A Polisario Front official surveys the Moroccan Berm in the Western Sahara. John Bolton and a former German President have helped spur the first negotiations over the disputed desert territory in six years. Photograph by Nicolas Niarchos

By Nicolas Niarchos, The New Yorker —

For the past forty years, tens of thousands of Moroccan soldiers have manned a wall of sand that curls for one and a half thousand miles through the howling Sahara. The vast plain around it is empty and flat, interrupted only by occasional horseshoe dunes that traverse it. But the Berm, as the wall is known, is no natural phenomenon. It was built by the Kingdom of Morocco, in the nineteen-eighties, and it’s the longest defensive fortification in use today—and the second-longest ever, after China’s Great Wall. The crude barrier, surrounded by land mines, electric fences, and barbed wire, partitions a wind-blasted chunk of desert the size of Colorado known as the Western Sahara. Formerly a Spanish colony, the territory was annexed by its northern neighbor, Morocco, in 1975. An indigenous Sahrawi rebel group, called the Polisario Front, waged a guerrilla war for independence. In 1991, after sixteen years of conflict, the two sides agreed to a ceasefire. The wall keeping the foes apart stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the mountains of Morocco, roughly the distance from New York City to Dallas.

Late last year, I visited the Berm from the Polisario side, to the east, accompanying a handful of supporters of the group from around the world. Until we were about a hundred feet away, I didn’t sense that I was anywhere in particular in the expanse of the desert. My Polisario guide pointed out painted rocks indicating a minefield ahead. A few feet away, an unexploded mortar shell lay in the sand. We walked into a United Nations-controlled buffer zone and the Berm appeared in front of us, rising about six and a half feet behind a barbed-wire fence. I glanced left and right. The wall seemed to stretch endlessly, almost into the blue sky.

As we approached one of the tent-topped fortifications that dot the length of the Berm, a handful of Moroccan soldiers began to scurry around inside. “Will they shoot?” I asked one the Polisario guides. We could see the peaks of the soldier’s flat caps. “No, no,” he replied, laughing. He said that Sahrawis often demonstrate in front of the wall, demanding that Morocco leave the territory. “They’re used to this.” Two women began to shout abuse at the soldiers about Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. “Mohammed, you asshole,” they screamed. “The Sahara is not yours.”

Today, Morocco controls the western eighty per cent of the disputed territory, and the Polisario (which stands for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro) occupies the rest. The Polisario movement initially began as an armed rebellion against Spanish occupiers. Today, the Polisario calls Western Sahara “Africa’s Last Colony,” asserts that Morocco has replaced Spain as colonizer, and accuses the kingdom of exploiting the territory’s resources. Negotiations have repeatedly stalled, making Western Sahara the site of one of the world’s oldest frozen conflicts. The Polisario’s self-declared Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is recognized by the African Union and Algeria, which has given the group military support for decades and currently hosts more than a hundred and seventy thousand Sahrawi refugees in squalid camps.

Women at a traditional festival at the Boujdour camp near Tindouf, in southern Algeria. Sahrawis try to keep traditions alive in the camps. Photograph by Nicolas Niarchos

Morocco has poured money into its side of the Berm, expanding cities and developing tourism. But the Polisario accuses the kingdom of filling the territory it controls with secret police and soldiers, and of violently suppressing free speech and pro-independence protests. Videos abound online of police roughing up Sahrawi protesters. Omar Hilale, the Moroccan Ambassador to the U.N., denied the accusations of human-rights abuses in the territory and blamed incidents of violence on unlawful protests. “You want to protest, you have to register—everywhere, even here in the United States,” he told me. Hilale pointed the finger at Algeria, which he said had sent trained rabble-rousers into Western Sahara. Morocco’s largest foreign backer is France, the country’s former colonial overlord, and the French and Moroccan leadership retain strong political, economic, and personal ties. French companies frequently use Moroccan firms to invest in Africa, where they are often unpopular due to their colonial and postcolonial history. Many French politicians keep lavish holiday homes in Morocco.

On December 5th, for the first time in six years, negotiations were held in an effort to initiate a resolution to the conflict. To the surprise of longtime observers, the talks proceeded civilly and the parties agreed to meet again in several months. Officials present told me that President Trump’s new national-security adviser, John Bolton, played an important role in getting the groups to the table. “John Bolton and the enormous engagement the Americans are now putting in helped a lot,” a senior official close to the talks told me. Some diplomats involved in the negotiations call the changes “the Bolton effect.”

