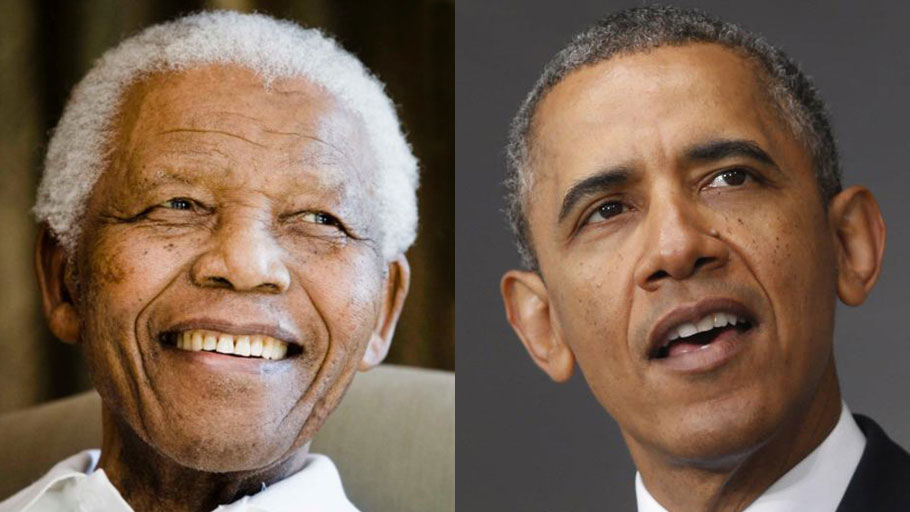

Image: Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama

When Barack Obama delivers the 16th Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture in Johannesburg on Tuesday, to mark this week’s centennial of the late anti-apartheid champion Nelson Mandela’s birth, the moment will be a deeply personal one for the former president.

His speechwriter Ben Rhodes has said that Obama considers it to be the most important speech since leaving office, and Obama has written that his political awakening began with a speech against apartheid, South Africa’s official government policy of racial segregation: Addressing students briefly at an anti-apartheid rally on the campus of Occidental College in Los Angeles in 1981 was “the first thing I ever did that involved an issue or a policy or politics,” he said when the former South African President died on Dec. 5, 2013.

But the speech will also have implications that stretch far beyond the personal. After all, the histories of the fights for racial justice in the United States and in South Africa have been closely intertwined for more than a century.

Here’s a look at the evolution of the overlap between the anti-apartheid movement and the U.S. civil rights movement, and what to know about the context that surrounds Obama’s historic speech.

American Inspirations and Early Cultural Exchange

The histories of both South Africa and the United States are deeply connected to stories of one race trying to dominate another. In the former, a minority of white colonial rulers exerted control over the black population in the region into the 20th century, with the apartheid regime persisting after independence; in the latter, slavery was followed by the passage of state and local “Jim Crow” laws that enforced racial segregation in many places.

So it’s no surprise that comparisons and exchanges between the two cultures are long-established.

Beginning around the turn of the 20th century, African-American missionaries and entertainers visited South Africa and black South Africans began to enroll at U.S. universities, both historically black colleges and universities as well as predominantly white schools. For instance, John Dube, who would become the first president of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1912, studied at Oberlin College in Ohio. He also wrote newspaper articles that kept black South Africans informed about what was happening with African Americans; black American publications such as the NAACP’s Crisis and Marcus Garvey’s The Negro World were available at libraries, and African-American sailors who docked at ports like Cape Town brought pop cultural influences with them. South Africans came to idolize African Americans actors and boxers like Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. (Mandela did too, as an amateur boxer himself.)

That exchange continued for decades, and cultural and political interchange often overlapped; for example, the famous South African singer Miriam Makeba married Stokely Carmichael, founder of the Black Panther movement, and Langston Hughes introduced many Americans to the facts of apartheid by publishing the work of black South Africans who couldn’t get published at home.

As black citizens of both nations struggled with discriminatory systems, progressive ideas spread between the two countries, even if the political activists who conceived them could not always be there to share them in person. In the 1920s, the South African government started becoming increasingly cautious about allowing African Americans into the country, launching a crackdown that would last until the end of apartheid in the early 1990s. The University of Fort Hare was established in 1916 to educate black South Africans so that they wouldn’t go to America to be educated, censors banned albums by Makeba and Harry Belafonte, and when Martin Luther King Jr. was invited to speak in South Africa by student groups in 1966 the government denied him a visa.

“The exchange that started in the 1890s made them [the South African government] nervous,” says historian Robert Trent Vinson, author of TheAmericans Are Coming!: Dreams of African American Liberation in Segregationist South Africa. “When blacks did come to South Africa, they were missionaries, apolitical blacks, or entertainment or sports figures there for a special reason [who] were closely followed by police.”

Some African-American civil rights leaders, like Malcolm X, made a point of traveling elsewhere in Africa and avoiding South Africa. Still, during this period leading into the 1960s, even though much work remained to be done in the United States, many South African activists found inspiration in what their counterparts in the U.S. were accomplishing.

“Black South Africans who couldn’t go to America idealized the African American position on some level, and saw them as racial role models who came out of hundreds of years of slavery and created some type of advancement for themselves — [whether] as sports heroes or writers — despite Jim Crow,” says Vinson. “Black South Africans were a generation behind in creating their own institutions.”

Nelson Mandela, Robert F. Kennedy and Civil Rights

In the 1960s, however, as the modern U.S. civil rights era reached its most famous moments, the dynamic between the two nations shifted.

