Patrisse Khan-Cullors (Photo: Tristan Kallas)

By Elena Sheppard, Yahoo Lifestyle —

It was a lifetime of oppression and violence that led activist Patrisse Khan-Cullors to cofound the Black Lives Matter movement, but the catalyst was one particular instant: The moment when George Zimmerman was acquitted in the killing of Trayvon Martin.

Scouring Facebook after the decision was announced, Khan-Cullors came upon a post by her friend Alicia Garza (who went on to cofound the movement with Khan-Cullors and Opal Tometi). Garza wrote on the social media platform, “btw stop saying that we are not surprised. that’s a damn shame in itself. I continue to be surprised by how little Black lives matter. And I will continue that. stop giving up on black life. black people, I will NEVER give up on us. NEVER.”

And Khan-Cullors wrote back, “#BlackLivesMatter.”

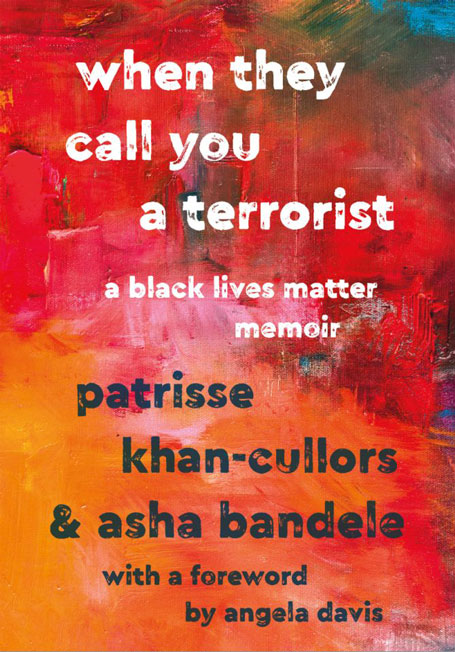

In her newly-released New York Times’ bestselling memoir, When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, which she wrote with journalist Asha Bandele, Khan-Cullors lays the hypocrisy of the American justice system out plain and simple: “I grew up in a neighborhood that was impoverished and in pain and bore all the modern-day outcomes of communities left without resources and yet supplied with tools of violence. But when someone in my neighborhood committed a crime, let alone a murder, all of us were held accountable, my God. Metal detectors, searchlights and constant police presence, full-scale sweeps of kids just walking home from school — all justified by politicians and others who said they represented our needs. Where were these representatives when white guys shot us down?”

The life Khan-Cullors lived prior to forming Black Lives Matter is the life she focuses on in the bulk of When They Call You a Terrorist. It’s an existence marked by protecting her mentally-ill brother from the LAPD, and finding her own place as a queer black woman growing up in a Jehovah’s Witness home. It’s a life defined by seeing her father struggle with drug addiction and homelessness, and her brothers treated like criminals for being black and male.

Recalling a moment she witnessed when her brothers were only 11 and 13, Khan-Cullors writes that police officers “throw them up on the wall. They make them pull their shirts up. They make them turn out their pockets. They roughly touch my brothers’ bodies.” After this, she says of her brothers, “They will be silent in the way we often hear of the silence of rape victims. They will be worried, maybe, that no one will believe them.”

Khan-Cullors spoke with Yahoo Lifestyle about her new book, America’s systems of oppression, and the importance of the Black female narrative.

When They Call You a Terrorist (St. Martin’s Press)

Yahoo Lifestyle: You write about your surprise at being approached to share your life story. Why was it important to you to overcome that feeling and share your narrative in this way?

Patrisse Khan-Cullors: When you’re socialized as a woman and raised black and poor, you’re told that your story doesn’t matter and is not worth listening to. And I think when a really important publisher said, “I think you have a story in you,” it made me nervous. I felt like, really? Why me? I had to really question: Does it make sense for me to be that person to write a book? What we’re really trying to do with the memoir, which is why we say, “a Black Live’s Matter Memoir,” is let this inspire more folk — who are a part of the Black Lives Matter movement and have been raised in different parts of the world — to talk about how blackness has shaped them, how race has shaped them. Then this book doesn’t just become a hero’s journey, it becomes a book that can be used to have hundreds and thousands of conversations with different Black people who have experienced similar issues.