At an event in Washington in mid-December, where the Trump Administration’s new Africa strategy was unveiled, Bolton told me that he was eager to end the conflict. “You have to think of the people of the Western Sahara, think of the Sahrawis, many of whom are still in refugee camps near Tindouf, in the Sahara desert, and we need to allow these people and their children to get back and have normal lives,” he said.

Bolton knows the conflict well. He worked on the U.N. peacekeeping mandate for the region in 1991, and, starting in the late nineties, he was part of a U.N. negotiation team, led by James Baker III, the former Secretary of State, which came close to brokering an agreement to hold an independence referendum in the Western Sahara. (The Polisario agreed to the proposal, but Morocco did not.) The conflict, Baker told me in an interview in Houston, “has not been handled well, and that’s why it continues to persist.”

Since Bolton’s appointment, in March, there has been a flurry of activity regarding the Western Sahara conflict at the U.N. and in the State Department. “There are two Americans who really focus a lot on the Western Sahara: one’s Jim Baker, the other’s me,” Bolton told me. “I think there should be intense pressure on everybody involved to see if they can’t work it out.” This spring, at the insistence of the U.S. and to the chagrin of Moroccan and French diplomats, the U.N. peacekeeping mandate for the Western Sahara was extended by only six months rather than a year. (Bolton has long contended that the U.N. peacekeeping mission there has prolonged the conflict by detracting from efforts to resolve the underlying issues.) In October, the mandate was renewed for another six months. “After twenty-seven years, I don’t get impatient on a daily basis,” Bolton told me. “I just get impatient when I think about it.”

Bolton has repeatedly accused Morocco of engaging in delaying tactics to stymie negotiations. He wrote, in 2007, “Morocco is in possession of almost all of the Western Sahara, happy to keep it that way, and expecting that de facto control will morph into de jure control over time.”

Many Moroccan observers believe that Bolton is sympathetic to the Polisario. “John Bolton has distinguished himself by taking positions that are openly close to those of the separatists,” Tarik Qattab wrote in a story, this spring, for the Moroccan news outlet Le 360, which reflects the views of the government. Moroccan officials have also mounted a concerted effort to curry favor with Trump and Bolton. In May, Morocco cut off diplomatic relations with Iran, one of Trump’s most bitter enemies. Then, in September, the Moroccan foreign minister claimed in an interview with the conservative Web site Breitbart that the Polisario was being provided military training and weapons by Hezbollah, an Iranian proxy. (Morocco gave no proof of these claims, and analysts told me that such a connection was highly unlikely.)

Polisario officials, for their part, have welcomed the renewed U.S. engagement. Trump and other world leaders, they say, would create good will in the Arab world if they broker a peace settlement. European governments have also demonstrated interest in resolving the dispute; last year, Horst Köhler, a former German President, was appointed U.N. Special Envoy for the region. Köhler has long advocated solving internal problems in Africa in order to slow the flow of migrants northward. So far, he has been a forceful presence in the talks.

Initially, Morocco refused to meet with the Polisario, and the parties even fought over the shape of the bargaining table. But Köhler managed to hash out a format seen as a concession to all sides. Eventually, the participants—which included Morocco, Mauritania, Algeria, and the Polisario Front—met, in Geneva, on December 5th and 6th. Hilale, the Moroccan Ambassador to the U.N., was present. The talks, he told me, “took place in very respectful atmosphere and ambience.”

After the first day of the meeting, the delegates had a Swiss fondue dinner together. “The Europeans had to explain to the parties how that worked, and that worked to bring them together,” the official close to the talks told me, jokingly referring to the meal as “fondue diplomacy.” By the end, the Algerian foreign minister began to address the Moroccan foreign minister by his first name. However, when the Polisario suggested confidence-building measures, such as removing the mines along the Berm and releasing political prisoners, during the formal talks, they were rebuffed.

