At a once-segregated base in heart of the Confederacy, four of America’s first black Marines were finally recognized with one of our highest civilian honors.

By James LaPorta —

CAMP JOHNSON, North Carolina—As Americans debated the Confederate names inscribed on monuments and U.S. military installations in the wake of neo-Nazi violence a few hours north in Charlottesville, four U.S. Marines who helped break the Corps’ color barrier here 75 years ago were being posthumously honored.

Among the Chinese Pistache trees, 20,000 gold stars—each symbolizing a brother-in-arms—and the sound of MV-22 Osprey helicopters cutting through the overcast skies above Onslow County, active-duty service members, veterans, and family members came together in late August to honor these “Montford Pointers,” as they are called, with the highest civilian award bestowed by Congress—the Congressional Gold Medal.

“Twenty-thousand African Americans became Marines at Montford Point,” retired Marine Chief Warrant Officer 5 Houston T. Shinal told The Daily Beast. “And we’ve probably only given out around 600 [medals] since 2011.”

The families of Joseph Orthello Johnson, of Leesburg, Virginia; Virgil W. Johnson, of Woodbridge, Virginia; John Thomas Robinson, of Ypsilanti, Michigan; and Leroy Lee, Sr., of Augusta, Georgia, accepted the medal that was order in 2011 by then President Barack Obama, in recognition of the contributions made by Montford Point Marines to the Marine Corps and the U.S. from 1942 to 1949, during a time when they were not wanted in uniform at all.

The Montford Point Marines Association has identified the names of about 1,200 former Montford Pointers; as of this month, just 300 of those are still alive.

There’s an old lesson to be learned from these veterans—of valor that most Americans have never heard of, of pride and defiance that would drive young black Americans to earn the title of Marine in the face of bigotry and exclusion.

On the eve of the U.S. entering World War II, just months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 executive order would establish the Fair Employment Practices Commission and open the door to “full participation in the defense program by all persons regardless of color, race, creed, or national origin.”

The Marine Corps’ 17th commandant, Gen. Thomas Holcomb, a legend in his own right as the first Marine to achieve the rank of four-star general, and himself a recipient of the Navy Cross—the nation’s second highest award for combat service—was staunchly against Roosevelt’s aim to desegregate the armed forces.

Holcomb would testify to Congress in May 1941 and again in January 1942, just a month after Pearl Harbor, that “if it were a question on having a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 Negroes, I would rather have the whites.” Asserting that black Americans in uniform would be an unsound tactical decision, he told lawmakers there would be “a definite loss of efficiency in the Marine Corps if we have to take Negroes.”

However, with war efforts ramping up and political pressure coming from the White House, the Marine Corps would eventually adhere to Roosevelt’s executive order and start enlisting black Americans in June 1942.

For the first time since the Revolutionary War, 900 black recruits between the ages of 19 and 29 would answer the nation’s call to service.

Yet, despite the presidential mandate to the Defense Department to “lead the way in erasing discrimination over color or race,” the Corps outlined that these unwanted Americans would not be allowed at the two training bases that transform civilians into Marines—Recruit Depot in San Diego and Parris Island in South Carolina.

Instead, these black recruits would be sent to an undeveloped piece of land known as Montford Point, on the outskirts of Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. Today, it’s named Camp Johnson, after Montford Point drill instructor Sgt. Maj. Gilbert “Hashmark” Johnson, so named for having more service stripes than rank stripes after having previously served in the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy. (Johnson retired in 1959 after 32 years of service; he died in 1972.)

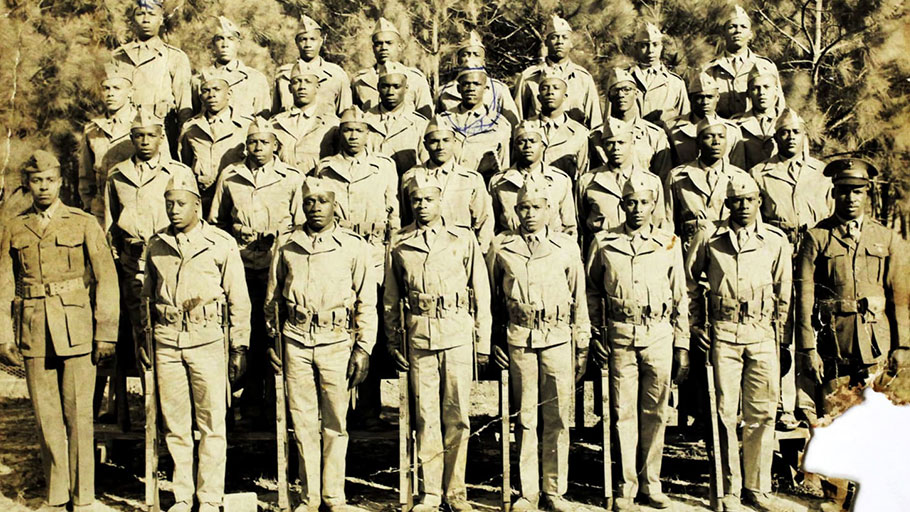

PHOTOQUEST/GETTY. A platoon of African American ‘boot recruits’ listen to their drill instructor whose job is to turn them into finished Marines, at Montford Point Camp, in North Carolina, April 1943.

