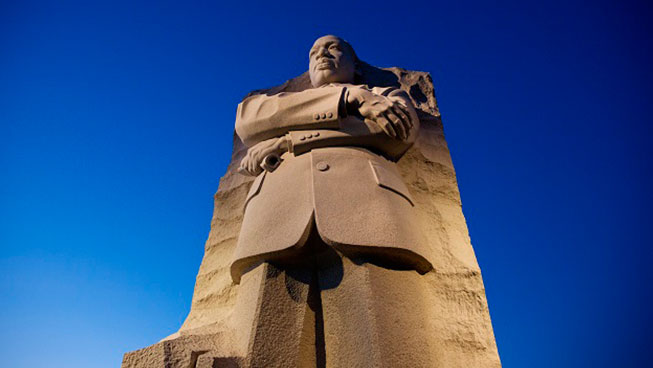

Narratives describing the historic victories for voting rights obscure the ultimate reality. What few gains the civil rights movement did secure, unfortunately, on the most part did not survive. (Photo: PBS News Hour / Flickr)

By Shahid Buttar, Truthout

The newest Smithsonian museum in Washington, DC — the National Museum of African American History and Culture — rightfully focuses on the horrors of slavery. It misleads visitors, however, by overstating the extent to which our nation has recovered from the enduring legacy of slavery and segregation.

These days, with a monument honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. standing near the National Mall in the nation’s capital, and a national holiday dedicated to his memory, many official narratives take racial integration for granted, even as a longstanding civil rights crisis continues. A closer look at the repression faced by civil rights organizers and the subsequent slow eroding of the civil rights movement’s historic victories reveals that this country’s stated commitment to equality is, at best, a veneer.

Repression Faced by Civil Rights Organizers

Many of the civil rights movement’s most visionary goals never came to fruition, due in large part to the intense state suppression it faced, the vicious and calculated assassination of its leaders, and the daily brutality of police and vigilantes reacting with violence to the desegregation of public spaces and institutions.

In addition to state and vigilante violence that aimed to suppress the civil rights movement, other forces also emerged to stymie its goals. In his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King particularly bemoaned the obstacles presented by moderate liberals whose tacit support for the establishment lent it the power to disregard majoritarian preferences for equality.

Ultimately, the civil rights movement was denied its most visionary goals by a policy establishment unwilling to grant them.

Civil rights leaders had hoped to secure a right to employment, food, housing, education and health care — all of which were goals that Dr. King explicitly referenced. Among its various goals, desegregation and voting rights were the only two ultimately secured in law and policy.

What Happened to Voting Rights

The two victories that the civil rights movement did secure have withered in the decades since then. Voting rights, for example, have dramatically eroded from their high-water mark.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which was expanded and renewed in 1970, 1975 and 1982) outlawed racial discrimination in public institutions as well as businesses; desegregated public schools; and began the consolidation of voting rights continued by Congress in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Meanwhile, a series of Supreme Court rulings historically expanded voting rights.

Just four days before the Senate’s historic 1964 vote ending a filibuster by southern Senators that had lasted for over two months, the Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims that electoral districts for state House and Senate elections must include equal populations, establishing the “one person, one vote” rule by forcing states to grant urban areas representation commensurate with their population. Two years later, the Court prohibited poll taxes in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) eventually grew widely supported across the political spectrum. Under the Bush administration, in 2006, when the Senate was controlled by Republicans whose party opposed voting rights in other forums, the chamber passed a bill to reauthorize the VRA’s provisions by a unanimous vote.

At the time, Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-Wisconsin) said, “The Voting Rights Act is vital to America’s commitment to never again permit racial prejudices in the electoral process.” Then House Majority Leader John Boehner (R-Ohio) described the VRA as “an effective tool in protecting a right that is fundamental to our democracy.”

Seven years later, in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down one of the VRA’s most critical provisions as unconstitutional in Shelby County v. Holder.

Section 5 of the VRA mandated preclearance provisions that forced states with a history of discrimination to preclear proposed changes to voting laws with the US Department of Justice (DOJ) before they were allowed to go into effect, in order to ensure that they did not discriminate against racial minorities.

To determine the jurisdictions over which the DOJ could assert its formidable Section 5 powers, lawyers turned to Section 4, which specified the coverage formula approved by Congress. Having been last updated in 1975, however, the formula’s age proved to be the Act’s undoing: The Supreme Court reversed both the district court and the appellate ruling that had affirmed it. The five most conservative Justices (Roberts, Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas and Alito) ruled that Section 4 unconstitutionally differentiated among jurisdictions “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.”

Without Section 5, incumbents can make changes to voting laws, intentionally skew elections and then suffer any potential consequences after the fact — when court victories are meaningless.