By the afternoon of the 6th, a communiqué was agreed upon that called for more talks in the coming months. “From our discussions, it is clear to me that nobody wins from maintaining the status quo,” Köhler said. The Polisario praised the renewed U.S. involvement in the talks and called for “a process of self-determination in Western Sahara.” But the Moroccan foreign minister rejected the idea of a plebiscite. “Self-determination, in Morocco’s view, is done by negotiation,” he said. “A referendum is not on the agenda.” A week later, at the event in Washington, Bolton appeared to back a referendum. “You know, being an American, I favor voting,” he said. “All we want to do is hold a referendum for seventy thousand voters. It’s twenty-seven years later—the status of the territory is still unresolved.”

Until now, the United States has largely backed Morocco in the conflict. During the Cold War, the Polisario was seen as pro-Soviet and received support from Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya, as well as Algeria and Cuba. The U.S., under both Republican and Democratic Administrations, sold hundreds of millions of dollars of weapons to the Moroccan armed forces. Baker remembers the conflict being portrayed in stark Cold War terms when he visited Morocco. “When I was Treasury Secretary, the Moroccans came to us and they wanted help in their war against Polisario,” Baker told me. “I gave them overhead intelligence.” The intelligence, and direct U.S. military support, were instrumental to the Moroccans as they built the Berm.

After the 9/11 attacks, the Moroccans tried to once again portray the Polisario as the enemy, arguing that an independent Western Sahara would become a haven for terrorists. Baker, in his capacity as the U.N. envoy, put forward two plans for the region. The first offered the Moroccans control over the Western Sahara but allowed the Sahrawis autonomy. The Polisario rejected the proposal, and it was never presented formally to the U.N. Security Council. Baker’s second plan called for an independence referendum by Sahrawis and Moroccans living in the territory after a period of autonomy under a Sahrawi government. In 2003, Baker’s second proposal was unanimously endorsed by the Security Council, but the Moroccans worried that they might lose the referendum. King Mohammed wrote to George W. Bush to scupper Baker’s plan, raising the threat of the “redeployment of terrorist groups in the region.” Elliott Abrams, then a key adviser to the National Security Council, argued that the Polisario was no friend to the United States. “I didn’t see any reason to think that it would turn into a democracy, or that it would be pro-Western,” Abrams told me, in an interview. Baker’s proposals were abandoned.

Today, the territory is caught in diplomatic limbo: the Polisario insists on a referendum, and Morocco insists that the region should be given a more limited autonomy, under the kingdom’s sovereignty. (Bolton has dismissed Morocco’s proposal in the past.) Baker told me he was still perturbed by the breakdown in negotiations. “I came up with a pretty damn good plan, I thought,” he said. The problem, he said, was that the international community and the U.N. Security Council didn’t support him. “You know, the U.N. can only be as effective as its member states,” he said. “The member states don’t want to solve this. They’re not willing to use political chips to solve it, so it ain’t going to get solved.”

The best-known among the Sahrawi protestors demonstrating against Moroccan rule in the Western Sahara is Aminatou Haidar, a slight, birdlike woman in her early fifties. She was nominated for the 2008 Nobel Peace Prize and has been called the “Sahrawi Gandhi.” A practitioner of nonviolent resistance, Haidar has been beaten, tortured, imprisoned, detained, and interrogated by the Moroccan security services for her protests against the kingdom’s rule in the Western Sahara. In 2009, after travelling abroad, she was barred from returning to the territory, and she went on a hunger strike that left her bones brittle and the vertebrae in her back warped.

I met Haidar last year, in the Canary Islands, in the lobby of a nondescript hotel. She wore a yellow-and-gray mulafa, a traditional veil worn in Northwest Africa, which drew the occasional glance from European holidaymakers walking nearby. She squinted at me through thick-framed glasses. Her eyesight was damaged, she said, when guards blindfolded her for long periods in a Moroccan jail. “I’ve lived the suffering in my own flesh,” she told me. On the day I met her, Sahrawi demonstrators in Laayoune, the capital of Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, had been attacked by the police. “During the last six months, we have registered, I think, eighty-six demonstrations that were stopped or repressed,” she said.

In 1987, when she was twenty, Haidar organized a demonstration in advance of an official U.N. visit to the Western Sahara. Moroccan police came to her house the night before the U.N. team arrived. “I was arrested. They put me in a car, and they started to quickly drive around the street,” she said. The car circled the streets of Laayoune in order to give the impression that they had travelled farther than they actually had. She was worried that she had been taken to a secret jail inside Morocco, as some of her relatives had been, and that she would never return. In fact, she had been taken to a police barracks near her home.

For the next four years, she was imprisoned in various jails, and her family was not told of her whereabouts. For the first year, she lived in solitary confinement. “I contracted rheumatism, because I was thrown into a corridor where it was really cold. And in the summer it was boiling,” she told me. In the second year, Haidar was placed in a cell with other detainees. She said that some of her fellow-prisoners told her that they were bitten by dogs set on them by policemen.

Haidar was released in 1991, as the Moroccans and the Polisario signed a ceasefire. The two parties agreed that the U.N. would broker a vote on national self-determination. Disagreements over who would be allowed to vote delayed the referendum, which has still not taken place. Moroccan officials barred journalists and human-rights organizations from entering the territory and investigating police abuse. “We were totally isolated from the outside world,” Haidar said. Moroccan officials confiscated her passport in 1987 and declined to issue her a new one for nearly two decades.

Last year, I tried to visit Laayoune and make sense of two contradictory narratives that have emerged from Western Sahara. Haider and other independence supporters have told horror stories, yet tourists post enthusiastic reviews of the area’s resorts and beaches. I asked my brother, who is a photographer, to join me. Before leaving, I contacted local supporters of independence, including Haidar, and set up interviews with them in the city.

After we landed in Laayoune, a swarm of policemen wearing hats with red bands walked across the tarmac toward our plane. As the other passengers on our flight began to file off, my brother and I were told to stay seated. The authorities knew of our arrival, either through the use of informants, or by intercepting my communications with independence supporters. A policeman in civilian clothes came onto the plane and took our passports. When I tried to stand, I was ordered to sit down.

Plainclothes policemen came onto the plane and began filming us and yelling; about ten minutes later, a Moroccan official in a grimy blue robe who spoke no English arrived. A stewardess who spoke French was too terrified to say anything, so a gate agent who spoke a smattering of English was ordered to translate. For about half an hour, the official shouted at us, reminding us of Morocco’s support for the post-revolutionary United States. Then he announced that we were being deported. A short time later, the plane we were sitting on filled with passengers and took off for Las Palmas, the largest city in the Canary Islands.

The following morning, I found an article on a Moroccan news site reporting our deportation, along with the false claim that we had planned to stage a sit-in. The story stated that “deporting the two Americans forced the organizers to cancel the sit-in.” Independence supporters in Laayoune told me that a protest was, in fact, held after word spread of our deportation. A video was posted on YouTube in which a protester said that seventy policeman had attacked marchers. “Despite the suffocating siege, we went out to scream loudly before the invaders,” he said. “They beat me harshly. . . . It still hurts.”

It is impossible to know how many Sahrawis support Moroccan rule. In the portion of Western Sahara under Moroccan control, residents pay no taxes and receive generous unemployment benefits. But Moroccan officials operate a vast patronage system and corruption is endemic. Hundreds of thousands of Moroccans have migrated south and, in some cases, have been awarded key political and business positions. Hilale, the Moroccan Ambassador to the U.N., told me that many Sahrawis have embraced Moroccan rule. “They are ambassadors, they are businessmen, they are professors, they are everywhere,” he said.

The royal family has used the dispute to solidify popular support since the nineteen-seventies, when elements in the armed forces tried to wrest power from the monarchy. Moroccan officials argue that Sahrawi nationality has been effectively invented by the Polisario, and that the Western Sahara belonged to Morocco before Spain invaded, in the nineteenth century. Polisario supporters contend that Sahrawi society and culture emerged independently, during the centuries they spent as nomadic pastoralists. Histories of the Western Sahara suggest that Morocco’s rulers had little control over the territory; in 1767, one Moroccan sultan wrote to the King of Spain that the tribesman were “greatly separated from my dominions and I do not have power over them.” Today, King Mohammed dismisses the independence movement as “tribal fanaticism.”

The dispute is costly for the kingdom. Fouad Abdelmoumni, a Moroccan economist with Transparency International, said that, since 1975, the kingdom has spent some eight hundred and sixty-two billion dollars on, among other things, military deployments, infrastructure, and unemployment benefits in the territory. King Mohammed VI has said that, for every dirham of profit that Morocco makes in the Western Sahara, it spends seven.

