Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a mass in his hometown of St. Petersburg, Russia, on Jan. 7, 2018. Alexei Nikolsky, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP

By Melani McAlister, The Conversation —

The close relationship between American evangelicals and Russia has lately been discussed widely in the news media. In particular, the Justice Department unsealed a criminal complaint in July against a Russian woman, Maria Butina, for trying to use the National Prayer Breakfast, a star-studded affair, as a “back channel of communication” with prominent American religious and political leaders.

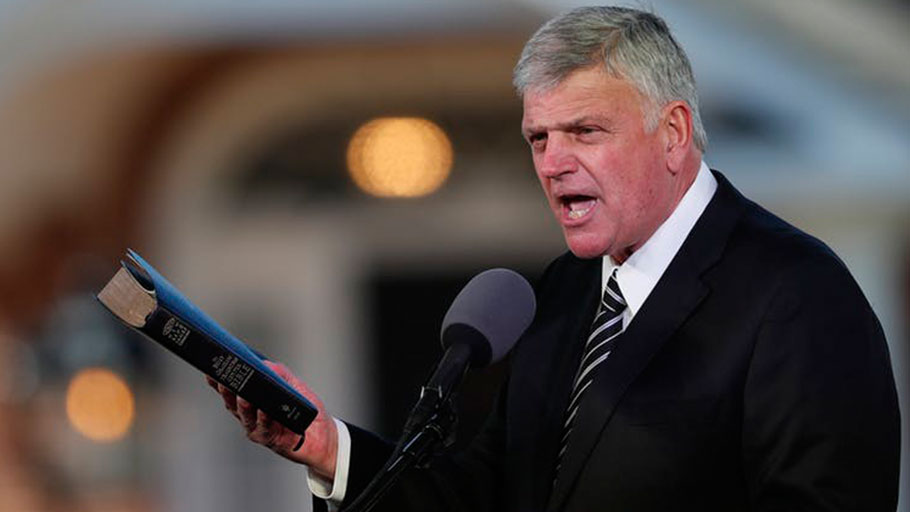

Among them is Franklin Graham, son of the well-known evangelist, Billy Graham, and head of the influential Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

In 2015, Graham famously visited Russia, where he had a warm meeting with President Vladimir Putin. On that trip, Putin reportedly explained that his mother had kept her Christian faith even under communist rule. Graham in turn praised Putin for his support of Orthodox Christianity, contrasting Russia’s “positive changes” with the rise of atheistic secularism in the U.S.

But it was not always so. Once upon a time, American evangelicals saw the Soviet Union and other communist countries as the world’s greatest threat to their faith.

They carried out dramatic and illegal activities, smuggling Bibles and other Christian literature across borders. And yet, today, Russia is their crucial ally.

Bible smuggling

Starting in the 1950s, but intensifying in the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. and European evangelicals presented themselves as intimately linked to the Christians who were suffering at the hands of communist governments.

One evangelical group that emerged at this time was “Open Doors,” whose main aim was to work for “persecuted Christians,” around the world. It was founded by “Brother Andrew” Vanderbijl, a Dutch pastor who smuggled Bibles into the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Brother Andrew and other evangelicals argued that what Christians in communist countries really needed was Bibles – an evangelical view of the centrality of personal Bible reading for the sustenance of the faithful. And Bibles were hard to come by. In 1978, Time magazine reported,

“A Christian’s chances of buying a Bible openly are currently good in Poland, erratic in East Germany, difficult in Czechoslovakia and Hungary…, extremely difficult in Rumania, virtually impossible in the Soviet Union and Bulgaria. Buying a Bible is an out-and-out crime in Albania.”

He turned the smuggling into anti-communist political theater. As he headed toward the border in a specially outfitted vehicle with a hidden compartment that might hold as many as 3,000 Bibles, he prayed. According to one ad that ran in Christian magazines, he said:

“Lord, in my luggage I have forbidden Scriptures that I want to take to your children across the border. When you were on earth, you made blind eyes see. Now I pray, make seeing eyes blind. Do not let the guards see these things you do not want them to see.”

Vanderbijl’s memoir, “God’s Smuggler,” became a bestseller when it was published in 1967.

Taking Jesus to communist world

By the early 1970s, there were more than 30 Protestant organizations engaged in some sort of literature smuggling, and there was an intense, sometimes quite nasty, competition between groups.

Their work depended on their charismatic leaders, who often used sensationalist approaches for fundraising.

For example, in 1966, a Romanian pastor Richard Wurmbrand appearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Internal Security subcommittee, stripped to the waist and turned to display his deeply scarred back.

Rev. Richard Wurmbrand stands stripped to the waist to show scars of torture, as he testifies to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee. AP Photo/Henry Griffin

A Jewish convert and Lutheran minister, Wurmbrand had been imprisoned twice by the Romanian government for his activities as an “underground” minister before he finally escaped to the West in 1964.

Standing shirtless before U.S. senators and the national news media, Wurmbrand testified,

“My body represents Romania, my country, which has been tortured to a point that it can no longer weep. These marks on my body are my credentials.”

The next year, Wurmbrand published his book, “Tortured for Christ,” which became a bestseller in the U.S. He founded his own activist organization, “Jesus to the Communist World,” which also engaged in a good bit of attention-grabbing, intentionally reckless behavior.

In May 1979, for example, two 32-year-old men associated with the group flew their small plane over the Cuban coast, dropping 6,000 copies of a pamphlet written by Wurmbrand. After the “Bible bombing,” they lost their way in a storm and were forced to land in Cuba, where they were arrested and sentenced to 24 years in jail.

They served 17 months before being released in a general pardon of Americans in Cuban jails.

As I describe in my book “The Kingdom of God Has No Borders,” critics hammered these groups for such provocative approaches and hardball fundraising. One leading figure in the Southern Baptist Convention complained that the practice of smuggling Bibles was “creating problems for the whole Christian witness” in communist areas.

Another Christian activist, however, admitted that the activist groups’ mix of faith and politics was hard to beat and had the ability to draw “big bucks.” Indeed, as Time estimated, Bible smuggling groups raised US$30 million a year in the late 1970s – a bit over $100 million today.

After communism: Islam and homosexuality

These days, there is little in the way of swashbuckling adventure to be had in confronting communists. But that does not mean an end to the evangelical focus on persecuted Christians.

After 1989, advocates increasingly focused on Islam as the greatest supposed threat to Christians. That is one of the reasons, I believe, that Putin’s war against Chechen militants in the 1990s, and then his more recent intervention on behalf of Assad’s government in Syria, made him popular with Christian conservatives: They believed Putin was protecting Christians while waging war against Islamic terrorism.

Franklin Graham. AP Photo/John Bazemore

Even Putin’s current policies of cracking down on evangelism do not seem to bother some of his conservative evangelical allies overly. When Putin signed a Russian law in June 2016 that outlawed any sharing of one’s faith in homes, online or anywhere else but recognized church buildings, some evangelicals were outraged, but others looked away.

This is in part because of his claim to be “defender of Christians,” but also because he is seen to be a partner in upholding conservative values on opposing LGBTQ+ rights and nontraditional views of the family. Franklin Graham was among those who waxed enthusiastically about Russia’s laws against “gay propaganda.” Other lesser known activists have been cultivating ties with Russian politicians as well as the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the 21st century, then, evangelical conservatives aren’t promoting their agenda by touting the number of Bibles transported across state lines, but rather on another kind of border crossing: the power of Putin’s reputation as a leader in the resurgent global Right.