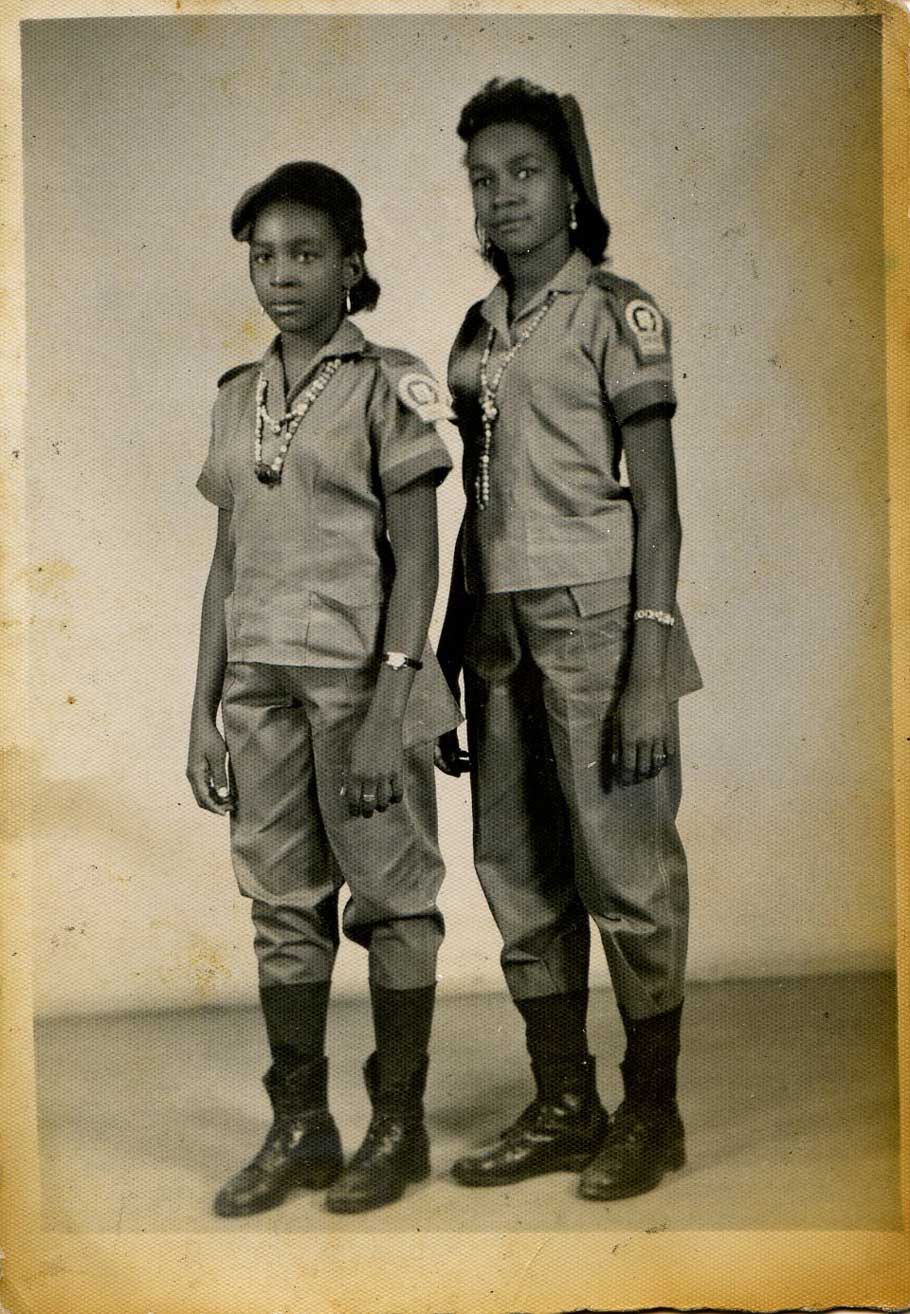

Participants in the Cuban Literacy Campaign march in December 1961. Credit: Liborio Noval.

One of the key strengths of the Cuban campaign was to reframe illiteracy as a collective issue.

By Catherine Murphy, Truthout —

The corporate media have long been looking for ways to discredit Bernie Sanders, and they settled on a surprising statement he made in the 1980s during his tenure as mayor of Burlington when he said, “We have a lot to learn from Cuba.”

Now, they have latched onto a statement he made about Cuba during an interview on “60 Minutes” after winning the Nevada caucuses: “We’re very opposed to the authoritarian nature of Cuba but you know, it’s unfair to simply say everything is bad,” Sanders said. “When Fidel Castro came into office, you know what he did? He had a massive literacy program. Is that a bad thing?”

