By Tess Raser, Truthout

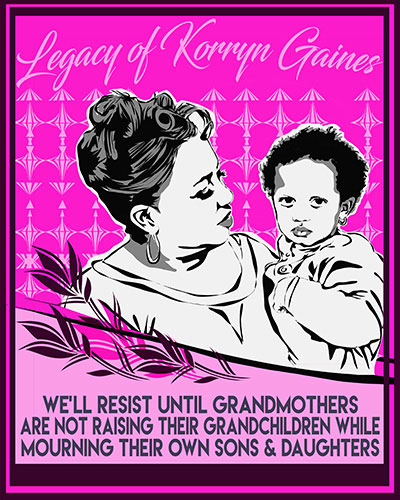

Rhanda Dormeus, the mother of the late Korryn Gaines, holds her grandchild. (Image: Kate Deciccio)

As a young Black teacher, I feel empathy for every person I hear is taken from us by state-sanctioned violence — whether through the carceral state or killed by the police. However, when I first heard that 23-year-old Korryn Gaines was killed by Baltimore County police last summer, I felt something deeper, a connection to her. Korryn was close in age to me, a few years younger, and like me, a Virgo. She was known for being outspoken and a bookworm, and also like me, she spent her high school years playing in the school band.

When I interviewed her mother, Rhanda Dormeus, I could feel her grief and rage intensely, and hear her deep love for her late daughter in her words. When Korryn died from a bullet wound from Baltimore police on August 1, 2016, Rhanda’s world was turned upside down. She described her daughter to me with bittersweet admiration.

“She could be very blunt, extremely blunt. She was very outspoken. She was just going to say what she thought was right at the time,” Rhanda said.

Korryn was born on August 24, 1992, weighing 9 pounds 14 ounces. “When she was little, she was always feisty. She could always think of something witty to say at a young age. I never had any problems out of her,” Rhanda says.

Korryn grew up with two sisters and three brothers, and as the third-oldest, she helped them grow up, too. While she lived apart from some of her siblings at times, they always stayed in touch, and Korryn always looked after them.

“That little girl did everything. She took her swimming lessons at [age] four, and was the only child to be promoted to the adult group. She wanted to go to dancing school, but she didn’t like the stretching. She realized the discipline and all that, and she wasn’t interested in all that,” Rhanda chuckles.

Korryn was an active teenager, with many friends and many activities. She played clarinet in the school marching band for two years in high school, and also was a cheerleader. “All my children really kept me busy, but she kept me busiest,” said Rhanda. “She was more of a daredevil. She wanted to try things that other people weren’t taking the chances to do.”

Korryn was eager to expose herself to plays and different types of books, and was an avid book reader. “Oh! I could buy her books on Friday, and I’d have to go buy her new books the next day,” said Rhanda, who spent much of her time at an urban bookstore in her neighborhood to purchase books for her bookworm of a daughter.

“I used to tell her to slow down! [The bookstore] had a little promotion where you can get so many books, and then get a free book. I think you had to buy 10 books, and I would get a free book every time I went because I would buy her about 10 books. And the lady knew what she liked. She would go and pull off the books that [Korryn] would like,” Rhanda said.

Rhanda laughs about how into style and hair Korryn was. “She was graduating from elementary school, and she wanted a pair of heels, and I said, ‘A pair of heels? You aren’t even 11 years old yet.’ She threw a hissy fit,” she chuckled. The two agreed on a compromise. “We found a perfect pair, and she was smiling again.”

Upon graduating from high school, Korryn attended college, and had a beautiful son, Kodi, in her first semester at Morgan State University. Kodi was the love of her life.

“She was a doting mom and a disciplinarian,” Rhanda recalled. “When Kodi was little, she would talk to him and explain to him why he couldn’t do something. She later gave birth to a beautiful daughter, Karsyn. She communicated to them on an adult level with appropriate interactions. She never handled them like ‘baby babies.’ She really would have conversations with them. It would tickle me to death.”

“That’s why my grandson, Kodi [now six], is articulate. He’s been talking a long time. She just taught her children,” Rhanda said. Korryn adored her children and would frequently post videos with them on social media. Her children now treasure those videos, according to Rhanda. Kodi turned six on May 17 and Karsyn turned two on May 9.

