Is the country more or less racist? How can the percentage of people holding anti-black attitudes have increased from 2006 to 2008 at a time when Obama performed better among white voters than the two previous white Democratic nominees, and then again from 2008 to 2012 when Obama won a second term? In fact, the shifts described by Tesler and Pasek are an integral aspect of the intensifying conservatism within the right wing of the Republican Party.

Thomas B. Edsall, New York Times —

Although there was plenty of discussion during the 2012 presidential campaign about the Hispanic vote and how intense black turnout would be, the press was preoccupied with the white vote: the white working class, white women and upscale whites.

Largely missing from daily news stories were references to research on how racial attitudes have changed under Obama, the nation’s first black president. In fact, there has been an interesting exploration of this subject among academics, but before getting to that, let’s look back at some election results.

In the 16 presidential elections between 1952 and 2012, only one Democratic candidate, Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, won a majority of the white vote. There have been nine Democratic presidential nominees who received a smaller percentage of the white vote than Obama did in 2008 (43 percent) and four who received less white support than Obama did in 2012 (39 percent).

In 2012, Obama won 39 percent of the white electorate. Four decades earlier, in 1972, George McGovern received a record-setting low of the ballots cast by whites, 31 percent. In 1968, Hubert Humphrey won 36 percent of the white vote; in 1980, Jimmy Carter got 33 percent; in 1984, Walter Mondale took 35 percent of the ballots cast by whites. As far back as 1956, Adlai Stevenson tied Obama’s 39 percent, and in 1952, Stevenson received 40 percent – both times running against Dwight D. Eisenhower. Two Democratic nominees from Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis in 1988 (40 percent) and John Kerry in 2004 (41 percent), got white margins only slightly higher than Obama’s in 2012 – and worse than Obama’s 43 percent in 2008. In other words, Obama’s track record with white voters is not very different from that of other Democratic candidates.

Ballots cast for House candidates provide another measure of white partisanship. These contests have been tracked in exit polls from 1980 onward. Between 1980 and 1992, the white vote for Democratic House candidates averaged 49.6 percent. It dropped sharply in 1994 when Newt Gingrich orchestrated the Republican take-over of the House, averaging just 42.7 percent from 1994 through 2004. White support for Democrats rose to an average of 46.7 percent in 2006 and 2008 as public disapproval of George W. Bush and of Republicans in Congress sharply increased.

How can the percentage of people holding anti-black attitudes have increased from 2006 to 2008 at a time when Obama performed better among white voters than the two previous white Democratic nominees, and then again from 2008 to 2012 when Obama won a second term?

In the aftermath of Obama’s election, white support for Congressional Democrats collapsed to its lowest level in the history of House exit polling, 38 percent in 2010 – at once driving and driven by the emerging Tea Party. In 2012, white Democratic support for House candidates remained weak at 39 percent.

Despite how controversial it has been to talk about race, researchers have gathered a substantial amount of information on the opinions of white American voters.

The political scientists Michael Tesler of Brown University and David O. Sears of UCLA have published several studies on this theme and they have also written a book, “Obama’s Race: The 2008 Election and the Dream of a Post-Racial America,” that analyzes changes in racial attitudes since Obama became the Democratic nominee in 2008.

In their 2010 paper, “President Obama and the Growing Polarization of Partisan Attachments by Racial Attitudes and Race,” Tesler and Sears argue that the

evidence strongly suggests that party attachments have become increasingly polarized by both racial attitudes and race as a result of Obama’s rise to prominence within the Democratic Party.

Specifically, Tesler and Sears found that voters high on a racial-resentment scale moved one notch toward intensification of partisanship within the Republican Party on a seven-point scale from strong Democrat through independent to strong Republican.

To measure racial resentment, which Tesler and Sears describe as “subtle hostility towards African-Americans,” the authors used data from the American National Election Studies and the General Social Survey, an extensive collection of polling data maintained at the University of Chicago.

In the case of A.N.E.S. data, Tesler and Sears write:

The scale was constructed from how strongly respondents agreed or disagreed with the following assertions: 1) Irish, Italian, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors. 2) Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class. 3) Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve. 4) It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.

The General Social Survey included questions asking respondents to rate competing causes of racial discrimination and inequality:

The scale was constructed from responses to the following 4 items: 1) Irish, Italian, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors. 2) A 3-category variable indicating whether respondents said lack of motivation is or is not a reason for racial inequality. 3) A 3-category variable indicating whether respondents said discrimination is or is not a reason for racial inequality. 4) A three-category variable indicating whether respondents rated whites more, less or equally hardworking than blacks on 7 point stereotype scales.

Supporting the Tesler-Sears findings, Josh Pasek, a professor in the communication studies department at the University of Michigan, Jon A. Krosnick, a political scientist at Stanford, and Trevor Tompson, the director of the Associated Press-National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, use responses from three different surveys in their analysis of “The Impact of Anti-Black Racism on Approval of Barack Obama’s Job Performance and on Voting in the 2012 Presidential Election.”

