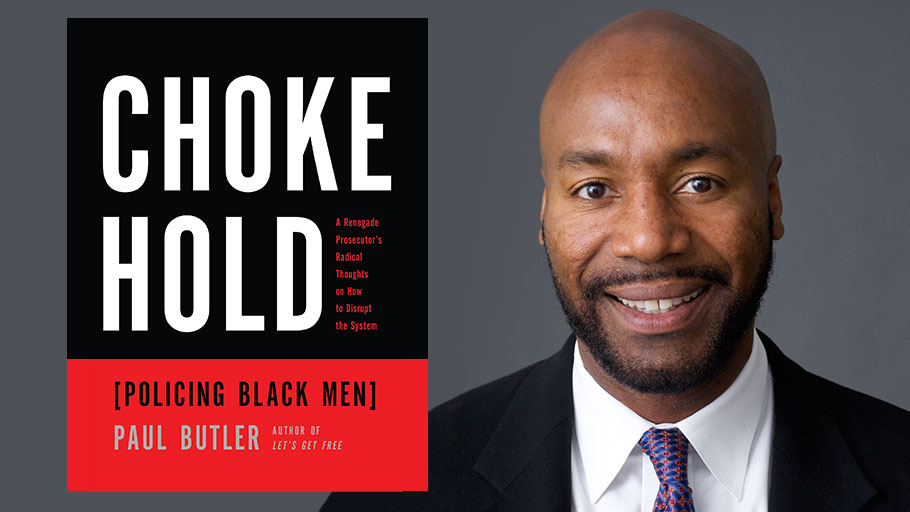

Paul Butler talks about breaking the “chokehold” on African American men

By Sam Fullwood III

Early on, in his recently published book, Chokehold [Policing Black Men], Paul Butler states, “[c]ops routinely hurt and humiliate black people because that is what they are paid to do.”

It’s a bold and stark claim that Butler, a Georgetown University Law School professor and former federal prosecutor, never backs away from as he challenges social activists to confront the nation’s broken criminal justice system.

To cite one of many examples drawn from the recent, sensational headlines of police abuses of black men, Butler notes that Ferguson, Missouri — site of sustained protests following the 2014 police killing of unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown — had more criminal offenses (32,975) than citizens (21,000 in 2013). The overwhelming majority of those arrested were black men. In fact, African Americans comprised 94 percent of arrests for “failure to comply,” 92 percent for “resisting arrest,” 92 percent for “disturbing the peace,” and 89 percent for “failure to obey,” according to Butler.

“Ferguson is America,” he writes.

During a conversation this week with ThinkProgress, Butler explained his personal experiences as a black man in America, his anger at the oppressive nature of white supremacy embedded in U.S. law, his passion for hip hop, and his optimism that future generations will benefit from the nascent movement for black lives all inspired him to write the book.

Chokehold? That’s a provocative title. Tell me about how you came up with it.

I was referring to the literal chokehold that the New York Police Department put Eric Garner in [in July 2014]. Garner was arrested for the crime of selling a single tobacco cigarette on the street. It’s crazy that people could go to jail for that, and Garner had said, ‘Not this day, officer. Could you please not arrest me this day.’ The officer perceived that Mr. Garner was resisting arrest so he put him in a chokehold, which is illegal under NYPD regulations. And Mr. Garner said ‘I can’t breathe’ 13 times and he died right there on the street.

The police have you in this grip, trying to get you to comply but you cannot comply because you can’t breathe, because of the vice grip. In some ways, that seemed emblematic of the black male experience in the United States. We have a chokehold on us.

In the context of criminal justice, there are two steps: The first is the construction of every black man as the thug. The second is this set of law and policy and social practices that respond to the thug. So in the book I reveal all this amazing social science that tells us that when people see black men, they respond differently than when they see other people. A lot of it is implicit. It is unconscious. Black men cause a lot of fear and anxiety. We make people nervous.

If it’s just people not wanting to sit next to me on Amtrak, fine. I prefer having two seats to myself. But when it’s police being more likely to shoot you, that’s a real problem.

“That seemed emblematic of the black male experience in the United States. We have a chokehold on us.”

The writing in the book is really provocative. Did you intend it to be?

