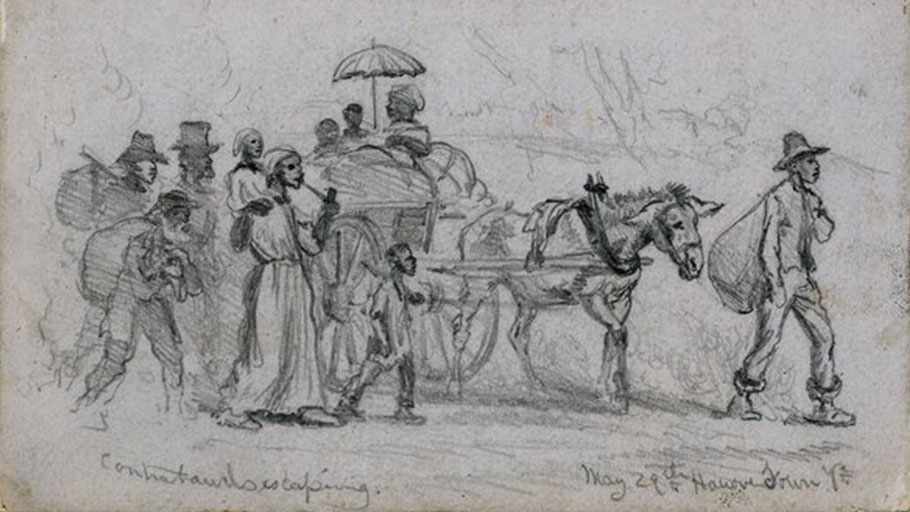

Virginia contrabands in search of freedom. Credit: Edwin Forbes, 1864, Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Library of Congress(LC-DIG-ppmsca-20701)

Editor’s Note: PBS has partnered with Mercy Street’s historical consultants to bring fans the Mercy Street Revealed blog. Anya Jabour, Ph.D., has been teaching and researching the history of women, families and children in the 19th-century South for more than 20 years. She is Regents Professor of History at the University of Montana, where she is affiliated with Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and African-American Studies and has received several awards for teaching and research. In this blog post, Jabour explains how most contraband camps were dismal if not downright dangerous places.

Striking down children and adults, women and men, and blacks and whites, smallpox posed a grave threat in Civil War Virginia. “I wonder why nobody has noticed this outbreak until now?” ponders nurse Mary Phinney. Free black laborer Samuel Diggs provides the answer to this puzzle: “Nobody was looking.”

The opening episode of Mercy Street season two introduces viewers to an early refugee crisis: the plight of runaway slaves in Civil War America. By directing the camera toward the contraband camp adjacent to Mansion House Hospital, the episode directly confronts both the show’s characters and PBS viewers with the hazards facing African Americans during the perilous transition from slavery to freedom.

With no food but what they could carry, no clothes except those they wore, and no home but the one they left behind, escaped slaves were dependent on Union authorities—like Dr. Jedediah Foster at Mansion House Hospital—for both physical protection and basic necessities.

“What are we to do with the women and children?”

Unfortunately for the contrabands, not all Union officials welcomed their role as liberators and defenders of African Americans. Lucy Breckinridge remarked that the Union soldiers who came to her Virginia plantation in 1864 “talked dreadfully about the negroes and said they took no care of them whatever.” Union soldiers’ willingness and ability to offer aid to escaped slaves were indeed limited, lending credence to Confederate Cornelia Peake McDonald’s charge that “the Federals had induced them to fly, but could not succor them in their distress.”

Willing or not, however, Union soldiers were runaway slaves’ best hope for protection and freedom. Declared contrabands of war, escaped slaves formed enclaves everywhere that Union troops gained even temporary control. Near the occupied city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, for instance, planter’s daughter Kate Stone noted that there were “crowds waiting all the time” to take turn to be ferried across the river to a Union camp. By the end of the war, nearly half a million African Americans had fled to refugee camps.

Children made up a significant portion of camp populations. Nearly half of the 2,000 contrabands living in a camp near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were children, for example, while out of fewer than 2,000 African Americans in a camp near Helena, Arkansas, approximately 800 were children. In some cases, children outnumbered adults. At one camp in Missouri, an Iowa soldier reported: “We have now here some two dozen women and not less than a hundred children—more or les [sic] varying in age from two weeks to 15 years.” At a Mississippi plantation, a government agent found 35 “poor wretched helpless negros” living in a cattle shed; the group included a disabled man, five women, and 29 children under the age of 12.

Union authorities were unprepared for the influx of refugees—particularly women and children, who could not be recruited into the ranks of the Union Army. From Fulton, Missouri, one Union captain wrote to his senior officer to ask for advice. “What is proper for me to do in such cases?” he queried, adding with emphasis: “What are we to do with the women and children?”

Conditions in contraband camps varied widely, depending on Union officials’ interest in succoring fugitive slaves as well as the supplies they had available to do so. Some authorities, unsympathetic to runaway slaves’ plight, flatly denied them assistance. For instance, Andrew Johnson, military governor of Tennessee, refused to issue tents to contrabands during the winter of 1863, arguing that to do so would make them overly dependent on government assistance.

