletree has both.

The Ogletrees have changed his diet so he eats low-sodium foods, no pork and lots of coconut milk, which has been shown to improve brain health. Each day, he takes 35 pills and vitamins. And the couple walk three miles every morning. They have seen some benefits; his blood pressure has improved.

Ogletree still serves as a role model to many, including the former president.

“Charles has always been more than a mentor to me and Michelle; he’s been a wonderful friend and generous presence in our lives. We love him and Pamela dearly, and we’re so proud of the way they’re choosing to live with Alzheimer’s — to continue teaching and inspiring others the same way they’ve taught and inspired us,” Obama said in a statement.

Pam Ogletree watches her husband closely, trying to guard his words and tapping his leg if she thinks he’s about to say something out of character for him. Alzheimer’s has altered her husband’s “judgment” she said, causing him to make statements he would not normally make. “Sometimes he says things that are totally counter to what he believes and has spent his life championing,” she said.

“There are times he is lost, then he says or does something that gives me a glimpse of who he was,” she said. “We can and will alter the course of this illness.”

Ogletree chimed in. “Yes, we will.”

Magda Jean-Louis contributed to this report.