Although Korryn initially majored in political science, she later transferred to cosmetology school. She pursued her license in cosmetology as well. “She was very good at hair and makeup. She worked in that field, but most of her time was spent as a loving mother and daughter. She spent a lot of time at my house. We’d plan to do so many things for the summer. She was always taking the kids somewhere,” said Rhanda.

Little Karsyn got on her first plane with her mother at about four months old. Right before Korryn was murdered, she had taken the children to Disneyland. “She just did a whole bunch of stuff with them. It would be nothing for her to take the kids down to Ocean City [about a three-hour drive from Baltimore County],” Rhanda explained.

Always an avid reader and outspoken activist, Korryn became more politicized in the wake of the Baltimore police killing of Freddie Gray.

“She always was a little radical, and she was hardcore about certain stuff. She did a lot of research … laws of the land,” Rhanda said. Korryn would not only constantly read, but she would do so with the goal of educating herself and her community members. “And right after Freddie Gray got killed, it amplified because he was a neighbor to us. We used to see him.”

Gray’s death, along with the death of Tamir Rice and countless others, threw Korryn deeper into a fight to educate people to take a stand against anti-Black police killings. “It just got magnified with the rise in deaths because it was right in her own backyard. She used to always worry about my son,” Rhanda said of Korryn’s brother who, like many young Black men in their community, was harassed by the police.

Rhanda has police officers in her family, but remembers how poorly her son has been treated by Baltimore and Baltimore County police. “The things that police have done to him right in front of my eyes, and my son doesn’t get in trouble, it’s scary. [Korryn] was always afraid for her brother,” Rhanda continued.

As a spoken word artist, Korryn would express some of her growing rage in her poetry. “She had a lot of rage at the direction the world had taken. She wanted to teach what some people hadn’t [taken] time out to learn. It could be a rant, on [Facebook live], her spoken word,” Rhanda said. Korryn was very passionate about resisting police misuse of power and brutality. She had done extensive studying and at times her knowledge of the legal system would anger and intimidate police officers. “She would tell them, ‘I know you can’t do that.'”

Korryn was involved in a lawsuit against the police on behalf of her daughter Karsyn’s father. “[The police] had been harassing [Korryn] because she had a lawsuit against one of the jails down here, and she was able to get people on the phone that the average person could not get to. Karsyn’s dad was wrongfully detained [in jail], and put back into the [legal] system. There was a series of things that Korryn had investigated and actually gotten a lawyer, so she was able to go after them,” Rhanda said. Karsyn’s father was released, but the arrests stayed on his record. Korryn was involved in a lawsuit to clear his record.

One day, Korryn’s license plates were removed from her car without any explanation. When she looked into the system, there was nothing that would warrant the state taking her tags. Her insurance was legitimate, her car was registered and her record was clean. At that point, Korryn did some research and discovered that it would be legal to drive without plates if she placed free traveler tags on her car. “She drove around with those tags for a long time before they stopped her,” Rhanda said. She was stopped around the time of the lawsuit.

After Korryn returned from Disneyland with her children, she found that someone had broken into her home. She decided to legally purchase a gun for protection. Prior to the break-in, she had also had issues with someone trying to gain access to her home.

“She went and bought a shotgun because it’s just her and the kids. She said, ‘I’m not staying in here without protection,'” Rhanda explained.

Korryn never expected that she would need to protect her home from the police. But on August 1, 2016, Baltimore County police showed up at her home with a warrant for her arrest, because she had allegedly not shown up in court for the ordeal over her license plates. However, Rhanda claims that Korryn had been demanding a court date and was not given one. They had previously questioned Korryn, asking if she were part of terrorist groups and had been monitoring her social media pages, according to Rhanda.

Rhanda remembers the day clearly. It was a Monday. “The day started so weirdly because I hadn’t spoken to her since late Friday night, laughing and joking on the phone…. Monday morning, she called me and said someone tried to kick [her] door down.” Korryn soon told her mother that the police were at her home. Rhanda immediately went to Korryn’s home, and when she got to the scene, an officer took her phone.

“They took my phone and said they’d bring it back, and they were stupid because they didn’t delete [their communication from it],” Rhanda said. Officers used Rhanda’s phone to communicate with Korryn while she was inside her home with her children, apparently trying to impersonate her mother.

“They were actually typing,” Rhanda said. “Someone was responding to the texts [from my girlfriend].”

Rhanda learned this when she got home later that evening and called that friend, who was surprised to hear from Rhanda as if they hadn’t been communicating all afternoon. “They didn’t have a warrant to get my phone,” Rhanda said. “Took my phone first, got the warrant second…. They were communicating [with] Korryn.”