I did. When we look at the way that brothers are dealt with in our justice system, I had to be provocative. I had to be angry and I had to come up with some constructive, lasting solutions for transformation.

You know, when you look at African American history, one of the questions you have is: when you see what black people have gone through, why do we remain so patient? Why do we remain so patriotic? I’m not sure what the answer to that question is. But I know that the one thing that sets black people off like nothing else is feeling targeted by the police.

The times that black people have abandoned peaceful protest and taken into the streets and burned down buildings and have thrown rocks; every time there’s been a major civil insurrection it’s been because of something the police have done. It’s like African Americans are expressing we can patiently endure segregated schools and poisoned water, but we will not take being the victims of violence by the very people who are supposed to protect us.

Why is that?

I just think there’s something visceral about feeling targeted for a beatdown by your own government. You know if we look at what happened in Flint, Michigan, to a lot of people that seemed complicated; it seems unintentional, it seems tragic. But when we look at what police do to black people from stop-and-frisk, where they put their hands all over the bodies of mainly young black men, to unarmed African Americans being more likely to be killed by police, it’s literally a matter of life and death. There’s this entrenched notion of African Americans having to defend ourselves from the government that we pay taxes and rely on for our security.

The book is personal in some ways and academic in others. You mix the law and hip hop. Who’s the audience for that?

The audience is for people who are trying to understand this racial crisis that we find ourselves in in the age of Trump. We’re post-Obama. We’ve had the first African American president and yet the conversation about race seem more fraught than ever. So what Chokehold is about is constructive solutions to move us forward in terms of racial justice and in terms of having our democracy work better for all of our citizens.

And, finally, I’m hoping to help this crucial, new movement for black lives strategize, harness this great spirit of resistance into some practical applications for change.

You write, at one point in this book, that you enjoyed locking up black men?

You know, I had been in a totally segregated, beautiful community on the South Side of Chicago, where I had virtually no interactions with white people until I went to an integrated Catholic high school. Then, I got a great education at Yale and then Harvard Law School. But something happened to me in those [white] spaces. I lost my identity in a sense. I became like the brother who Toni Morrison describes as having lost his ancient properties.

When I came to D.C. and worked as a prosecutor for a time in the Superior Court. I hadn’t seen that many black people since the South Side of Chicago. The cool thing was that black people were present in everything, at every level, from the judges to the prosecutors to the defense attorneys to the courthouse workers to the police officers.

I would love to stand up in front of jurors, who were these elderly black people who had moved to D.C. from North Carolina and South Carolina in the 50s. They were expecting that the defendant was going to be black and they were right. But what they hadn’t expected to see was this tall, young black guy representing the government. These old black people would beam at me as if to say ‘You go, boy. You represent the United States.’

I loved the work. I loved proving, demonstrating, showing off for the jurors that yeah, there was this bad guy and then there was me. In some ways, that was what I was hired to do. I was hired to be a black prosecutor and I was good at performing both those aspects of my job description.

And then it changed?

Because of an intellectual journey and because of a beatdown by the police. The intellectual piece was during the time I did this work in D.C., I wondered, what is going on? If you would go to Superior Court in D.C., you would think that white people don’t commit crimes. They are just not there as defendants.

So part of it was being concerned about the way my black body was being used to justify what was going on with all of these young brothers and sisters. I didn’t go to Harvard Law School to put black people in prison.

“I didn’t go to Harvard Law School to put black people in prison.”

Then, the beatdown was what I talk about in my first book, Let’s Get Free, being arrested and prosecuted for a crime I didn’t commit, and having things work out very well for me. They worked out because I had the resources to hire the best lawyer in the city… and I could afford to hire her to represent me and that’s the main reason why things worked out well fine. Other reasons were I had legal skills. I had literally prosecuted people in the courtroom where I was being prosecuted. I had social standing and we made sure the jury knew I was a prosecutor who had gone to these elite schools. I had these well-known folks come be my character witnesses.

The final reason things worked out well for me is because I was innocent. But when I thought about it, that didn’t seem like nearly the most important reason.

I just thought I couldn’t do this work any more, in part because a lot of things that happened to me were things that defendants in my cases had said all the time, including that the police had lied.

Well, in my case the officer got on the stand and lied his face off. I have no idea why he did that but my great lawyer was able to expose his lies. Defense attorneys say to me now, it shouldn’t have taken that experience for you to know that’s what happens every day. That police unfortunately lie and that the system is really set up against the accused person, who is most often a black man.

