By Dr. Jahi Issa and Reggie Mabry

The moral case for Black reparations has effectively been made, but the legal argument has met much frustration in the courts. The authors believe that the period after 1808, when U.S. participation in the international slave trade was outlawed, is key to clearing the legal hurdles to reparations

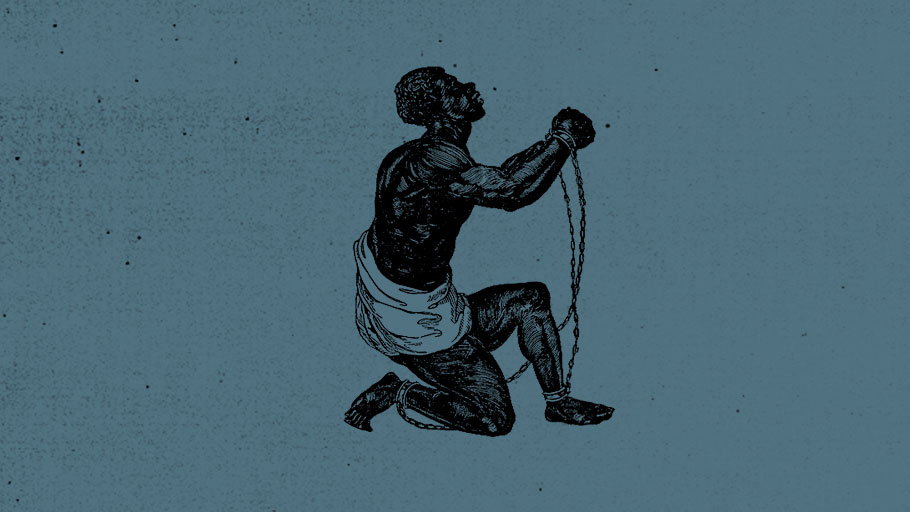

“Between 15-20 million Africans were brought to the America’s alive and against their will.”

Prologue

2017 marks 100 years since the most Honorable Marcus Mosiah Garvey moved the headquarters of UNIA to New York, and 105 years since Marcus Garvey spoke at Howard University about African victims of illegal enslavement and their citizenship:

“I want Negroes first to realize that every Negro is an African citizen. Before we were Americans or West Indians we were Africa citizens. Negroes were never born originally to America or the West Indies. Negroes were originally born to Africa, isn’t it so? Where did your forefathers come from? Georgia? No, they came from Sierra Leone, West Africa or they came from… [word omitted], West Africa. They were first African citizens before they were emancipated by Abraham Lincoln, who made Afro Americans and by Victoria, who made Afro West Indians.

“Now if a Frenchman leaves France — say he has left France 50 years ago and came to America and never asked or applied for naturalization papers. If he lived for 50 years, what would he be? He would be a Frenchman. He would never be an American citizen until he went through the process of action and applied for naturalization. He has first of all, according to the law of the country, to apply for naturalization papers before he can become a naturalized American citizen. If he lived for a hundred years and never applied for naturalization papers he would always be a Frenchman

“Now, sirs, can you remember the time when your forefathers applied for naturalization papers in this country? Your grandfathers never got any naturalization papers. They were gotten from Africa against their will. They were citizens of Africa. Abraham Lincoln set you free, but no law states that emancipation makes you naturalized, and we never went through naturalization, hence we are still and first of all African citizens.”

2017 also represents the 125 anniversary of W.E.B. DuBois’s publishing of his first academic essay called the “The Enforcement of the Slave-Trade Laws” (1892), which led to his classic study Suppression of the African Slave Trade (1898). It is also the 210th year of the 1807 end of the United States involvement in the International Slave Trade. Lastly, 2017 signifies the 10th year of the opening of the African Burial Ground in New York City and the United States Supreme Court’s dismissal of the Reparations law suit filed by Deadria Farmer-Paellman and argued by Roger Warham in Federal Court.

Introduction

According to available records, aboard more than 36,000 ships over a span of almost 500 years, between 15-20 million Africans were brought to the America’s alive and against their will. Although a rather small percentage of those Africans who made it to the Americas alive arrived in what is now called the United States, hundreds of thousands were brought into the country and made to be commerce after federal laws made it illegal to transport sovereign nationals from Africa.

“As late as 1859 there were seven slavers regularly fitted out in New York, and many more in all the larger ports.”