The military would stamp “Colored” on the service-record books and on the enlistment contracts of black Americans entering military service, according to the History and Museums Division of the Marine Corps.

Former Sgt. Leroy Pittman, 85, still remembers when he arrived at Montford Point in June 1948, after dropping out of high school in Hartford, Connecticut. He told this reporter last year, writing for The Washington Post that, “It was tough. We had to build our own huts to live in. We spent weeks chopping down trees and dodging rattlesnakes. It wasn’t a joke.”

Marine veteran Leroy Lee Jr., who accepted the medal on behalf his father, Gunnery Sgt. Leroy Lee Sr., told The Daily Beast that his father came off the farm and was drafted into the Marines. “When he came into the Marine Corps, he was determined to be the best,” Lee Jr. said.

Initially, there were no black drill instructors at Montford Point. The recruits, like today’s military boot camps, were organized into 30-man platoons—with white drill instructors.

“When [the Marine Corps] made a change over from the white drill instructors to black drill instructors, when Sgt. Maj. Edgar Huff and Sgt. Maj. Gilbert Johnson came on, [the recruits] thought it was going to be easier, but it got rougher, because they wanted them to be just as good or better than any other Marine to hold that title,” Lee Jr. said.

Outside of Montford Point, in the city of Jacksonville, the Marines faced discrimination because of the color of their skin, despite the uniform they wore. A sign that read, “No Blacks on this side of town,” welcomed new recruits getting off the train to report for training.

Pittman said they were not allowed to ride in cars or go into town to eat. Harassment or arrest without cause was frequent from the Jacksonville Police Department, with locals threatening the black Marines to “not cross the railroad tracks in Jacksonville,” and Montford Point Marines needing to access nearby Camp Lejeune could only do so if accompanied by a white Marine.

They knew the deck was stacked against them, not just from a military perspective, but from a society that looked upon them with disdain. Their response was to be resolute in character and in the the face of exclusion.

“To steal a phrase from Dr. King, you judge people by the content of their character, not the color of their skin and my father always emphasized that to me, my brothers, and my sister and it always stuck with me when I had to go through those same racial issues as a child of the ’50s and ’60s. It helped me be strong to deal with those issues,” Lee Jr. said.

The Montford Point Marines would go on to serve in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Earlier this year, retired 1st Sgt. Barnett Person, a 1946 Montford Point grad, passed away at the age of 86. He told this reporter last year that, “We wanted to be the best.… We didn’t see color.… We just wanted to be Marines, to serve our country and our fellow brothers during a time of war, [regardless] if those Marines were white or black.” Person would serve in Korea and Vietnam and in July 1967, he would save the life of a fellow Montford Pointer, retired 1st Sgt. Jack McDowell.

At the time, Person was a gunnery sergeant and a tank commander with the 3rd Tank Battalion out of Twentynine Palms, California. Between July 18 and 19 of 1967, McDowell’s company came under heavy small-arms fire, mortar and artillery bombardment.

“We lost seven Marines that day. We had many wounded,” said McDowell, who was then the senior enlisted Marine for Golf Company 2nd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, an infantry unit out of Camp Lejeune.

Just as McDowell’s unit was about to be overrun by a North Vietnamese army regiment, Person would come to McDowell’s rescue, according to documents released by the Marine Corps History Division.

“I wouldn’t be alive if it wasn’t for Person,” McDowell said.

Two months before rescuing McDowell, Person’s actions in combat were recognized when he received the Silver Star, the nation’s third highest award for combat valor. He later received two Purple Hearts, one after a 50-caliber round took one of his legs.

“I think the lesson [of the Montford Point Marines] would be that you’re not bound by your circumstances. You can persevere and move beyond the present day or the present situation that you’re facing,” said Penelope Johnson Brown of Baltimore, who accepted the gold medal on behalf of her father, Joseph Orthello Johnson, and uncle, Virgil W. Johnson, alongside her sister, Joy Momon of Leesburg.

“That was exemplified by my father and my uncle throughout their entire life, they took the experience from the Montford Marines and they were able to come back to the States, continue with their education and carry those values and persevere throughout their entire life, despite the circumstances they faced at various times, so there was no limit to what they could do and they instilled that in us and in their grandchildren,” Brown said.

Brown’s daughter Ariel told The Daily Beast that, “I have always been proud of what they did and their service. When we would learn about World War II in school, I was proud to say that my grandfather and granduncle served, that they were Marines because a lot of people didn’t know that African Americans had served in that war.”

Ariel Brown said that it’s important for her generation—millennials —to know the contributions they made. “Knowing what they went through, you know the segregation and how they overcame so many barriers, that shows I can contribute to and I can make the world better me like they did.”

“We need to persevere like they did and see the good in America, that while it’s not perfect, we always need to strive to make it better.”