However, control of the Western Sahara is so deeply embedded in Morocco’s national identity that any government that allowed it to slip from Rabat’s control would likely be toppled. A former journalist from Morocco told me that the local media is banned from describing the situation as an “occupation.” He said that, in the eyes of the kingdom, “either you’re a separatist, or you recognize what is officially believed as the truth, which is that it’s an integral part of the national territory. Once you have claimed for years and decades that this is a sacred cause,” he said, “there is no arguing about it and no conversation.”

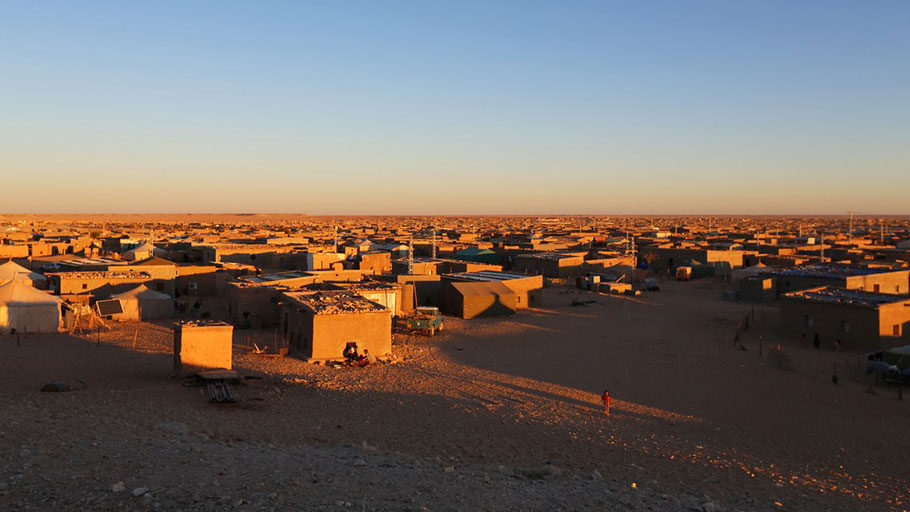

Last year, I flew to Tindouf, a remote desert town in southern Algeria that is ringed by five Sahrawi refugee camps. The plane carried an incongruous mix of grim-faced Sahrawis and boisterous Spanish aid workers. (Spain has hundreds of humanitarian organizations that send volunteers and donations to the camps, and place Sahrawi children in Spanish homes during the hot summer months.) At the airport, a Polisario representative handed me a landing card, in Arabic, Spanish, and English, welcoming me to the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. A battered car took me to the Smara camp, the largest of the five, with some fifty thousand residents. I climbed a small hill and saw houses and tents stretching all the way to the horizon. The U.N. recently estimated that more than a hundred and seventy thousand people live in the camps around Tindouf.

For a quarter century, Sahrawi refugees have lived lives of suspended animation. Each camp is named after a city in the Moroccan-occupied part of Western Sahara. Conversations center on independence and the indecision surrounding the referendum. The future is more of a focus than is the present. As Albeitoun Mohamed Abt Mohamed Hnini, a local administrator in her early sixties, put it, “Through all these difficulties, there was the conviction that we weren’t here for bread, we weren’t here for money, but that we wanted to create an alternative community to fight for our freedom.”

The Smara camp in Tindouf, the largest of the Sahrawi camps. The U.N. estimates that some fifty thousand refugees live there. Photograph by Nicolas Niarchos

Schools operate and dispensaries provide food and medicine. A legal code is in force, and courts try cases. Over the decades, economic conditions in the camps have improved. In the nineteen-seventies, residents lived in communitarian hardship. These days, there is quasi-capitalism, with markets and a small amount of commerce. Some residents cite the improvement in living standards as a sign of the inexorable utopia Western Sahara would become after independence. They told me that the territory would become wealthy from its abundant phosphate reserves and fish stocks. Sometimes the optimism felt overblown: some residents predicted that Western Sahara would be the next Kuwait, yet the disputed territory has no proven oil reserves or natural resources beyond phosphate and fish.

Moroccan officials argue that the Polisario tightly controls the camps and forces residents to support its call for independence. Robert Holley, a retired State Department official who later worked as a registered foreign agent for the Moroccan government, describes the camps as “gulags.” He told me that foreigners were shown a Potemkin village when they visited. But, during my two weeks in Polisario-controlled camps and territory, I was able to roam without a minder. (My only limitation was a nightly curfew, which was imposed after jihadists from northern Mali kidnapped three European aid workers from the camps, in 2011.)