The fourth chapter of your book is probably the most controversial because you talk about the high rate of crimes that black men commit. You write that some black men asked you not to include that chapter. Why did you?

I think in some ways the problem of black male violence and the problem of police violence against black men are related. You really can’t have one conversation without the other. I get the concern of some people that if I start taking about black male violence, it sounds like I was being persuaded by those silly kinds of arguments by right wingers.

The idea is not to cede this important conversation to the right, but to have all of these great new solutions championed by the people who have the best interests of our people at heart.

You suggest reforms. You call it Abolition: the Third Gift. What is the ‘third gift’ and can you reasonably expect it to come about?

Chokehold is about ways to disrupt the system to create the transformation that we need. There are two things we can do right now: have half of police officers be women and to require college degrees of cops. Both of those are proven, evidence-based ways of having officers who are more like guardians and less like warriors. Female cops and college-educated cops are much less like to use force and they’re just as good cops, working out situations that don’t involve locking people up.

When I look at earlier struggles for black liberation and racial justice, they’ve always been about abolition. The first [gift] was about the abolition of slavery. The second [gift] civil rights movement was about the abolition of old Jim Crow. And I think this new movement is about the abolition of the new Jim Crow. The movement for black lives has targeted prisons and said we need to think about prison abolition.

One of the important things to understand about prison abolition is that it’s a gradual decarceration. I don’t know anyone who thinks that we should just go unlock every prison door tomorrow. What people [ought to] understand is that we need to do this in a thoughtful way that will take a long time.

Forty percent of people who are locked up could be let go tomorrow with no consequences for public safety. These are older people who have been locked up for a long time. These are non-violent folks. So let’s start with them. We lock up people for so much longer than anywhere else in the world that some prisons are now literally operating assisted living facilities for elderly people who can’t get by day to day, so clearly these are people we don’t need to be spending all this money to incarcerate.

“I think this new movement is about the abolition of the new Jim Crow.”

At the end of the book, it sounds like you’re calling for violence to end over-policing. Is that an accurate view?

Not at all. One of the things I’m interested in Chokehold is how to transform the system. When I look at ways that activists have thought about racial justice, I see three avenues that people talk about a lot. One is law; one is violence; and one is capitalism.

Law has been the traditional approach. Civil rights. In some ways that was a great success. In other ways, unfortunately, that movement was a failure. If you are the average black kid, who has to go to a public school, you’re no better off in 2017 than you were in 1954. You’re almost as likely to attend a segregated school and you’re probably getting a worse education now than little Miss Brown would have gotten in her school in the 1950s. In that way, civil rights hasn’t brought us all that we hoped it would.

Some other activists have thought about capitalism. This is an enduring theme in black political discourse, that the way to move ahead in the United States is to make money, to own businesses. The idea is that having money is a way to insulate yourself from the ravages of white supremacy. You know, I’m interested in hip hop and that’s a very common theme in hip hop and black popular culture.

The other common theme, not only in black culture but in American culture, is violence. Frederick Douglass said ‘power concedes nothing without a struggle’ and if we look at the first abolition, the abolition of slavery, that was accomplished with the most violent war in American history.

What about instances of violence in this new movement? If you look at when police are charged, it’s when folks have taken it to the streets. So violence can be productive, but does that make it right? In Chokehold, I say no for two reasons: No human being should be targeted for violence to make a political point because number one, that’s immoral, and number two, on a programmatic level, it wouldn’t work. African Americans are 13 percent of the population. If we resorted to violence as a political end, we would be crushed.

Violence is a form of lawbreaking that I discourage. There are other forms of lawbreaking that are a part of resistance movement. Again, these aren’t things that everyone is going to be willing to do. That’s why I entitled that section ‘For Runaway Slaves.’

Chokehold has a plan of action, a strategy, projects for two different kinds of activists. One are for folks like my law students, who want to create change but want to hold down their respectable jobs and who aren’t interested in being arrested and putting their bodies on the line. Not every slave would have run away. Not every black person, back in the day, would have led a slave insurrection. Some folks would, so Chokehold has some suggestions and ideas and aspirations for those folks as well.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.