A turning point came with the Sharpeville Massacre, when South African police on March 21, 1960, killed 69 black protesters in the town 40 miles south of Johannesburg. Shortly after, the government banned the ANC, which Mandela had joined in 1944. Among many in South Africa, there was a general sense that a new strategy was in order, moving away from the American model of nonviolence associated with the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. (Interestingly, both King and Mandela were inspired by the thinking of Gandhi, whose own time in South Africa helped shape his thinking on nonviolence.)

“In that context, the ANC leadership, including Mandela, took a very difficult decision to say, ‘We tried nonviolent protests every which way for last 50 years and have gotten nowhere. In fact things have gotten worse. We have to go underground. Either we submit or try to fight back,’” says Vinson. Later actions that made headlines included the car bomb that killed 19 outside of the headquarters of the country’s Air Force in Pretoria in 1983 and the explosion at a bar in Durban that left three dead and more than 60 wounded in 1986. (The ANC later apologized for the deaths of civilians in these cases, which it said was the result of “insufficient training.”) But as early as 1964, Mandela delivered his ‘I am prepared to die‘ speech, which resonated even with King, who wrote shortly after that he realized nonviolent resistance of the sort practiced in the United States was not really possible in South Africa. King had also warned shortly after the massacre that the incident “should also serve as a warning signal to the United States.”

Even as their tactics sometimes diverged, American civil rights activists continued to link their struggle to the struggle of black South Africans, to show that what was going on in the American South was just one of many black struggles for equality around the world.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) declared its ties to “the African struggle” during its founding conference in 1960, a nod to the continent-wide decolonization movement, and in 1964, for example, it sponsored a protest at the South African Consulate to the United Nations in solidarity with Nelson Mandela and other ANC members who were trial for acts of sabotage designed to bring down the apartheid regime. Martin Luther King corresponded with the first black African Nobel Peace Prize recipient Albert Lutuli, who won the award in 1960, and called him one of “the dedicated pilots of our struggle who have sat at the controls as the freedom movement soared into orbit.”

The ties between the two movements were further cemented in 1966. And at a time when many political black activists could not enter the country freely, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who had become a white ally of the U.S. civil rights movement, delivered his famous so-called ‘Ripples of Hope’ speech to white students at the University of Cape Town on June 6, 1966. “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope,” he said, “and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

And more militant American civil rights tactics were also influential in South Africa. Anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko “developed the black consciousness movement directly out of Black Power,” says Peniel Joseph, Founding Director Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin. Experts say the movement played a role in fostering a climate of discussion that empowered the students who protested mandatory classes in Afrikaans, the language of their colonial oppressors, in what’s now remembered as the Soweto Uprisings of 1976. What started as a peaceful protest ended with hundreds dead nationwide, and photography of the violence mobilized the international opposition to the regime.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement and Progress Made

Among white Americans, awareness of the inequality of apartheid regime in South Africa increased in the ’70s and ’80s, as President Ronald Reagan faced increasing pressure to impose economic sanctions on South Africa.

“By the 1970s, most of Africa is independent except South Africa, so South Africa looks strange. [People were thinking], didn’t we get rid of colonialism?” Vinson says.

Black activists urged Americans to boycott U.S. companies that did business in South Africa. Young African Americans were especially galvanized by the death of Biko, who died in a Pretoria jail cell after an assault by a white policeman. When Jesse Jackson ran for President in 1984 and 1988, he promised that as president he would restrict U.S. investments in South Africa and increase foreign aid to African countries. Awareness increased even more during the demonstrations that started outside the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C. on Nov. 1984, that, a year later, had lead to nearly 3,000 largely symbolic arrests, including 23 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, in what TIME called “one of the longest continuing demonstrations in U.S. History.” Protesters were joined by MLK’s widow Coretta Scott King, Arthur Ashe and Harry Belafonte, and even the children of Robert F. Kennedy, Rory and Douglas. Rosa Parks demonstrated outside the Embassy almost exactly 30 years after she became famous for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus.

“For black Americans, a response to South Africa is a response to them,” leading anti-apartheid activists Randall Robinson told TIME in 1985. “This is a test of our own democracy.”

The work began to pay off in October 1986, when Congress passed economic sanctions on South Africa. By the end of June 1987, more than 100 U.S. companies had left the country in the prior two and a half years, TIME reported. The dismantling of the apartheid regime would officially get under way in the early 1990s, when Mandela was released from jail and South African President F.W. de Klerk legalized political parties such as the ANC as long as they renounced violence as a tactic.

The regime officially ended with South Africa electing Mandela President in 1994. His election, to some African Americans in the U.S., represented the start of a multiracial democracy.

“There’s almost a reversal in the historical relationship,” says Vinson. “Now it’s African Americans looking up to black South Africans like Mandela, people who fought to overturn the worst racial domination in world since Nazi Germany and could replace it with a democratic, non-racial society. Mandela becomes this great example for what African-Americans could possibly do. We in America are still trying to work with the idea of multiracial democracy.”

Of course, the end of apartheid didn’t mean the end of racial problems. The transatlantic dialogue on how to work through them continues — Obama has played a major part in that effort, from the Mandela Washington Fellowship for Young African Leaders started by his administration’s State Department in 2014 to this week’s series of workshops and leadership trainings for more than 200 promising young people. And, as a former anti-apartheid activist who became the first African American President of the United States, he is himself an embodiment of this history.

“There’s a struggle going on!” he said in that first 1981 speech. “It’s happening an ocean away. But it’s a struggle that touches each and every one of us. Whether we know it or not.”