Pasek and his collaborators found a statistically significant increase from 2008 to 2012 in “explicit anti-black attitudes” – a measure based on questions very similar those used by Tesler and Sears for their racial-resentment scale. The percentage of voters with explicit anti-black attitudes rose from 47.6 in 2008 and 47.3 percent in 2010 to 50.9 percent in 2012.

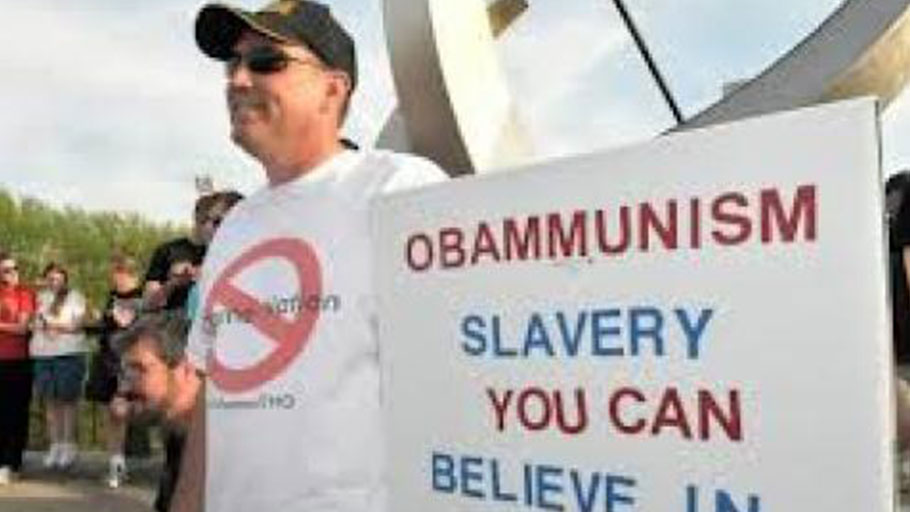

Crucially, Pasek found that Republicans drove the change: “People who identified themselves as Republicans in 2012 expressed anti-Black attitudes more often than did Republican identifiers in 2008.”

In 2008, Pasek and his collaborators note, the proportion of people expressing anti-Black attitudes was 31 percent among Democrats, 49 percent among independents, and 71 percent among Republicans. By 2012, the numbers had gone up. “The proportion of people expressing anti-Black attitudes,” they write, “was 32 percent among Democrats, 48 percent among independents, and 79 percent among Republicans.”

At the moment, the population of the United States (314 million) is heading towards a majority-minority status in 2042.

The American electorate, on the other hand (126 million) is currently 72 percent white, based on the voters who cast ballots last November.

Obama’s ascendency to the presidency means that, on race, the Rubicon has been crossed (2008) and re-crossed (2012).

What are we to make of these developments? Is the country more or less racist? How can the percentage of people holding anti-black attitudes have increased from 2006 to 2008 at a time when Obama performed better among white voters than the two previous white Democratic nominees, and then again from 2008 to 2012 when Obama won a second term?

In fact, the shifts described by Tesler and Pasek are an integral aspect of the intensifying conservatism within the right wing of the Republican Party. Many voters voicing stronger anti-black affect were already Republican. Thus, in 2012, shifts in their attitudes, while they contributed to a 4 percentage point reduction in Obama’s white support, did not result in a Romney victory.

Some Republican strategists believe the party’s deepening conservatism is scaring away voters.

“We have a choice: we can become a shrinking regional party of middle-aged and older white men, or we can fight to become a national governing party,” John Weaver, a consultant to the 2008 McCain campaign, said after Obama’s re-election. Mark McKinnon, an adviser to former President George W. Bush, made a similar point: “The party needs more tolerance, more diversity and a deeper appreciation for the concerns of the middle class.”

Not only is the right risking marginalization as its views on race have become more extreme, it is veering out of the mainstream on contraception and abortion, positions that fueled an 11 point gender gap in 2012 and a 13 point gap in 2008.

Given that a majority of the electorate will remain white for a number of years, the hurdle that the Republican Party faces is building the party’s white margins by 2 to 3 points. For Romney to have won, he needed 62 percent of the white vote, not the 59 percent he got.

Working directly against this goal is what Time Magazine recently described as the Republican “brand identity that has emerged from the stars of the conservative media ecosystem: Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Bill O’Reilly, Ann Coulter, and others.”

It is not so much Latino and black voters that the Republican Party needs. To win the White House again, it must assuage the social conscience of mainstream, moderate white voters among whom an ethos of tolerance has become normal. These voters are concerned with fairness and diversity, even as they stand to the right of center. It is there that the upcoming political battles – on the gamut of issues from race to rights – will be fought.