On December 2, 1806, in his yearly message to Congress, widely reprinted in most media outlets at that time, President Thomas Jefferson noted that the “violations of human rights” attending the transnational slave trade and called for its “criminalization” on the first day that was possible (January 1, 1808). Concerning article 1 Section 9 of the U.S. Constitution, Jefferson stated:

“I congratulate you, fellow-citizens, on the approach of the period at which you may interpose your authority constitutionally, to withdraw the citizens of the United States from all further participation in those violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country, have long been eager to proscribe.”

Thomas Jefferson was not the only U.S. President to show concern regarding the U.S. illegal trading and enslaving of humans. His successor, James Madison, also made public commentary on the subject at his second annual message to the U.S. Congress in December of 1810, where he stated the following:

“Among the commercial abuses still committed under the American flag, and leaving in force my former reference to that subject, it appears that American citizens are instrumental in carrying on a traffic in enslaved Africans, equally in violation of the laws of humanity and in defiance of those of their own country. The same just and benevolent motives which produced interdiction in force against this criminal conduct will doubtless be felt by Congress in devising further means of suppressing the evil.”

Despite President Jefferson and Madison’s executive orders regarding U.S. citizens not engaging in the international trade of sovereign Africans, there was a notable amount of illegal trading taking place not long after 1808. In fact, according to historian Carl C. Cutler:

“The act outlawing the slave trade in 1808 furnished another source of demand for fast vessels, and for another half century ships continued to be fitted out and financed in this trade by many a respectable citizen in the majority of American ports. Newspapers of the fifties contain occasional references to the number of ships sailing from the various cities in this traffic. One account stated that as late as 1859 there were seven slavers regularly fitted out in New York, and many more in all the larger ports.”

It is clear from the statements above, particularly that coming from the latter former president, that the federal government acknowledged the fact that human trafficking was taking place and it did very little to stop it. This leads to the question: since so many Africans were brought into the United States illegally and they never gave up their citizenship in the kingdoms in which they were taken from, do their descendants deserve any form of protected rights similar to that of the native Americans?

Section 1: Amicus Curae Brief in the United States Supreme Court Supporting Plaintiff’s Inquiry

In June of 2017, the Africana Research Consultancy Group comprised of Reggie Mabry, Patrick Delices and the author submitted an amicus curiae brief to the United States Supreme Court in support of a pro se litigant named Fenyang Ajamu Stewart. Mr. Stewart was a former doctoral student who had sued the state of North Carolina for various forms of discrimination. But the most interesting part of Mr. Stewart’s Supreme Court petition was the fact that he asked the court to do an inquiry on him due to the fact that hundreds of thousands of African nationals were illegally brought to the United States after the United States has signed international treaties ending the slave trade and its Congress had enacted a ban on human kidnapping in 1808.

The Africana Research group agrees with Mr. Stewart’s position regarding asking the highest court of the land for an inquiry. We believe that such an inquirey would legally situate African Americans in the same way as Native Americans during the first few decades of the 19thcentury. It would also be the first step in explaining the historical fact that close to one million Africans who were illegally brought to the United States after 1808 had come against their own will; that they are the descendants of African Human Trafficking and entitled to broader protections in State and Federal Laws.

Section 2: Human Trafficking and Not Slavery

From 1808 to 1863, 800,000 to 1 million documented and undocumented Africans nationals were illegally trafficked into the United States and were robbed of their inalienable rights and dehumanized by making them into commerce, property, chattel and enslaved. However, the States had a vested interest in hiding this number to cover their conspiracy. It is now clear that this post-1808 system was not slavery according to the laws of the United States. Rather, it was a five decades-long crime of human trafficking, outside the boundaries of law. Various Supreme Court cases hid these realities and covered these crimes by calling the unlawfully captured humans “slaves,” when the truth is that they never gave up their citizenship in the kingdoms and city-states that they were taken from, and this practice was deemed illegal according to international law of that time and the laws of the United States of America.

The Human Trafficking of Africans is a wider study for it deals with not only enslavement but the ripping of Africans by pirates supported by the United States, the forced labor of Africans who were not enslaved, and the conspiracy of the new States that needed this new labor so that the new country could grow. The study of slavery in the United States is a subset of the crime of human trafficking that has modern ramifications.

Section 3: Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

Gibbons v. Ogden was one of the milestone Supreme Court cases that dealt with slavery and the federal government’s ability to regulate commerce. This is the first case where the federal government should have dealt with the well-known fact that citizens of African states were being illegally trafficked and brought into the country after Congress passed the 1807 slave trade act that went into effect in January of 1808. It is also here where the government could have done an inquiry and sent all those who were illegally brought into the country back to their homelands with protection. The Supreme Court mentioned the 1808 Act which banned African nationals from being illegally brought into the United States after 1808 but refused to mention the well-known fact that U.S. nationals, aided and abetted by state and federal agents, continuously brought in African nationals and made them slaves for the purpose of forced labor. The federal government had the authority to have closely watched the states and told them that it would protect the rights of illegally trafficked Africans.

Section 4: Worcester v Georgia (1832)

- Gibbons v. Ogden, the Supreme Court case Worcester v Georgia took place while Andrew Jackson served as the seventh president of the United States. Although this case does not necessarily include the issue of human trafficking as it regards African nationals illegally brought into the United States, it is essential to us because the Justices included in its inquiry the “Age of Discovery” of the New World and laid out the relationship that had developed between the settlers and the native kingdoms. These circumstances are considered the foundation of indigenous sovereignty in the United States. In this case, the Supreme Court admitted that when Europeans came to the Americas they met well organized, indigenous nations. However, the Court never mentioned the fact that the same could be said about African people who were illegally taken from their well-organized nations. The reason the Supreme Court did not do this was because it would have altered and shifted the relationship between the expanding slave plutocracy and those fighting to end slavery. It would have also forced the United States to similarly situate African nationals in the same manner that was done for native people. If the Supreme Court had done an inquiry on the disposition of Africans illegally brought into the United States, the United States would not be the powerhouse that it is today.

Section 5: The United States v. The Amistad (1841)

The Amistad case is probably the most famous case known to the public as it regards captured African nationals and the illegality of human trafficking for the purpose of chattel slavery to the United States. After doing an inquiry into who those Africans nationals (Mende) on the Amistad ship were, the Supreme Court ruled that the United States had no jurisdiction over them because according to the court:

“By those laws, and treaties, and edicts, the African slave trade is utterly abolished; the dealing in that trade is deemed a heinous crime; and the negroes thereby introduced into the dominions of Spain, are declared to be free…They were not slaves, but are kidnapped Africans, who, by the laws of Spain itself, are entitled to their freedom, and were kidnapped and illegally carried to Cuba, and illegally detained and restrained on board of the Amistad; there is no pretence to say, that they are pirates or robbers.”

This analysis given by the Supreme Court speaks directly to the illegal capture and kidnapping of African nationals – in the case, the abduction of sovereign Mede people of West Africa. It is in this moment that the Supreme Court could have expanded this inquiry to make a distinction from the illegal practices taking place in the sovereign territories of Africa and later in the United States by U.S. citizens where the law of the land had “utterly abolished” human trafficking after 1808.

Section 6: Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

The Dred Scott case is another example where the United States erred in not doing an inquiry for people who were illegally trafficked. Although most are familiar with Dred Scott because the Supreme Court Chief Judge Roger Taney, who was the same judge who wrote the opinion for Amistad, shows his contradictions in the Dred Scott case by stating, among many things, that African people were inferior and unfit for social interaction and had no right which a white man had to respect. Some historians believe that Taney’s contradictory opinion in the Scott case as compared to that of Amistad had a lot to do with the fact the he was coerced by the newly elected president, James Buchanan. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court missed a rare opportunity to do an inquiry into the jurisdiction of Africans being trafficked into the United States illegally.

Section 7: The Limitations of John Conyers HR40 Bill & The Proposed Bill by Assemblyman Charles Barron for a New York State Slavery Commission

In the context of legislation penned by the honorable Michigan statesman John Conyers and the esteemed New York Assemblyman Charles Barron, the drafters must be a bit more accurate in seeking federal and state remedies that protect and expand the rights of the descendants of those Africans who were Human Trafficked for the purposes of enslavement by the States and Federal government. Rather than narrowly seeking financial remedies over protected actions, it is best for politicians who earnestly want the best for their constituents to reexamine and properly contextualize the magnitude and limitations of what they are asking for, considering the fact the United States Supreme Court has already rejected the last major push for reparations. They must remember that these legislations currently proposed are representing the group as a whole. Current proposed legislation must focus on the irreparable harm caused to these descendants by failure to seek expanded protections.