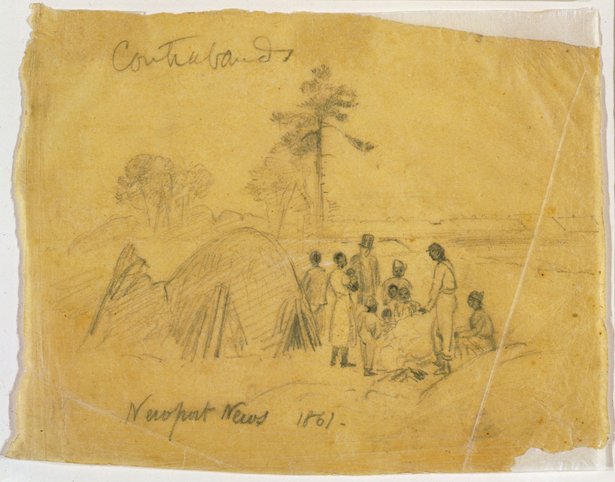

Contraband camp in Newport News, Virginia. Credit: Alfred Waud, 1861, Morgan collection of Civil War drawings, Library of Congress(LC-DIG-ppmsca-21548)

The following year, in neighboring Kentucky, Union guards expelled the families of African American soldiers—400 women and children in all—from Camp Nelson on a frigid night in late November. According to Joseph Miller, a recently enlisted soldier whose wife and four children were among the evacuees, more than 100 refugees ejected from the camp—including his own son—died as a result of exposure.

Even when Union authorities were well-intentioned, with no official policy and no budget for assistance, their ability to assist the refugees was limited prior to the establishment of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands—popularly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau—by the federal government near the end of the war, in March 1865. Thus, private aid agencies—such as the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society—attempted to fill the gap.

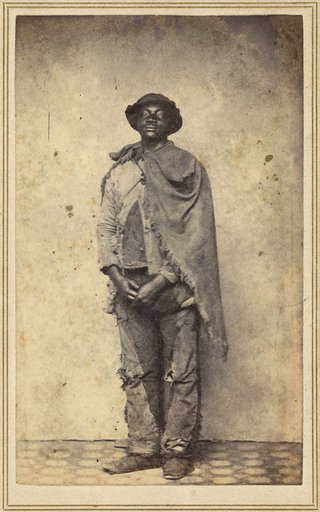

Although dressed in rags, this unknown “Contraband” displays great personal dignity.Gladstone collection, LOC

Just as portrayed on Mercy Street, most contraband camps were dismal if not downright dangerous places. One observer characterized refugee camps as places of “extreme destitution and suffering.” Many camps inhabited by runaway slaves were crowded and filthy, fostering epidemic diseases and resulting in mortality rates of nearly 50 percent. At one camp near Nashville, Tennessee, one quarter of the residents died in a three-month period in 1864. Near Vicksburg, Mississippi, one observer called the contraband camp there “a vast charnel house” with “thousands of people dying without well ones enough to inter the dead.”

Disease, exposure, and hunger took their greatest toll on children. In the shadow of the national capitol, one group of a dozen or so runaways living in a stable in Washington, D.C., included a young girl with tuberculosis, an infant dying of malnutrition, and an orphaned boy with pneumonia. Elsewhere in the capitol city, a group of six children, all under the age of 12 and dressed in rags, took shelter in a shed. And in New Orleans, a newspaper carried the bleak notice: “A negro child has been lying dead at No. 81 Perdido Street … three days. Warm weather is coming on and it ought to be removed.”

Contraband camps like the one portrayed in Mercy Street represented not only a refugee crisis, but also a public health emergency. By demanding that the hospital staff acknowledge the imminent threat posed by a smallpox outbreak among the weary runaways in wartime Alexandria, humanitarian aid worker Charlotte Jenkins also prompts PBS viewers to reflect on our own responsibilities to war refugees in contemporary times.

Sources

- Excerpted and adapted from Anya Jabour, “Topsy-Turvy: How the Civil War Turned the World Upside-Down for Southern Children” (Ivan R. Dee, 2010), quotations pp. 163-168.

Further Reading

- Annual Report of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society

- The Freedmen’s Bureau Online (Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands)

- The Freedmen’s Record (Official publication of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society)

- Jim Downs, “Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction” (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Thavolia Glymph, “’This species of property’: Female Slave Contrabands in the Civil War,” in A Woman’s War: Southern Women, Civil War, and the Confederate Legacy, edited by Edward D. C. Campbell, Jr., and Kym S. Rice (University Press of Virginia, 1996)

- James Marten, “The Children’s Civil War” (University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

- Chandra Manning, “Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War” (Knopf, 2016)

- Willie Lee Rose, “Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment” (orig. pub. 1962; new ed., University of Georgia Press, 1999)

- David Silkenat, “Driven from Home: North Carolina’s Civil War Refugee Crisis” (University of Georgia Press, 2016)

- Amy Murrell Taylor, “How a Cold Snap in Kentucky Led to Freedom for Thousands: An Environmental Story of Emancipation,” in Stephen W. Berry, ed., Weirding the War: Stories from the Civil War’s Ragged Edges (University of Georgia Press, 2011), 191-214.

Illustrations

- Virginia contrabands in search of freedom. Edwin Forbes, 1864, Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ppmsca-20701)

- Contraband camp in Newport News, Virginia. Alfred R. Waud, 1861, Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ppmsca-21548)

- Civil War contraband, Carte de visite photographs from the Gladstone Collection, Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ppmsca-11196)

Anya Jabour, M.A., Ph.D., has been teaching and researching the history of women, families, and children in the nineteenth-century South for more than twenty years. She is Regents Professor of History at the University of Montana, where she is affiliated with Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African-American Studies and has received several awards for teaching and research. She is excited to be sharing her love for the Civil War-era South with PBS.