What did you learn, through your writing, about yourself, your own personal experience, and the general experience of Black Americans?

I think there was a certain point in the book when I realized I grew up in a war zone — that the experience of being in a neighborhood that was consistently patrolled by law enforcement and consistently hyper criminalized…wasn’t normal. It wasn’t healthy, and so many of us experienced the impact of state violence in our communities. I had to really come to terms… with the idea that my family deserved dignity and deserved care and they deserved for their humanity to be really seen and that it wasn’t. In fact, our poverty was weaponized against us.

I wanted to talk to you about the word “terrorist” and how it is used as a weapon. Why was it important for you to reclaim that word and have it in the title of your book?

That’s a good question, because I think when some people read it they think, “Oh yeah, Black Lives Matter has been called a terrorist organization.” But I’m actually trying to have a larger conversation about how Black people who fight for our freedom are often called terrorists when actually government agencies are terrorizing Black people. There’s a reason why Angela Davis is the person who I asked to do the forward of this book, because Angela herself was on the FBI’s fugitive list and was also labeled a terrorist for fighting for Black people’s rights. This becomes a central theme.

What do you want people to learn in reading your book, particularly white people, straight people, people who haven’t had similar histories or experiences to yours?

I want people to see the real human impact of incarceration and state violence. I want them to hear the pain and suffering of Black people, but more importantly, I want them to get involved. I want them to dedicate themselves to stopping these injustices and to realizing that it’s going to take all of us to end police violence, to end state violence. It’s going to take all of us to really and truly see a world where Black lives actually matter.

In terms of getting involved: There are so many societal problems, it’s overwhelming, and it’s hard to know where to begin. I feel like there is a resistance to doing anything because people are overwhelmed and scared. How do you overcome that and become a part of the solution?

People should join an organization. There are hundreds of organizations doing amazing things across the country. Black Lives Matter is an organization, there are other civil rights organizations. You can’t do it alone. Of course it’s overwhelming. Whatever you feel is a necessary fight in your community, that’s where you find something, that’s where you find your organization, and that’s what I would encourage people to do.

In the book you talk about your anger in your erasure from the Black Lives Matter story. Why do you think that that happened, and why did it upset you?

I think we live in a culture that really sees the only Black people that deserve visibility are Black men. We’ve created a superhero of MLK, and we’ve created his legacy to be fully about him versus about hundreds of people who stood up for civil rights for Black people. I think that part of this generation is challenging the idea of who’s supposed to be at the helm of a movement, and what I try to tell people is that Black women have always been at the helm of movements. We’ve always been changing — whether that’s abolishing slavery, Black Codes, Jim Crow, the suffrage movement. We have been so pivotal and instructive and we often don’t get the visibility. I think this time around many of us are not allowing the conversation to just center around Black men’s leadership.

Honorees Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Opal Tometi, and Alicia Garza pose with an award during Glamour Women of the Year 2016 at NeueHouse Hollywood in 2016. (Photo: Frazer Harrison, Getty Images for Glamour)

So I take it from that answer that you’re not surprised at all that Black women are standing on the front lines of justice right now?

Oh yeah, no. We’ve always done that, that’s been reality, that’s what I see. And I think formally, Black women have always been social justice warriors, but also informally. My mother was the one who really taught me how to fight for people, and she wouldn’t consider herself someone in a movement. I think that’s very powerful.

What are your thoughts on all of the Oprah 2020 chatter? (Editor’s note: This interview occurred before Oprah announced that she would not be running.)

I don’t care or not. I think it’s a fun conversation to have. If she were to run, that would be really interesting. But more importantly, we have to be really careful about having one person as our savior. Oprah’s not going to fix five centuries of racism. Oprah’s not going to be able to undo corporation relationships with elected officials. So, what’s more interesting to me is how do we build a strong movement — a movement that can actually build power, and build electoral power across the country?

You have a young son, who is still a baby. How will you ready him for the world and what America looks like today?

That’s a great question. I think about it every day. I think just being a model. You can talk to someone until your face is blue and they can do whatever they want. So just being a model for what I believe is possible for Black people. Being a proud feminist and reminding him — if he decides to be a boy — that he can be a feminist, too. I’m creating spaces and structure where he gets to be curious about his life and imagine a life that isn’t just about hyper-violence and criminalization.