Predictably, over a dozen states assaulted voting rights in the wake of the Shelby decision. Although courts in several jurisdictions did intervene before the 2016 election, those new rules suppressing voters could alone account for the result of the 2016 presidential race. It was the first in 40 years conducted without the VRA’s full protections.

But even before the Shelby case, voting rights had been largely eviscerated, reduced to a shadow of the civil rights movement’s goal of securing rights to fair and equal representation. The right to merely cast a ballot in no way correlates to fair representation, which the Supreme Court has affirmatively rejected as a component of voting rights.

The Voting Rights Act itself may have unfortunately reinforced the problem, by presuming “a majoritarian winner take all voting system.” The VRA was limited to “traditional methods of improving the continued underrepresentation of racial minorities,” stopping far short of structural reforms that would make elections more representative generally, including but also extending beyond race.

Some proposals would remove single-member districts and instead allocate representation (for instance, in a state’s congressional delegation) according to a party’s share of the vote. Others would remedy the winner-take-all character of state delegations to the Electoral College, which could have been forced to elect a different president in 2016 had Democrats sought constitutional rulings to impose reasonable, straightforward voting rules far less contorted than those contrived by conservatives in Bush v. Gore.

The voting rights jurisprudence that nods toward equality relies on subjective tests to distinguish between permissibly drawn congressional districts and those that are unconstitutionally drawn. But beyond the discrete controversy in any gerrymandering challenge, the majority-minority districts created within the VRA’s limited context to ensure political representation for racial minorities may ultimately suppress the extent of their representation.

Narratives describing the historic victories for voting rights obscure the ultimate reality. What few gains the civil rights movement did secure, unfortunately, on the most part did not survive.

What Happened to Desegregation

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), the Supreme Court rejected de facto housing discrimination as a justification for unequal educational opportunities. More than 60 years ago, the Court recognized that “segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws,” and required interdistrict busing between school districts to ensure racial integration.

Fifty-seven years later, the Court effectively reversed itself.

In 2007, two new justices (Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito) joined the Supreme Court, having been appointed by a president whose own legitimacy was suspect. One of the first decisions in which they participated effectively overturned Brown, without claiming to do so.

The 2007 Parents Involved decision prohibited public school districts from pursuing voluntary intradistrict busing plans to prevent racial isolation — prohibiting essentially what Brown had historically mandated. While perversely citing Brown, the Roberts Court eviscerated its holding and left Brown a doctrinally dangling shadow of its former self. As Justice Stevens wrote in his dissent from the majority decision, “The chief justice’s reliance on our decision in Brown,” entails “a cruel irony.”

Today, de facto segregation in the housing market routinely determines which public schools students have an opportunity to attend. It also drives the experiences of young people with respect to police, who are deployed across the US, particularly in low-income communities of color, and who behave very differently in those settings than when policing high-income areas or examining white suspects.

De facto segregation in the housing market, and where any given individual might happen to reside, effectively determines the extent of their rights vis-à-vis police. In affluent suburban areas, or perhaps when interacting with residents who they do not perceive as a threat, police engage in significantly less violence against civilians.

In these tranquil settings, police rarely approach suspects chosen effectively at random to aggressively seek their consent to be searched, as many people of color who have lived in major cities have experienced. In low-income communities, police often presume criminality rather than innocence despite our constitutional commitment to due process.

The historical over-deployment of police in low-income neighborhoods, as well as the enduring legacy of compounding biases at every stage of the criminal legal process, together create a further problem. On the one hand, proponents of data-driven policing claim that objective measures and predictive tools can diminish systemic bias.

Yet any predictive algorithm — whether used to determine how police allocate their forces across a city, or what level of bail an accused defendant must post in order to be released form pretrial custody — is based on data from prior examples. And because prior data from the criminal legal system is undeniably ridden by biases, the results generated by predictive algorithms will be, too.

That is to say, not only have our nation’s housing markets grown once again increasingly segregated, but the social stratification driven by that segregation may be growing more severe. It is also growing insulated from critique due to the legitimacy lent by seemingly objective technology that in fact promotes profound biases. Put directly, predictive policing can entrench and perpetuate discriminatory force allocation, as well as longstanding sentencing bias.

While public institutions have grown increasingly racially integrated across the US, the historic triumphs of the civil rights movement have eroded. The movement sought a broad-based agenda, from which it secured only two particular goals. Both of those victories have withered, as the rights we continue to celebrate have been reduced to vestiges.

This was no accident. The history of the movement’s suppression and “neutralization” by government intelligence agencies is crucial to consider, especially as we anticipate what further abuses to expect under the Trump administration.

Shahid Buttar is a constitutional lawyer, DJ, MC, electronic musician, director of grassroots advocacy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and former executive director of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee.