By Sasha Turner

Enslaved African Americans hoe and plow the earth and cut piles of sweet potatoes on a South Carolina plantation, circa 1862-3 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress).

On March 24, 2017 the United Nations commemorated its ten-year anniversary for the International Day of Remembrance honoring the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. This year, the theme chosen for the commemoration is “Remember Slavery: Recognizing the Legacy and Contributions of People of African Descent.” In the keynote address, delivered by Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture urgently called on us to be vigilant in recognizing the ways in which the legacy of slavery continues today. Cloaking the history of slavery in silence, Bunch argues, permits the violence of slavery to live on, dishonoring the struggles, losses, and strength experienced by our ancestors.

It is fitting that the UN-designated International Day of Remembrance falls on March 25, coinciding with Women’s History Month. Indeed, any attempt to remember the enslavement of African peoples is incomplete without considering women’s experiences in slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. In addition to dominating as field workers and sometimes outnumbering men on slaving ships departing the coasts of West and West Central Africa, enslaved women’s reproductive capacity shaped the economic parameters and racial logic of Black bondage. As one UN General Assembly member further cautioned, modern-day slavery, a multifaceted system that entraps over 40 million people, disproportionately affects women and children. Our attempts to address the legacies and new forms of slavery will therefore fall short if race is not considered in conversation with gender alongside significant variables like class and age. These must be understood as simultaneously operating and intersecting aspects of oppression and exploitation that are often invisible and structural.

Enslavement was not just about the exploitation of the labor of enslaved Africans. It was also about creating a unique set of power relations that protected, perpetuated, and strengthened the system of enslavement. The structures that propped up enslavement, though not immediately perceptible, had deadening consequences for enslaved people.

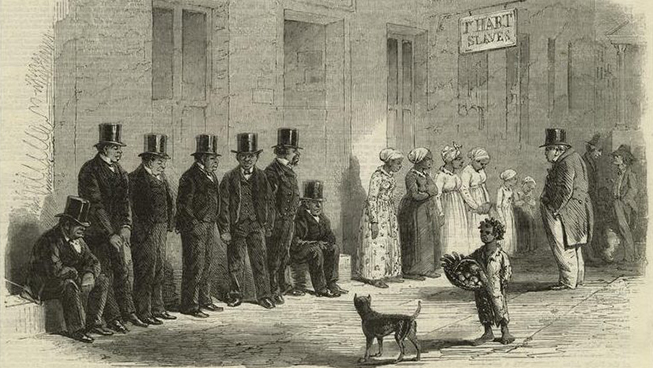

“Slaves For Sale, A Scene In New Orleans.” 1861. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The deep-seated impact that slavery had on enslaved populations is best captured in the concept of “social death,” popularized by sociologist Orlando Patterson and familiar to scholars but perhaps not as recognizable beyond the academy. Enslavement disrupted and severed social and familial ties. The annihilation of family bonds took place in the violent acquisition of Africans from the interior of West and West Central Africa, the physical and agonizing separation of captives from their life, family, and community, and the anguish of their Middle Passage journey to the Americas. African people became outsiders because they no longer belonged to or were a part of the social networks and communities of their African homeland. Although much scholarly work has shown the incredible ways in which captive Africans forged a deep sense of kinship with others, created close-knit communities, and fought to secure their familial ties, enslaved people’s existence was subjected to arbitrary change and profound loss. In this respect, this was a life of living death. At any given moment, familial and community bonds could be disrupted at masters’ behest.

The judiciary system that underlay American slavery also ensured that the racialized violence of social death was gendered. The gendering of social death took form in the legal code partus sequitur ventrem–offspring follows belly. Enacted in slave colonies across the Americas from Brazil, to Jamaica, and Virginia, this law bound enslaved women’s fertility to the reproduction of slavery. In places like the Virginia House of Burgesses, which enacted partus sequitur ventrem in 1662, lawmakers broke with the Roman origins of English Common Law, the legal foundation of the colonies. Roman Law required that children take their father’s status if the parents were free, but the mother’s status if the parents were slaves. Virginia’s 1662 law, like those of many other slave colonies, collapsed this distinction and determined all children’s status according to their mothers’ status.

Declaring that “all children born in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother,” this 1662 Virginia law alienated Black women’s fertility from the reproduction of kinship and family. Instead, it inextricably bound Black women’s reproduction to the perpetuation and the maintenance of slavery, as their offspring were assigned to be consumed by slavery’s political economy. The Black woman’s body was legally codified as the site where more slaves were produced. This law made slaves’ status inheritable through mothers and installed and institutionalized a racialized hierarchy.

Making slave status inheritable through mothers ensured that the relationship between masters and female slaves was not only one involving manual, productive labor in the tobacco, cane, cotton, and rice fields. Masters also bound the reproductive labor of enslaved women to their profits by claiming children born to enslaved mothers as their chattel property. Prior to Virginia’s 1662 statute, enslaved mothers made arrangements for the guardianship and residence of their free-born children. The law denied enslaved women rights of access to and ownership of their children who, after 1662, counted in slaveholding ledgers as property and future workers. Similar laws, like the siete partidas that governed Spanish territories, offer a clarifying clause on the property implications of partus sequitur ventrem. “Slaves are considered more as commercial items than people; hence property rights are acquired in the same way as they are with objects…thus he who is born of a slave mother is also a slave, even if his father is free…so the mother’s owner also owns her child, just as the sheep’s owner owns her lamb.” In places like North America that grew less reliant on the transatlantic trade in Africans before the start of the nineteenth century, the continued productivity and profitability of the American economy depended significantly on Black women bearing children into enslavement.

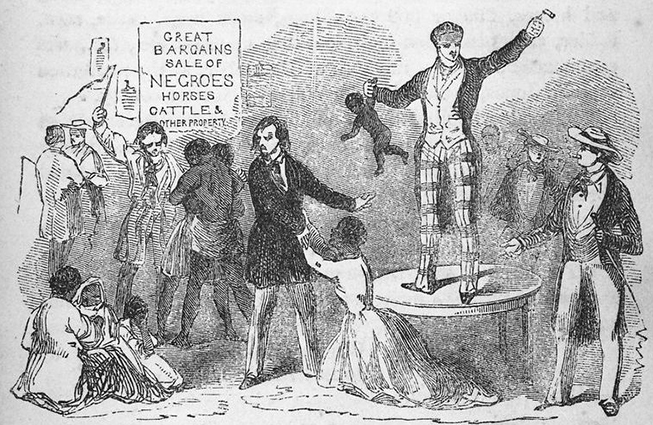

“Husbands, wives, and families sold indiscriminately to different purchasers, are violently separated; probably never to meet again.” 1853. New York Public Library.

An invisible but highly lethal violence was enacted on enslaved women in slave accounts that recorded only mothers’ names and disregarded fathers. Probate records stipulated that “the first Negroe child boy or girl that shall be borne out of the body of …will be given to….” and terms of sale contracts calculated value according to “the increase and offspring of ye said woman.” The violence of the law was also in the terror and dread mothers experienced, watching their bellies grow, fearing that their children might be “equally divided” among heirs and used to settle outstanding debts, mortgage transfers, and marriage settlements. There was a peculiar violence enacted in the sale and rental of enslaved women who “recently gave birth” and whose “abundant milk” created new opportunities for their owners to peddle them to renters or buyers. New mothers were not only denied the liberty to nurse their own babies but they were also prevented from expressing feelings of grief and mourning when it came to their children. In places like nineteenth-century Louisiana that did not replenish its population by birth, when enslaved infants died mothers barely had time to respond to their loss. Childless mothers were hurried to nurse the babies of their masters and mistresses to encourage their continued lactation and to prevent “milk spoilage.” These and other “unspeakable things unspoken,” to invoke Toni Morrison’s framing, was the gender and racial violence that conspired to drive enslaved women to take the lives of their own children. Even then, enslaved women were reminded that their Black bodies produced property, not people, as they were charged with the destruction of property rather than the murder of a human being.

Sanctioned to protect the commercial interests of the propertied white elite, partus sequitur ventrem was a law that hardwired the consumption and exploitation of Black bodies into America’s political and economic DNA. This legal sanctioning signaled a consistent thread that weaves the various iterations of Black and gendered unfreedom and exploitation since emancipation. To highlight the point Ava Duvernay’s film, 13th, makes, slavery might have been struck down by the pen, but it has morphed and lives on through the ages. It was reincarnated through the convict leasing system that exploited the labor of incarcerated people, most of whom, in southern states like Georgia, were predominantly African American and were imprisoned through Jim Crow’s fabrication of black criminality. It was reincarnated through the “war on drugs,” which fostered mass racialized incarceration through the unequal policing and sentencing of Black and white drug users. It lives today reincarnated through the “get tough” or “zero tolerance” policies on school offenses by rejecting juvenile delinquency (e.g. throwing food, cursing, truancy, etc.) as a social service measure and benevolent adolescence/developmental health intervention. It imposes criminal sanctions that funnel mostly Black children from schools to prisons in a system now known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

What has resulted through the legacy of Black slavery in America is a prison industrial complex. A system that yields profits according to the number of people incarcerated and uses the labor of incarcerated people in a variety of industries portends a new “social death” for Black families and communities.

To remember the legacy of slavery requires vigilance. But what is required to honor the struggles, losses, and strength experienced by our ancestors is not just a vigilance that attends to overt racism and prejudice in the here and now. Vigilance, in the words of Bunch, requires us to make the long history of the “unseen, visible.”