On September 5, at the opening of its Bicentennial observance, Harvard Law School unveiled a memorial to the enslaved people whose labor helped make possible the founding of the school.

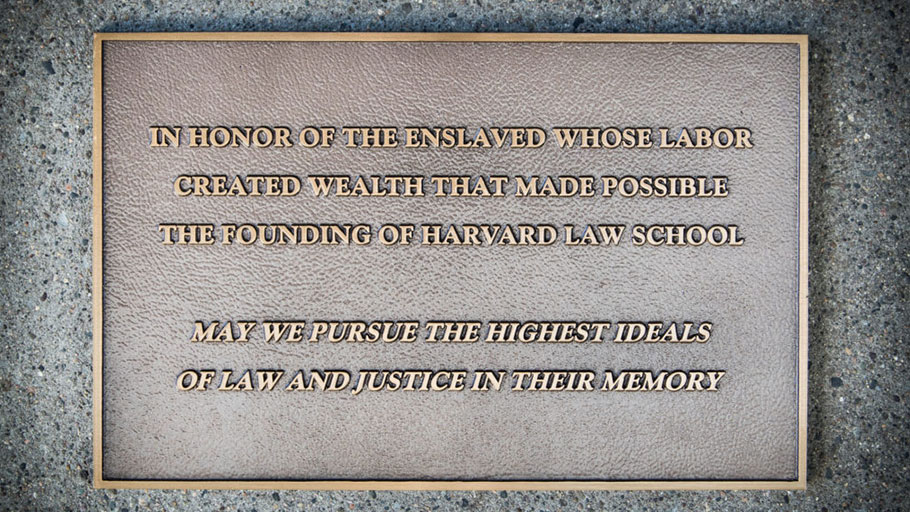

The plaque, affixed to a large stone memorial placed at the Crossroads in the center of the Law School’s plaza, reads:

In honor of the enslaved whose labor

created wealth that made possible

the founding of Harvard Law SchoolMay we pursue the highest ideals

of law and justice in their memory

Harvard Law School was founded in 1817, with a bequest from Isaac Royall, Jr. Royall’s wealth was derived from the labor of enslaved people on a sugar plantation he owned on the island of Antigua and on farms he owned in Massachusetts.

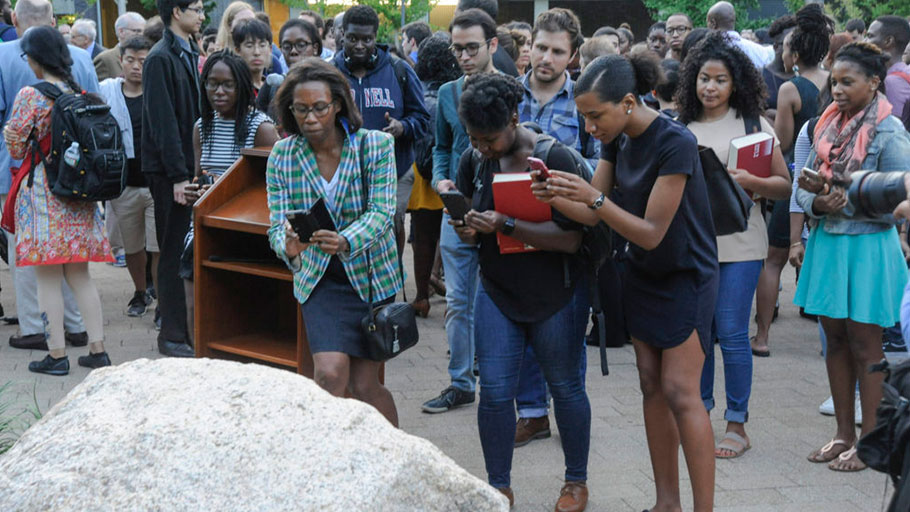

“We have placed this memorial here, in the campus crossroads, at the center of the school, where everyone travels, where it cannot be missed,” said John F. Manning, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Harvard Law School. Speaking to a gathering of more than 300 students, faculty and staff, he said: “Our school was founded with wealth generated though the profoundly immoral institution of slavery. We should not hide that fact nor hide from it. We can and should be proud of many things this school has contributed to the world. But to be true to our complicated history, we must also shine a light on what we are not proud of.” Manning expressed the hope that “the memory of those we honor today” would “inspire us to work to make law here, and throughout the world, an instrument for freedom, equality, democracy, and human dignity.”

Harvard University President Drew Faust, Professor Annette Gordon-Reed, and Royall Professor of Law Janet Halley also spoke at the unveiling at the Crossroads.

Faust said she was grateful to be at the ceremony to acknowledge “the essential contributions of enslaved people to the history of our university community and to also underscore the work of Harvard Law School to uncover and memorialize the contributions.”

Credit: Jon Chase

“Slavery is an aspect of Harvard’s past that has very rarely been acknowledged,” Faust said. “The presence and the contributions of people of African descent at Harvard are stories that have been mostly left untold. We must change that reality. As we acknowledge here today, Harvard along with many other institutions in New England was directly complicit in America’s system of racial bondage.”

Faust concluded her remarks by thanking Dean Martha Minow, Dean Manning and the HLS faculty and students for committing HLS to the continued exploration of its past. “How fitting that you should begin your bicentennial with this ceremony reminding us that the path toward justice is neither smooth nor straight,” she said.

The Law School commissioned the memorial this past summer. The inscription was drafted by Gordon-Reed, the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at Harvard Law School and Professor of History on the Harvard Faculty of Arts & Sciences, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family.”

Gordon-Reed observed that memorials usually name people. In this instance, she said, we will never know the names of all the Africans enslaved in Antigua whose labor created wealth that helped start the Law School. “The words [inscribed on the plaque] are designed to invoke all of their spirits and bring them into our minds and our memories with the hope that it will spur us to try to bring to the world what was not given to them: the laws protection and regard, and justice.”

As Manning noted, the memorial is situated on the HLS campus crossroads—a central location and outdoor gathering place between the historic Langdell Law Library, the Harkness Commons dining facility, and the Wasserstein Caspersen Clinical building.

Credit: Jon Chase

Halley read aloud the known names of enslaved men, women, and children of the Royall household from records that have survived, “so that we can all share together the shock of the sheer number knowing that this list is a fraction of the total number of the people owned by the Royall family, and a brief shared experience of their loss.” She noted that many of the names—just first names, with no last names—were probably not the original names that had been given to these individuals at birth.

“These names then are the tattered ruined remains, the accidents of recording, and the encrustation of a system that sought to convert human beings into property,” Halley said. “But they’re our tattered ruined remains, and I thought I would devote my remarks to reading them out.”

The ceremony followed a bicentennial lecture entitled The History of Harvard Law School by Dan Coquillette, the Charles Warren Visiting Professor of American Legal History at HLS, and a panel discussion with Professor Gordon-Reed; Professor Halley; Randall Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law; and Bruce Mann, the Carl F. Schipper, Jr. Professor of Law.