Ironically, several years earlier, in 2016, President Obama said something quite similar, expressly celebrating Cuba’s hard-won national education system. He said:

Every child in Cuba gets a basic education. That’s a huge improvement from where it was. Medical care, the life expectancy of Cubans, is equivalent to the United States, despite it being a very poor country, because they have access to health care. That’s a huge achievement.

This followed Obama’s historic announcement, in December 2014, that the U.S. would change course from decades of hostile foreign policy toward Cuba, saying that the U.S. embargo on Cuba had not achieved its goals. Obama said that the U.S. would take steps to re-establish diplomatic relations with Cuba and embark on a path of learning to live as neighboring nations, respecting our many differences and collaborate in areas of joint interest.

Bilateral projects began to blossom in the areas of medical and social research. Official delegations from U.S. cities such as Washington, D.C., and New Orleans began to visit Cuba to explore mutual connections. Many of them visited the Havana Literacy Museum to learn about how the Cuban Literacy Campaign mobilized 250,000 volunteer teachers who taught more than 700,000 of their fellow Cubans to read and write.

I spent 10 years recording stories of the youngest women teachers from the 1961 Cuban Literacy Campaign, learning about this experience through the eyes of a multiracial group of Cuban women, who were adolescent girls at the time. Their stories are a powerful testament to the real possibility of a nation overcoming illiteracy and to the personal transformations that can happen in the process.

The first huge leap toward building the Cuban national education system began in September 1960, when Fidel Castro announced to the United Nations General Assembly that the country would become free of illiteracy within one year. This was a seemingly impossible task.

Following this statement to the UN, Cuba made an open call for volunteer teachers. Over 250,000 people came forward. It was voluntary to participate, both for the teachers and the students. The volunteer applicants under 18 years of age were required to submit written permission from both of their parents to take part in the campaign.

Obtaining parental consent was often difficult for the girls, as the work violated gender norms of the day. But many of them entered into an intense period of negotiation with their parents, which in itself was a major departure from the confines of the patriarchal family structure of Cuba at a time, when many young women could not leave their homes without the presence of a chaperone.

Over my years of collecting testimonies, I met two Cuban-American women who were sent to the U.S. by their families in 1961, expressly to stop them from participating in the Literacy Campaign. But 50,000 young women were successful in securing their parents’ permission and embarked upon a groundbreaking path for Cuban women as they left home for the first time.

They went for a two-week training period at the beachside town of Varadero, which had previously been an exclusive resort for the wealthy. Along with methods for teaching literacy, they learned how to give basic health instructions such as how long to boil drinking water and how to make latrines. They were given hammocks, kerosene lanterns and two books that would guide their teaching experience: la cartilla and el manual, lesson plan and teacher guide.

The first section of the teacher guide, under “General Orientation” says:

Establish friendly relationships with your students of cordial respect, because they need your help. Show concern for their problems. Understand them and encourage them so they don’t lose hope. Remember that many of your students may have limitations with their vision or hearing that makes it more challenging to learn. Don’t give orders.

The literacy campaign was the top-priority issue of the nation in 1961. Every institution played a role. The pilot program of volunteer teachers had been in the mountains for a year, and these teachers served as counselors and guides for the multitudes of young teachers who began to arrive in remote mountain regions.

They lived with rural families, working with them during the daytime and teaching classes on nights and weekends. They taught their students how to write the alphabet and sign their names, helping them leave behind humiliating experiences of signing land titles and other essential documents with an X. In the testimonies I recorded, the literacy workers told me stories of teaching mountain people who didn’t know they lived on an island, or who didn’t know the Earth was round.

By the end of 1961, Cuba had reduced illiteracy from 20 percent to under 4 percent, making it one of the most successful literacy campaigns in the world to date.

There were complexities and challenges. Rural life was hard for the students. They had to adapt to living without electricity and running water, wash their clothes in the river, and use the woods or an outdoor latrine instead of an urban bathroom. They received very small stipends, which they often talked about turning over to their host families, but it was often not enough to make up for the chronic undernourishment that those rural families faced. Many of the teachers described eating only rice, only sweet potatoes, or in one case, only mangoes for days upon end.

And there were teaching challenges. Some husbands did not want their wives to take the classes, especially from male teachers. They also had to navigate — and attempt to bridge — the vast social divides of race, class, gender and urban-rural cultural differences and mistrust.

