Tami Thomas-Pinkney with her daughter Trinity Handy on their front lawn in Port Arthur, Texas, across from one of the city’s temporary dumpsites. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

By Julie Dermansky —

Tami Thomas-Pinkney’s house in Port Arthur, Texas, was not damaged when Hurricane Harvey soaked the city with up to 28 inches of rain on August 29. But now, a month and a half after the storm, she is preparing to move. Across the street from her family’s home is a temporary dumpsite for storm debris, which she says is endangering her family’s health and making her home unlivable.

Countless trucks haul the debris — ruined building material ripped from storm-damaged homes and household belongings previously submerged in floodwater but now covered with mold — past her house. Each day they rattle down the streets around Thomas-Pinkney, dumping their loads about a hundred feet from her front porch.

She understands that after a disaster like Harvey, the city has to do something with the debris but is outraged that officials think it’s acceptable to dump it so close to a predominantly low-income African American neighborhood with a large elderly population.

Hurricane debris lining a street in Port Arthur, Texas, on October 12, 2017. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Debris from Hurricane Harvey sat in front of a church in Port Arthur, Texas, on September 22, 2017, but has now been removed. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Port Arthur Mayor Derrick Freeman said on his Facebook page that TCEQ confirmed that the temporary dump site, known as a “Debris Management Site,” is not “jeopardizing our citizens’ health.” The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) claims that if the dump site is properly managed, it is not a health hazard.

But Catherine Dinn, a lawyer with Lone Star Legal Aid, said from what she has seen on her own visit to the dump, it isn’t being managed properly. The workers aren’t wearing protective gear, and there are no platforms for spotters to monitor the debris during unloading. In addition, she said the city is not testing for airborne particles and potentially hazardous material that could leach into the ground, and she doesn’t think state regulators are either. TCEQ confirmed that it is not performing any contaminant testing at the dump.

A worker, not wearing protective gear, at the temporary dumpsite on 19th Street in Port Arthur, Texas. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

As of October 12, the agency had based its evaluations of the dump on four site visits, each lasting between 30 minutes and an hour, according to an email from TCEQ representative Brian McGovern. “Nuisance conditions were not documented during any of these visits,” McGovern wrote.

Thomas-Pinkney, who has more than 20 years of experience as a nurse, doesn’t agree. She recognizes a health hazard when she sees one. “The dust from the dump made my daughter’s asthma worse right away,” she told me when I visited on October 12. As we spoke, a plume of dust drifted in our direction, causing me to cough.

“That is what we have to deal with every day,” she said. “We all have scratchy throats and headaches now.” And though the trucks stop at night, Thomas-Pinkney can’t get much sleep. She works a night shift and is faced with nonstop noise when she tries to sleep during the day. “Isn’t that a nuisance?” she asks.

Thomas-Pinkney has no doubt asbestos is one of the contaminants in the air, something TCEQ does not deny. “Asbestos may be mixed in with the debris depending on the age of the demolition debris,” McGovern confirmed in an email.

Hilton Kelley in front of the temporary dumpsite on 19th Street in Port Arthur, Texas. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

How “Temporary?”

Environmental activist Hilton Kelley is alarmed by the debris dumpsite. He made a genuine effort to get the city to shut it down, even blocking a truck full of debris while he was there with a city councilman. The mayor said the city would look for an alternate site but ultimately has decided to keep it open.

“It is appalling what is going on in that community,” Kelley said. “It is a clear example of environmental racism.” Though TCEQ and city officials insist that the site is temporary, Kelley fears it will remain indefinitely.

Hilton Kelley walks by a makeshift relief center set up on the driveway of his restaurant Kelley’s Kitchen in downtown Port Arthur. Organizations from across the country have been sending Kelley supplies, which are available to anyone in need. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

A young storm victim gathers donated supplies at a makeshift relief center in the driveway of Kelley’s Kitchen. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Kelley has good reason to be skeptical.

Authorization to use the site as a dump will expire on December 8, according to TCEQ, but McGovern said in an email that the agency “expects that an extension may be received for this site.”

Kelley monitors the site from its perimeter frequently. “If [TCEQ] found no nuisances, they must have gone at midnight or they are lying. The trucks are tearing up the roads, making a racket, and creating a dangerous situation for the kids,” he said. Furthermore, he finds TCEQ’s claim that “no hazardous materials are being stored” at the dump ridiculous. “All of the stuff people are getting rid of is covered in mold and toxic waste, that is why they are dumping it,” he said.

No Testing, No Problem?

I asked TCEQ whether it was testing for potential contaminant exposure to the community. According to McGovern, “TCEQ has not conducted any testing at this site,” and reiterated that, “These types of sites which are properly managed are not expected to pose a health risk to the community.”

By not testing for contaminants, the city and regulators are giving themselves an amount of deniability, Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist and technical director for the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, said on a recent call.

She understands the need to remove storm debris quickly. “Everyone wants that, but it shouldn’t come at the expense of a community that is already exposed to pollution,” she said. The dump is close to both Valero and Motiva refineries.

Subra has seen firsthand the negative impacts of similar temporary dump sites on African American communities in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and the Baton Rouge area after last year’s 1,000 year flood. “When you put a staging area so close, it threatens the health of the community,” she said.