The Polisario Front has worked to abolish class, gender, and racial differences in Sahrawi culture, but vestiges of each remain. Hnini, the administrator, told me that women in the Sahrawi refugee camps enjoy a level of empowerment unusual in the wider Arab world: women can receive guests alone at home, divorce, and travel to Mecca without a male guardian. The Polisario has also banned slavery, which was practiced for decades by the Sahrawis of the Western Sahara, who were once known as the most ruthless slavers in the region. An anti-slavery organizer in neighboring Mauritania told me that he thought war and hardship had transformed Sahrawi society and that racism is now rare. “This may have been the only good thing that came from this war,” he said.

During one of my nights in the camps, I stayed with Takween Mohamed, an English teacher with two young children. Her husband was more than a thousand miles away, serving in the Polisario’s armed forces. In the evenings, we watched Algerian television in a small room with a corrugated iron roof and a single, low-energy bulb hanging from the cobwebbed ceiling. The only source of heat was a tiny charcoal stove used to boil tea. Mohamed and her children wrapped themselves in blankets as the cold night air seeped through cracks in the door. As we stared at the screen, she offered me a dish of peanuts and some high-energy biscuits provided by the World Food Programme.

Algerian television was remarkably boring. News bulletins recounted the opening of a new cement plant. Commercials were the real fun for Mohamed and her four-year-old son, who had memorized some of the jingles and would dance and sing along to each one. Mohamed’s favorite was an ad for the “Gazelle d’Or,” a resort. The camera swept across the sparkling complex, showing sunsets and palms, fluffy beds, and a swimming pool next to a clean, modern hotel with a domed roof. “That is the most beautiful place,” she told me.

On a Monday in mid-December, as I was making the final preparations for this story, Hilale, the Moroccan Ambassador to the U.N., invited me to his residence for lunch. The next day, I was ushered into a limestone town house on the Upper East Side of Manhattan by a butler in a tuxedo, who took me to a lushly decorated sitting room where he offered me a selection of juices. After my experience on the plane in Laayoune, I wasn’t sure what to expect, but, when Hilale arrived, with a short mustache and wearing a brown jacket, he was charming. He told me that he had studied at university with the founder of the Polisario Front, El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed, whom he remembered as a “good student” who “claimed that the Sahara was Moroccan” during the Spanish colonial period.

Over a lunch of chicken tagine and couscous, Hilale told me that the Western Sahara conflict was a “residue of the Cold War.” I asked him why I had been expelled from Laayoune, and he said that I didn’t have the correct permissions. He told me that Moroccan rule has brought prosperity to the former Spanish backwater. “Roads, airports, hospitals are under way,” he said.

When I asked about Bolton, and the increased engagement with the issue from the U.S. in the past couple of months, he pointed to the closeness of the ties between the Moroccan government and Washington. He shrugged off the shortening of the U.N. peacekeeping mandate to six months, a process spurred by Bolton. “For us we work with it, if they want six months, O.K. They want one year, it’s O.K. for Morocco,” he told me. “Our bilateral relationships are so strong that they will never be jeopardized by any person.”

But Hilale drew a firm line at questioning Moroccan sovereignty, and insisted that there is “no way to organize a referendum—referendum is dead.” As is Moroccan policy, Hilale framed the debate as one between Morocco and Algeria, rather than between Morocco and the Sahrawis. “For Moroccans, Sahara is a national cause,” he told me. “For Algeria, Sahara is just an agenda.” I asked him what he thought Algeria wanted from the continued impasse over territory. “We are asking them, ‘Come around the table and tell us what you want,’ ” he said. “But, for the time being, we are still waiting.”

In an interview in the camps, Brahim Ghali, the Polisario’s current leader, assured me that the movement’s dream of an independent Western Sahara remains viable. Ghali has been involved in the movement since it fought the Spanish, in the nineteen-seventies, and was appointed its leader in 2016. Clipped and military in his bearing, he wore a gray, crescent-shaped mustache and a military jacket with a blue button-down shirt beneath it. He insisted that the Polisario was ready to “coexist” with Morocco as an independent state and blamed the international community, which he said “takes our suffering very lightly,” for the decades-old impasse.

