As the coronavirus pandemic grew increasingly deadly, a long list of countries imposed strict social distancing measures. Major cities all around the world, from Madrid to Paris to San Francisco, are largely shut down. Yet exactly how governments have carried out social distancing requirements has varied from country to country; the government of Mainland China has been accused of authoritarian, heavy-handed tactics, while the liberal democracies of Spain and Italy have been characterized in countless media reports as acting out of compassion — not authoritarianism. And American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) attorney Ahilan Arulanantha, in a piece for Just Security, reflects on the ways in which different governments have responded to the pandemic.

The United States, so far, has not issued a federal state-at-home order, although most of the 50 states now have stay-at-home orders at the state level. A stay-at-home order in New York State or California doesn’t mean that Americans can’t leave their homes for activities deemed essential, such as visiting a supermarket or pharmacy. But Arulanantha, who serves as senior counsel for the Southern California ACLU, describes the Sri Lankan government as being heavy-handed.

“While the coronavirus is no doubt frightening,” Arulanantha explains, “so too is massive state power wielded in the name of emergency. I recently felt that power in a very real way, because when the coronavirus pandemic arose, I was on sabbatical in Sri Lanka with my family — including my father, a physician. The government there responded by imposing a military curfew, which we lived under for a week before we managed to get out. Authorities arrested several thousand people simply for leaving their homes. Bunkered down in our rented house, we worried about whether we had enough food to last until the curfew lifted.”

Arulanantha adds, “On the afternoon we returned to California, I went for a walk with my family — without fearing arrest — for the first time in days. I have never felt the difference between life here and there so viscerally.”

The ACLU attorney goes on to say of the U.S., “Could the federal government or a state impose a Sri Lankan-style lockdown to stop the pandemic? Could the courts be excluded from overseeing such emergency action?”

Arulanantha goes on to weigh the types of powers the federal government in the U.S. can, under its constitution, enforce during an emergency.

“Given the physical and economic devastation that the virus has already created,” Arulanantha notes, “it seems obvious that the federal government has authority to impose public health measures nationwide. Even in distant regions — think rural North Dakota — where the virus has not (yet) come, if public health experts believe that residents would risk the health of themselves and their neighbors by failing to comply with a lockdown order, the courts would likely defer to that judgment, as they should.”

Arulanantha gets into specifics, noting the differences between social distancing in California under Gov. Gavin Newsom and social distancing in Sri Lanka.

“The government plainly can order social distancing in at least many parts of the country to prevent a catastrophic breakdown of health care systems, but there is more than one way to impose a lockdown,” Arulanantha observes. “For example, shelter-in-place orders like the one I am presently living under in California restrain liberty far less than the curfew order preventing people from leaving their homes in Sri Lanka, which prohibits people from even taking walks that doctors say are good for public health. Similarly, an order closing all businesses — including those providing food — could present serious constitutional concerns, particularly for those who might reasonably doubt whether the government’s food truck will make it to their house.”

One government that Arulanantha doesn’t mention is in his article is the Hungarian government under the far-right President Viktor Orbán, who is being slammed by civil libertarians around the world for using the coronavirus pandemic as an excuse to end parliamentary checks and balances in his country and give himself absolutely power. Orbán’s power grab is a textbook example of the type of civil liberty concerns that Arulanantha’s article raises.

Arulanantha wraps up the Just Security article by stressing, in essence, that social distancing needn’t come at the expense of civil liberties.

“No one should underestimate the danger of this pandemic, but neither should we underestimate the threat to our liberty arising from the government’s response,” Arulanantha asserts. “While other countries may slide into martial law or worse in this time, we can respond to coronavirus without destroying the precious freedom we enjoy in this country.”

This article was originally published by AlterNet.

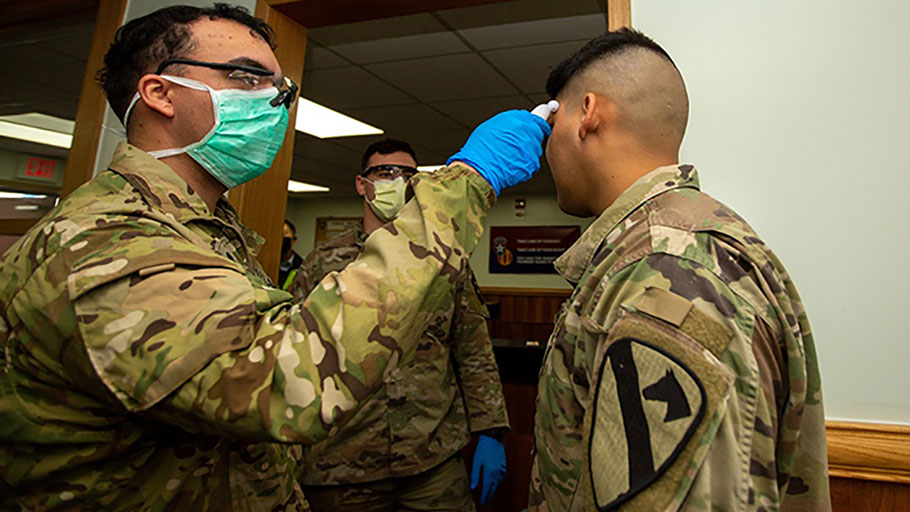

Featured image: Soldiers at US Army Garrison Casey in South Korea screen people awaiting entry to the installation, February 26, 2020. Army photo by Sgt. Amber I. Smith