In Subra’s eyes, allowing storm debris to be sorted across the street from people’s homes is a dereliction of duty. She thinks Thomas-Pinkney’s decision to move away to protect her family is prudent, but clearly not everyone can do that.

Dust in the air as debris at a temporary dumpsite on 19th Street in Port Arthur, Texas, is sorted. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Truck spraying water to mitigate dust particles in the air at a temporary dumpsite on 19th Street in Port Arthur, Texas. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

The Community In-Power and Development Association (CIDA), an organization founded by Kelley whose mission is empowering residents in low-income Port Arthur communities, is speaking out. “That community is already subjected to an inordinate amount of air pollution due to the [petrochemical] plants nearby,” CIDA’s marketing director, Michelle Smith, told me, “and with Harvey, things have gotten worse.”

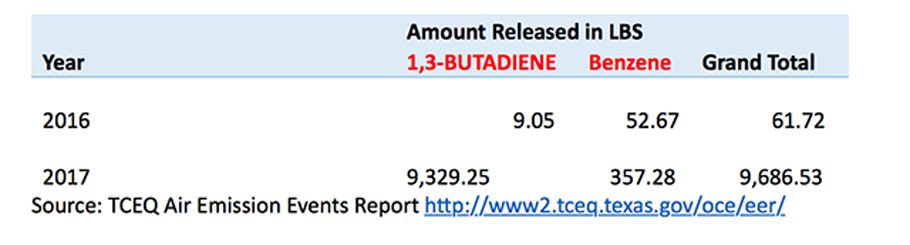

Smith analyzed TCEQ data on air quality. To quantify the increase in pollution near the dump, which is near two refineries, she looked at how much two known carcinogens, butadiene and benzene, were released between August 27 and September 19. That period reflects refinery emissions from incidents and facility shut-downs and start-ups related to Hurricane Harvey.

When Smith compared those figures with past emissions, she found a major increase. “This year the combined carcinogenic emissions [were] almost 157 times higher than the same period last year,” Smith concluded.

Those numbers are “huge,” Subra said, and are likely higher than stated because they are self-reported by industry and not verified by regulators. “Numbers like this show industry has no method of controlling emissions when hurricanes hit,” she said. Which is something, Subra thinks industry needs to fix before the next storm hits.

Those numbers are “huge,” Subra said, and are likely higher than stated because they are self-reported by industry and not verified by regulators. “Numbers like this show industry has no method of controlling emissions when hurricanes hit,” she said. Which is something, Subra thinks industry needs to fix before the next storm hits.

Issues of Environmental Justice

Members of Lone Star Legal Aid, including Dinn, met with City of Port Arthur representatives on October 12 to ask the city to continue searching for an alternate location for the dump. “City representatives stressed the dump site is temporary, and that no other site was available,” Dinn told me.

The legal organization outlined its concerns in a letter before its meeting with officials, pointing out that the neighborhood next to the dump already faces disproportionate environmental burdens and public health hazards from nearby refineries.

The letter questions whether the city’s planning staff has fully considered the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines for such sites that “include not subjecting minority or low-income populations to the adverse impacts a dump would create in accordance with Executive Order 12898.”

The EPA guidelines “requires federal agencies (or any local government or governmental agency in receipt of federal funding from a source such as FEMA) to evaluate its actions for disproportionately high and adverse effects on minority or low-income populations and to find ways to avoid or minimize these adverse impacts where possible.”

Home across the street from a temporary dumpsite on 19th Street in Port Arthur, Texas. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Dinn hopes the city will move the site, but short of that, her group will pressure the city to follow a list of guidelines to protect the community. “To do no testing at all is negligent,” Dinn said.

The recommendations include that the city “conduct air monitoring on an ongoing basis for volatiles and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas.” The letter points out the area’s high numbers of children and elderly, along with their vulnerability to these pollutants.

Dinn doesn’t expect help from EPA’s environmental justice office since its chief official Mustafa Ali resigned earlier this year. In addition, she worries the Trump administration might take aim at Executive Order 12898 and may even attempt to reverse it. A leaked internal memo indicated plans to dismantle EPA’s office of environmental justice and cut grant programs for low-income and minority communities.

Thomas-Pinkney thanks God for helping her find the power to move on. Though she is relieved her family will be leaving before the end of the month, she’s concerned about the expense of moving and paying rent at a new place after living in a house that she owned. But what troubles her most of all is leaving behind extended family members, some who are elderly and rely on her help and company.

Thomas-Pinkney glanced at the dump from her front porch and swished a fly away. “That is another thing the dump has attracted, flies,” she said. “We are used to mosquitoes, but now we have flies, roaches, and possums too. We are really going to miss this place, but who would want to live next to this?”

After Hurrican Harvey, storm debris removal is ongoing in Port Arthur, Texas. Some streets have been cleared of debris but many have not. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Debris from a home flooded by Hurricane Harvey in Port Arthur on October 12, 2017. (Photo: Julie Dermansky)

Julie Dermansky is a multimedia reporter and an affiliate scholar at The Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University. Follow her on Twitter: @jsdart