By Robert P. Jones

The shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, and the anger poured out in response by Ferguson’s mostly black population, has snapped the issue of race into national focus. The incident has precipitated a much larger conversation, causing many Americans to question just how far racial equality and race relations have come, even in an era of a black president and a black attorney general.

Polls since the incident demonstrate that black and white Americans see this incident very differently. A Huffington Post/YouGov poll finds that while Americans overall are divided over whether Brown’s shooting was an isolated incident (35 percent) or part of a broader pattern in the way police treat black men (39 percent), this balance of opinion dissipates when broken down by race. More than three-quarters (76 percent) of black respondents say that the shooting is part of a broader pattern, nearly double the number of whites who agree (40 percent). Similarly, a Pew Research Center poll found that overall the country is divided over whether Brown’s shooting “raises important issues about race that need to be discussed” (44 percent) or whether “the issue of race is getting more attention than it deserves” (40 percent). However, black Americans favor the former statement by a four-to-one margin (80 percent vs. 18 percent) and at more than twice the level of whites (37 percent); among whites, nearly half (47 percent) believe the issue of race is getting more attention than it deserves.

Clearly white Americans see the broader significance of Michael Brown’s death through radically different lenses than black Americans. There are myriad reasons for this divergence, from political ideologies—which, for example, place different emphases on law and order versus citizens’ rights—to fears based in racist stereotypes of young black men. But the chief obstacle to having an intelligent, or even intelligible, conversation across the racial divide is that on average white Americans live in communities that face far fewer problems and talk mostly to other white people.

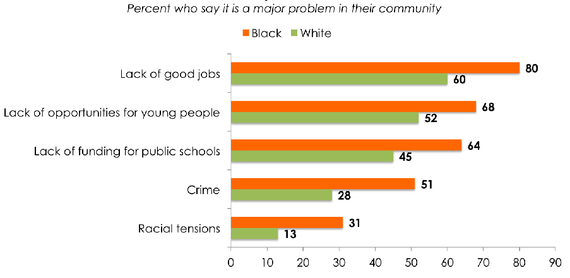

A 2012 PRRI survey found that black Americans report higher levels of problems in their communities compared to whites. Black Americans were, on average, nearly 20 percentage points more likely than white Americans to say a range of issues were major problems in their community: lack of good jobs (20 points), lack of opportunities for young people (16 points), lack of funding for public schools (19 points), crime (23 points), and racial tensions (18 points).

Disparities in Reported Community Problems, by Race

Public Religion Research Institute, Race, Class, and Culture Survey, September 2012These incongruous community contexts certainly set the stage for cultural conflict and misunderstanding, but the paucity of integrated social networks—the places where meaning is attached to experience—amplify and direct these experiences toward different ends. Drawing on techniques from social network analysis, PRRI’s 2013 American Values Survey asked respondents to identify as many as seven people with whom they had discussed important matters in the six months prior to the survey. The results reveal just how segregated white social circles are.

Public Religion Research Institute, Race, Class, and Culture Survey, September 2012These incongruous community contexts certainly set the stage for cultural conflict and misunderstanding, but the paucity of integrated social networks—the places where meaning is attached to experience—amplify and direct these experiences toward different ends. Drawing on techniques from social network analysis, PRRI’s 2013 American Values Survey asked respondents to identify as many as seven people with whom they had discussed important matters in the six months prior to the survey. The results reveal just how segregated white social circles are.

Overall, the social networks of whites are a remarkable 93 percent white. White American social networks are only one percent black, one percent Hispanic, one percent Asian or Pacific Islander, one percent mixed race, and one percent other race. In fact, fully three-quarters (75 percent) of whites have entirely white social networks without any minority presence. This level of social-network racial homogeneity among whites is significantly higher than among black Americans (65 percent) or Hispanic Americans (46 percent).

Racial and Ethnic Makeup of White Social Networks

PRRI, American Values Survey, 2013For me, a white man, hearing accounts of how black parents teach their sons to deal with police is difficult to grasp as reality. Jonathan Capehart’s Washington Post column after the Brown shooting contained a personal and poignant account of his mother’s lessons to him as a young black man:

PRRI, American Values Survey, 2013For me, a white man, hearing accounts of how black parents teach their sons to deal with police is difficult to grasp as reality. Jonathan Capehart’s Washington Post column after the Brown shooting contained a personal and poignant account of his mother’s lessons to him as a young black man:

How I shouldn’t run in public, lest I arouse undue suspicion. How I most definitely should not run with anything in my hands, lest anyone think I stole something. The lesson included not talking back to the police, lest you give them a reason to take you to jail—or worse. And I was taught to never, ever leave home without identification.

And national survey data suggests that the need for this kind of parental coaching persists in the black community today. When given a choice between two traits that respondents believe their child should have, a 2012 PRRI survey found that African Americans are far more likely than white Americans to favor “obedience” over “self-reliance.” By a margin of three to one (75 percent to 25 percent), African Americans preferred “obedience” to “self-reliance;” among white Americans, only 41 percent preferred “obedience,” compared to 59 percent who preferred “self-reliance.”

In discussing these survey findings during a panel discussion, Michael McBride, an African-American pastor who directs Lifelines to Healing, a campaign to prevent neighborhood violence, related his personal story of being beaten by two white police officers in March 1999. He described it this way:

This happened because they felt like I was not being obedient enough. The way they saw the world and me in their world created a certain kind of fear and reaction to my actions that caused me harm. I live with that experience as many folks of color live with that experience.

But these are not stories most whites are socially positioned to hear. Widespread social separation is the root of divergent reactions along racial lines to events such as the Watts riots, the O.J. Simpson verdict, and, more recently, the shootings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. For most white Americans, #hoodies and #handsupdontshoot and the images that have accompanied these hashtags on social media may feel alien and off-putting given their communal contexts and social networks.

If perplexed whites want help understanding the present unrest in Ferguson, nearly all will need to travel well beyond their current social circles.