It would have been obvious to Korryn that it wasn’t Rhanda who was communicating with her, as they knew each other’s language so well. “She was my daughter, so she knows me, my language. The stuff they were sending to her, she had to have known that wasn’t me,” Rhanda said.

Whoever texted Korryn from Rhanda’s phone wrote, “What’s wrong with you guys, why don’t you guys just come on out?” Korryn then responded to say, “Ma, are you going crazy?” She knew that Rhanda would never have talked to her in that way.

Many hours went by, and Rhanda never got a chance to communicate with Korryn. Meanwhile, Korryn was streaming the whole situation on Facebook Live. While police initially tried to frame the events as a hostage situation or standoff, there was public evidence that Korryn was just in her home with her children, who at various points were seen on the livestream, playing and eating.

“The police allege they got a warrant to shut her page down. As soon, I mean minutes after her page went down, she was gunned down! Legal services for Facebook did get in contact with me stating they had received the request from the Baltimore County Police Department to shut her page down, but declined to disclose the time of the request,” Rhanda explained. Rhanda and Korryn were sure that the police had been monitoring her page well before the incident.

Officers had assured Rhanda that the situation was all a mistake, that they were not there for Korryn. They told Rhanda that they were at the home to arrest someone else. According to Rhanda, right before Korryn was shot, a neighbor heard Korryn state that she would come outside if they put the guns down. Immediately afterward, that neighbor heard an officer say, “I’m sick of this shit,” and promptly begin shooting.

“Officer shot through a wall and couldn’t even see nothing,” Rhanda said. She describes the sentiment of the officer as, “Nerve of this little Black girl to stay in this house when we said to come out!”

Korryn was in the line of fire. She was shot dead, and her son Kodi was also wounded. Rhanda believes this is why the police immediately requested to take down the livestream, to cover up for the fact that Kodi was clearly shot by an officer.

Rhanda had Kodi with her after Korryn was killed. “When I went to see him, I said, ‘Why is [Kodi’s] face swollen?'” The police responded that he was fine. However, it turned out that Kodi had suffered a bullet wound to his face.

“The crazy thing is, he was shot in the right elbow of the arm holding the phone. Not to mention, Kodi said they shot him purposely when he wouldn’t put the phone down! I wasn’t there, but my grandson is one intelligent little guy!” Rhanda explained.

Kodi recovered from the wound and now lives with his father. Although Rhanda rarely sees him, she says that even as he has experienced enormous grief at losing his mother, he has been conscious that others are also grieving: He checks in on Korryn’s sisters — his aunts — to see how they are doing.

Rhanda is now co-parenting Korryn’s 2-year-old daughter with Karsyn’s father, and honors Korryn by placing pictures of her around their home as a way for Karsyn to connect to her mother. “Oh my God, we have pictures everywhere. Pillowcases with her mommy’s pictures on it, she can kiss them. She says, ‘Night night,’ and says, ‘Good morning, Mommy’ in the morning,” Rhanda said. Whenever Karsyn sees a new photo of her beautiful mother, she becomes ecstatic.

Rhanda takes it day by day. “Karsyn is a highlight in my life. She’s been my lifeline. If I couldn’t get a hold of her, I would cease to exist, and I have an excellent support system, but just having a piece of [Korryn] with me all the time soothes my soul,” Rhanda said.

She sees so much of her daughter in Karsyn. When Korryn was first killed, Rhanda started to feel a dependency on Karsyn. “The first of the month, let me tell you, it’s rough for me. It’s the first of another month of my child not being with me,” said Rhanda.

Rhanda recalls an intense conversation with Korryn two weeks before she was killed, about the police. “[Korryn] said, ‘The police are going to kill me because I know too much.’ I asked her, ‘Aren’t you afraid?’ Korryn said, ‘Afraid of what? Of dying? I ain’t living if I’m afraid of dying!'” Rhanda then asked if her she was prepared to be a martyr, to which Korryn responded, “I’m prepared to die for what I believe in.”

Rhanda and her family attempted to charge officers involved in the shooting. However, on September 21, 2016, it was announced that the officers who shot Korryn would not be subject to any charges.

In her short lifetime, Korryn was opinionated and outspoken, always loving and deeply committed to her family and her people. Her mother and her children adored her.

Tess Raser is a public school teacher and organizer on Chicago’s South Side.