By Paula Orlando

Staggering statistics of violence in Brazil continue to make headlines in the country and abroad, but the invisibility of the victims and indifference toward them blunt the impact of the numbers. According to the 2014 Map of Violence published by FLACSO-Brazil sociologist Julio Jacobo Waiselfisz, 30,000 people between the ages of 15 and 29 – 77 percent of whom are black – are murdered in Brazil every year. Additionally, the annual report of the widely respected Brazilian Public Security Forum indicates that in 2008-2013 the police killed at a rate of six people per day, while a research group at the Federal University of Sao Carlos (UFSCAR) found recently that 61 percent of those killed by the police in Sao Paolo State are black. The absence of popular outrage over these facts is being addressed by a range of initiatives, and social media – of which Brazilians are avid users – are an important tool to this end.

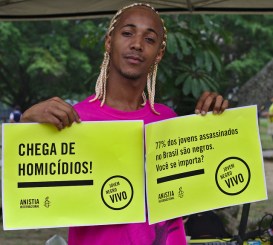

- Amnesty International’s newly launched campaign, Jovem Negro Vivo, uses social media to raise consciousness about the rates of violence and societal responses to it. One of the main parts of the campaign is a video showing a black teen traveling through his neighborhood and city, successively encountering other invisible people. At the end, the teen faces a similar fate – death and invisibility. The campaign questions the trivialization of violent deaths and society’s silence about it. The campaign asks: “84 homicides per day. Do you care?” And adds: “More shocking than this reality, just indifference.”

- Rede Jovem, an internationally acclaimed NGO created in 2000, is conducting Projeto Wikimapa with collaborative technologies to identify neighborhoods, streets and services in communities that are invisible – that is, not shown on official maps – even though many are heavily populated. A number of local projects are redrawing the maps of various cities, including Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo. The resulting maps, which can be accessed on the Web and handheld devices, expose communities’ rich social structures to the world. Some of this work is presented in a new released documentary, Todo mapa tem um discurso – “Every map has a discourse.”

In a society in which significant numbers of communities and individuals are still invisible to the state and fellow citizens, violence is not surprising. During the recent and run-off campaigns Dilma Rousseff met with grassroots leaders who demanded urgent action to end systematic violence against poor youth and police abuse. She promised them that she would push further implementation of specific youth programs such as Juventude Viva, while also recognizing the need to continue confronting racism and start taking serious measures against police abuse. Human rights organizations and community activists have pledged to hold her to her word. Communication and technology tools – which activists used during protests last year to gather evidence of police abuse through crowdsourcing – can provide a boost to citizens and activists in reclaiming public spaces and demanding better social services. Creating inclusive and participatory maps, for example, facilitates postal service, the allocation of resources, and the implementation of programs such as cultural and after-school activities that help protect vulnerable youth. Further, the use of collaborative media technologies has the potential – over time – to reduce invisibility and bring society closer to dealing with the tragedy of the violent deaths of thousands of people every year.