Not terribly long ago in a country that many people misremember, if they knew it at all, a black person was killed in public every four days for often the most mundane of infractions, or rather accusation of infractions – for taking a hog, making boastful remarks, for stealing 75 cents. For the most banal of missteps, the penalty could be an hours-long spectacle of torture and lynching. No trial, no jury, no judge, no appeal. Now, well into a new century, as a family in Ferguson, Missouri, buries yet another American teenager killed at the hands of authorities, the rate of police killings of black Americans is nearly the same as the rate of lynchings in the early decades of the 20th century.

About twice a week, or every three or four days, an African American has been killed by a white police officer in the seven years ending in 2012, according to studies of the latest data compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. That number is incomplete and likely an undercount, as only a fraction of local police jurisdictions even report such deaths – and those reported are the ones deemed somehow “justifiable”. That means that despite the attention given the deaths of teenagers Trayvon Martin (killed by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman) and Jordan Davis (killed by a white man for playing his music too loud), their cases would not have been included in that already grim statistic – not only because they were not killed by police but because the state of Florida, for example, is not included in the limited data compiled by the FBI.

Even though white Americans outnumber black Americans fivefold, black people are three times more likely than white people to be killed when they encounter the police in the US, and black teenagers are far likelier to be killed by police than white teenagers.

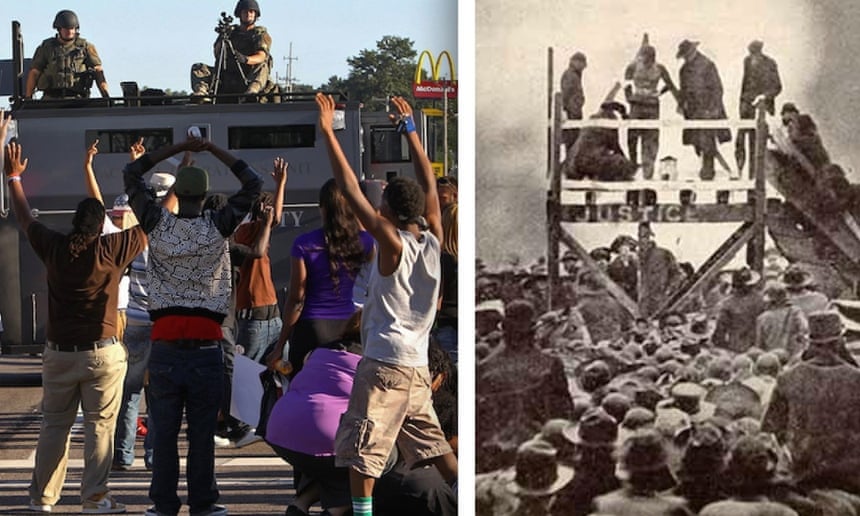

The haunting symmetry of a death every three or four days links us to an uglier time that many would prefer not to think about, but which reminds us that the devaluation of black life in America is as old as the nation itself and has yet to be confronted. Beyond the numbers, it is the banality of injustice, the now predictable playing out of 21st Century convention – the swift killing, the shaming of the victim rather than inquiry into the shooter, the kitchen-table protest signs, twitter handles and spontaneous symbols of grievance, whether hoodies or Skittles or hands in the air, the spectacle of death by skin color. All of it connects the numbing evil of a public hanging in 1918 to the numbing evil of a sidewalk killing uploaded on YouTube in the summer of 2014.

Lynchings were, of course, distinct from today’s police killings. They were ritualistic displays of public violence before sometimes thousands of people, including children. They were intended to reinforce the arbitrary rules of a race-based caste system, primarily in the American south. One white father in Texas took his toddler to a lynching in Waco in 1916 for that express purpose. He propped the boy up on his shoulders as 18-year-old Jesse Washington was burned alive. “My son can’t learn too young,” the man said.

But there are parallels between the violence of the past and what happens today. Images and stereotypes built into American culture have fed prevailing assumptions of black inferiority and wantonness since before the time of Jim Crow. Many of those stereotypes persist to this day and have mutated with the times. Last century’s beast and savage have become this century’s gangbanger and thug, embedding a pre-written script for subconscious bias that primes many to accept what they were programmed to believe about black Americans, whether they are aware of it or not.

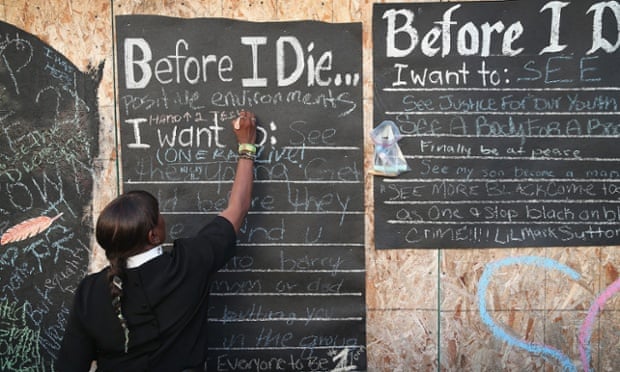

It is the ordinariness of the supposed infractions and the very human nature of the behavior of some of the victims that may be most heart-wrenching about both lynchings of the past and the public killings of today. In both cases, it has never taken very much for an African-American to lose one’s life, whether taking a hog during the time of formal Jim Crow or jaywalking three Saturdays ago in Ferguson. Or, in a stunning case in Brooklyn, New York, 19-year-old Timothy Stansbury Jr., unarmed and with no criminal record, was killed in 2004 as he walked up a stairwell. The officer who shot him said that he had been startled. A grand jury refused to indict.

It is the ordinariness of the supposed infractions and the very human nature of the behavior of some of the victims that may be most heart-wrenching about both lynchings of the past and the public killings of today. In both cases, it has never taken very much for an African-American to lose one’s life, whether taking a hog during the time of formal Jim Crow or jaywalking three Saturdays ago in Ferguson. Or, in a stunning case in Brooklyn, New York, 19-year-old Timothy Stansbury Jr., unarmed and with no criminal record, was killed in 2004 as he walked up a stairwell. The officer who shot him said that he had been startled. A grand jury refused to indict.

There has long been a readiness to see ordinary human behavior as criminal when that human is black, to see the death penalty as justified even for common missteps by black people. There seems to come a thirst for more incriminating evidence about the victim – a trace of marijuana in the blood, say, or a grainy selfie on Instagram with pants sagging low – a search for justification that the victims brought the trouble on themselves.

The demeaning objectification of the victim that was evident historically also persists to current times. During formal Jim Crow, the lynched body was sometimes left hanging for days or weeks as a lesson to people not to step outside the caste into which they had been born. In a similar way, Michael Brown’s body was left in the street in Ferguson for four hours in the August sun after he had been killed.

During formal Jim Crow, lynchers killed with impunity. Rarely was there so much as an inquiry. Sheriffs were often actively involved, in attendance or chose not to intercede. In many cases of police brutality today, the officers may be suspended with or without pay (if at all), reassigned to a desk job or may be returned to the streets.

Lynchings were spectacles with hundreds if not thousands of witnesses and were often photographed extensively. Now, much of the recent police violence has been recorded as well. The chokehold killing of Eric Garner on Staten Island, New York, the beating of great-grandmother Marlene Pinnock on a Los Angeles freeway and the gut-wrenching case of 17-year-old Victor Steen, tasered while riding his bicycle and then run over by the police officer in Pensacola, Florida, were all caught on videotape and have reached hundreds of thousands of watchers on YouTube – a form of public witness to brutality beyond anything possible in the age of lynching.

During the era of formal Jim Crow, white Americans were as safely disconnected from the lived experiences of black Americans as polls show that many are today. A Pew study last week found that 80% of black Americans polled, preoccupied by the killing of Brown at the hands of Officer Darren Wilson and its aftermath, felt that the case raised important issues about race. Only 37% of white respondents felt that way, due in part to de factosegregation and a majority status that does not require engagement with those outside their own group.

That racial isolation, combined with the negative messages embedded in American culture, create a lack in empathy that allows otherwise well-meaning people to turn away from the plight of fellow citizens. This implicit anti-black bias, present in varying degrees across races, extends to every sphere in American life, from harsher sentencing for black people in the criminal justice system to the likelihood that young men of color with clean records are less likely to be hired for jobs than white applicants with a criminal record.

Subconscious bias affects one’s actions before a person is aware of it and goes so deep that a study at the University of Milano-Bicocca found that when people are exposed to images of a needle piercing someone’s skin they experience a more dramatic, measurable, physiological response when white skin is inflicted with pain than when black skin is. Thus the brutality continues in part because the majority of American may literally be unable to feel the pain of their fellow Americans.