Furthermore, not all Black citizens of the United States were harmed by the African Human Trafficking for the purposes of enslavement. However, all were harmed by the forced labor and super exploitation. The United States only afforded the descendants of this Human Trafficking seven years of full protection by the federal government. That protection occurred during the Radical Reconstruction Era. In other words, descendants have rarely been on an equal footing with the American White and Immigrants. Also, the legislating actions are not framed correctly to defeat Federal Judge Posner’s damaging opinion. If not crafted carefully, future efforts for reparations will be found unconstitutional. In addition, both federal and state action are limited by the votes of their peers. And because of the lack of numbers in the legislating bodies, this will always be a hurdle toward seeking remedies. Lastly, potential EXPERTS must be identified to serve as commissioners.

Section 8: Why the Deadria Farmer-Paellman Reparations Lawsuit failed?

The opinions of Judge Richard Posner in the last major reparations case presented before him in 2006 creates several hurdles that cannot be ignored in future Reparations and Legislative activity concerning the rights and remedies of enslaved Africans and their descendants. Judge Posner said this in among other things in 471 F.3d 754 (2006) In re African -American Slave Descendants Litigation Appeals of Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, et al., and Timothy Hurdle, et al.

“In all likelihood, it would still be impossible for them to prove injury, requiring as that would connecting the particular slavery transactions in which the defendants were involved to harm to particular slaves. But in any event, suits complaining about injuries that occurred more than a century and a half ago have been barred for a long time by the applicable state statutes of limitations. It is true that tolling doctrines can extend the time to sue well beyond the period of limitations — but not to a century and more beyond.”

In the context of any new reparations litigation Posner’s statement will destroy plausibility of arguments against defendants without having particular transactions. Any suit would be instantly hit with the dreaded Twombly Iqbal 12(B)6 – Failure to State a Claim defense by a defendant. Furthermore, the Supreme Court has held that in Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly , 550 U.S. 544, 555 (2007):

“[w]hile a complaint attacked by a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss does not need detailed factual allegations, a plaintiff’s obligation to provide the ‘grounds’ of his ‘entitle[ment] to relief’ requires more than labels and conclusions, and a formulaic recitation of the elements of a cause of action will not do.”

Also, the Supreme Court has emphasized that:

“[f]actual allegations must be enough to raise a right to relief above the speculative level,” and that “once a claim has been stated adequately, it may be supported by showing any set of facts consistent with the allegations in the complaint.” Plaintiffs must allege “only enough facts to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.” Id. at 570. But if a plaintiff has “not nudged [ its] claims across the line from conceivable to plausible, the[] complaint must be dismissed.” Id. ; see also Aschroft v. Iqbal , 556 U.S. 662, 679 (2009).

Although previous reparations suits laid the grounds for future suits, they must be properly reevaluated to their fullest so that we can access their successes and limitations as we move forward. In short, the Farmer-Paellman suit went after the wrong defendants. The suit should have attacked the States for their importing Human Trafficked Africans even though the 1807 law was in place forbidding such illegal activity. Agitation, legislation and litigation is meaningless without solid and professional scholarship.

Epilogue: What we must do to move forward: The New Black Agenda

As the 210th anniversary of the 1808 Act Prohibiting Importation of Africans encroaches upon us, we must learn from the mistakes of our past. If we are to engage seriously the reparations cases of old we must ask ourselves some fundamental questions. Those questions must not only be grounded in legalese, but they must also represent the best historical antecedents. For instance, we must ask, what protective rights do we reserve for our ancestors who were illegally trafficked across the Atlantic? And since the law of the land said that this was legal, do we still have citizenship in the nations and kingdoms that we were taken from? How do we identify those nations and kingdoms that we were taken from since many of us have no memory as to what happened? A new Black Agenda must challenge the Federal government for an inquiry, similar to what was done in Worcester V. Georgia (1832). It is only through this that reparations will be available. This new movement must have new faces with new ideas. They must be transparent, incorruptible and “possessed with courage.” The new movement means that we must never give up our African Sovereignty and force the United States to deal with the fact that they were the biggest Human Traffickers in the History of the World. We must retool our efforts with the new information that this summary report gives.

A more detailed peer review study is forthcoming along with a documentary on the subject matter.