Since the early two-thousands, some dissidents have questioned the Polisario’s insistence on reaching a negotiated settlement and have called for refugees to once again take up arms against Morocco. Many of the young people whom I spoke to echoed this sentiment. “We are convinced war is the only way forward,” Mohamed Salem Qatri Nazem, a twenty-six-year-old trucker, told me. “We have lived through forty-four years of resistance.”

Anna Theofilopoulou, a former U.N. official and expert on the conflict, told me that Ghali and his generation face a leadership challenge. “The Polisario old guard, who, with all their faults, have managed to keep the more radical elements in check, are slowly dying,” she said. “Even now, Polisario is being challenged by the younger generation for going along with the U.N. process that is not likely to bring them any closer to what they had achieved with Baker.”

Ghali told me that the situation spoke to the failures of the U.N.-backed peace talks. “In 1991, we put all our trust and confidence in the international community,” he said, referring to the ceasefire. Since then, three generations of people have lived in the camps, and the young are fed up. “Our task is not easy, to keep those young people calm, to keep them patient, and we are aware that their patience is wearing out.”

Since 2011, as states such as Libya and Mali became destabilized, drug trafficking and fundamentalism have spread to much of the greater Sahara. The Polisario has been effective in limiting Islamist preaching in the camps, but small numbers of young people have been radicalized, illustrating the dangers of waiting too long to resolve the conflict. A year after the three aid workers were kidnapped from the camps, roughly twenty-five young Sahrawis travelled to Mali to fight alongside Islamists there. One of the most prominent jihadists in the Sahara today is Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, an ethnic Sahrawi who was born in Laayoune and, as a young man, protested against Moroccan rule. Al-Sahrawi has now reportedly allied himself with isis and was part of a group responsible for killing four American soldiers in Niger, last October. “Somewhere along the line, he stopped believing in political struggle and moved into jihadism,” Hannah Rae Armstrong, a specialist for the Sahel region with the International Crisis Group, told me. “The inability to find a political solution to this issue is forcing the younger generation to look for alternatives.”

Near the end of my trip, I took a seven-hour drive across the desert and visited the strip of Western Sahara controlled by the Polisario. We stopped near the tiny settlement of Bir Lehlou, in what the movement calls the “liberated zone,” at a camp that served as a base for de-mining operations. The camp was run under the auspices of Norwegian People’s Aid, a humanitarian N.G.O. Many of the Sahrawi de-miners I met there told me that, referendum or no referendum, war or no war, they would build a state on their own, even without international approval. Moroccan officials have argued that doing so is a violation of the 1991 ceasefire agreement, but their protests seem to have merely emboldened the young Sahrawis I met.

One of the de-mining crews I met was called Team Bravo. The half-dozen young women and men on the team told me that a first step toward creating a state is clearing the territory that the Polisario controls of land mines and unexploded ordnance. There are around nine million such explosives in the Western Sahara, making it one of the most heavily mined places in the world. Sometimes children pick up the bombs, members of the crew told me, thinking they are toys. They said that de-mining would allow people to live and herd camels in the area again.

Elwali al-Abeidi, the leader of a de-mining crew, at the contaminated site of Lah’waj Telli, in Western Sahara .Photograph by Nicolas Niarchos

I watched the team creep across the vast desert plain, fifty centimetres at a time, scanning for mines in a bitter winter wind. They wrapped their heads and faces in cloth to protect their skin from the dust; large dark glasses screened their eyes from the glaring sun; blue anti-explosive vests hung to their thighs. The blood type of each person was written on the front of his or her vest. Since the effort began, in 2016, the teams have cleared more than five hundred square miles of explosives.

Elwali al-Abeidi, the team leader, showed me one of the explosives that his team had discovered, a silver cylinder the size of a tennis ball, ringed by stones that had been spray-painted red. Abeidi, a twenty-eight-year-old with a thin face and a scrawny beard, explained that it was a cluster bomblet that had likely been dropped by the Moroccan Air Force more than thirty years ago. He told me that the team would destroy it in a few days. It was probably American-made. I asked Abeidi how he felt clearing the explosives, considering that some people believe the war should start again. He grinned and said that he, too, believed that the Sahrawis should resume hostilities with the Moroccans. And, I asked, what about the ordnance that would be dropped in a renewed conflict? He looked at me for a moment and replied, “We’ll just clear it again.”