The South was smoldering. A victory for the Union forces was just a few months away. Behind the Union, however, was something it wasn’t quite ready to deal with.

Thousands of former slaves trailed Gen. William T. Sherman’s army as it rampaged through Georgia, confiscating plantations and setting the countryside ablaze. The slaves had been unchained by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, but they had nothing but their freedom: no land, no jobs, no prospects. Some were famished and sick, and all were refugees. What to do with them?

On Jan. 12, 1865, Sherman convened 20 Black leaders in Savannah and, according to the minutes of the meeting, asked them to “State in what manner you think you can take care of yourselves, and how can you best assist the Government in maintaining your freedom.” Their spokesman, Garrison Frazier, a 67-year-old former slave who had bought his own freedom eight years before, argued for land, which they could “turn” and “till … and soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare.”

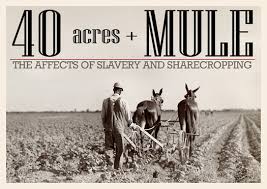

A few days later came Sherman’s Field Order No. 15: The government would set aside 400,000 acres of coastal land, divided into 40-acre plots, for the freedmen’s resettlement. Former slaveholders need not apply; the order stipulated that “no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside.” Though the order didn’t mention mules, some freedmen did receive them. No one would have used the word “reparations” back then, but many freedmen took the order to mean they were the landowners in perpetuity and began to plant and build.

Supporters argued that land redistribution was practical — it helped employ former slaves productively — and also helped balance the moral ledger. After all, slaveholders had unjustly benefited from centuries of unpaid labor, while the slaves themselves had never gotten anything from it. Critics argued that the scheme was too harsh on the planters, and warned redistribution would promote instability and obstruct peacemaking between the North and the South.

At any rate, the 40-acres plan was short-lived. Less than three months after Sherman’s order, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln, and Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, effectively rescinded the order. Tens of thousands of freedmen were forcibly evicted, their land redistributed among the white Southern planter class. Some whites were uncomfortable taking back the land, including one government official who had attended the Savannah meeting. (“I consider that the faith of the Government is solemnly pledged to these people, who have been faithful to it, and that we have no right now to dispossess them of their lands,” he wrote.) But most former slaves and Blacks in the South ended up either buying small, low-quality plots or working as sharecroppers. The deal was bad: Sell your crops to the owners at a fixed rate.

Those few months could have been one of American history’s inflection points, a moment when the government might have intervened to prevent the country from lapsing into old patterns. What happened instead was “symbolic” of wider federal government inaction, says Florida Atlantic University historian Evan Bennett. And while the issue of reparations for slavery have echoed through American history since, they’ve done so faintly. “If we were in a position where reparations could be enacted, we wouldn’t need reparations,” says Eric Foner, a historian at Columbia University who studies the Reconstruction.

Every year since 1989, Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., has proposed a bill to study the impact of slavery and potential remedies. It has never passed.