But the testimonies that I collected over a decade reveal how profoundly the young teachers were transformed in the process, and reveal a story of what great feats are possible when people come together to solve pressing social problems. Many of the women said their experience in the literacy program was the first time they felt “autonomous, capable and free.”

Norma Guillard, an Afro-Cuban intersectional feminist and one of the women who inspired me to start gathering testimonies, says she has continued to be a literacy teacher throughout subsequent decades because she has spent her life talking about issues of race and gender justice and LGBT equality. She is now a leading social psychologist on the island and a tireless activist in Black Consciousness and feminist networks around Cuba and the region.

By the end of 1961, Cuba had reduced illiteracy from 20 percent to under 4 percent, making it one of the most successful literacy campaigns in the world to date, and declared the country fully literate under UN definitions.

Five female literacy volunteers return to Havana at the end of the literacy campaign in December 1961. Photographer unknown. Public Domain.

Cubans celebrated the end of the campaign on December 22, 1961, with a huge march through Havana where thousands of volunteer teachers carried lanterns and paper mâché pencils.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) ratified Cuba’s claims of having eradicated illiteracy through a major study that was published in 1965 under the title, “Report on the Method and Means Utilized in Cuba to Eliminate Illiteracy,” authored by Anna Lorenzetto and Karel Neys.

It didn’t end there. Cuba went on to conduct a decades-long adult education program in which the newly literate adults could continue learning through sustained campaigns to achieve third-grade reading levels, then sixth-grade reading levels, and then ninth-grade levels, which is now the standard minimum across the nation.

Many of the young teachers fell in love with the experience of teaching in 1961. Thousands of them went on to dedicate their lives to education across various specialties.

A 20 percent low literacy rate in the U.S. indicates a systemic problem that requires collective strategies toward solutions.

One of the original teachers, Leonela Relys, who was 13 years old in 1961, went on to specialize in adult literacy. Her life’s work became focused on developing a methodology called “Yo Si Puedo” which has now been used in over 30 countries around the world in multiple languages, winning the King Sejong Literacy Prize from UNESCO in 2006 for advancing “individual and social potential through innovative teaching methods” around the globe. The methodology involves the training of facilitators who guide students through a series of audio-visual classes that are specifically developed together with each community to be culturally relevant, appropriate and meaningful for each context.

Through Relys’s work, Cuba’s literacy project thus not only transformed Cuba, it has also benefited Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela, Spain, Angola, South Africa, Jamaica, Maori communities in New Zealand and First Nations communities in Canada. “Yo Si Puedo” methodology has been used with Indigenous languages including Quechua and Aymara in Bolivia, and in Haiti through an innovative radio program in Haitian Creole.

This week, politicians such as Sen. Marco Rubio and corporate media pundits like Anderson Cooper have expressed shock at Bernie Sanders’s decades-old statement that Cuba’s literacy project is something to emulate, but Sanders was absolutely right to say that the U.S. can learn from Cuba on the question of literacy and education.

A CIA Factsheet claims that the U.S. is 99 percent literate, but major national studies show a different picture. In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, sponsored by the National Center for Education Statistics, found that shows one in five U.S. adults (21 percent) do not have sufficient English literacy skills to complete tasks that require comparing and contrasting information, paraphrasing or making low-level inferences. This translates into 43 million U.S. adults who possess low literacy skills. The researchers explained that people categorized by the study as “functionally illiterate” lacked the basic reading and writing skills necessary to manage ordinary, everyday tasks, such as filling out a job application.

From 2011-2014, the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, carried out a large-scale international assessment that set out to measure literacy, numeracy and digital problem-solving. Their results placed study participants in the lowest two categories.

Those 43 million U.S. adults with unmet literacy needs have difficulty navigating complex documents that have critical importance in their lives, such as forms related to health care and health information, getting mortgages and bank loans, and of course, voting ballots.

The mainstream U.S. narrative frames illiteracy as an individualized problem, placing blame on individuals who suffer low literacy. And they often blame themselves. But a 20 percent low literacy rate in the U.S. indicates a systemic problem that requires collective strategies toward solutions.

One of the key strengths of the Cuban campaign was to reframe illiteracy as a collective issue and to encourage all people to participate, bringing together those who had the opportunity to be educated with those who had not, to overcome a national problem. The results and the stories speak volumes.

Bernie Sanders was right when he said the United States has important things to learn from Cuba about literacy.

This article was originally published by Truthout.

Catherine Murphy is founder and director of The Literacy Project. Her documentary Maestra explores the 1961 Cuban Literacy Campaign through the eyes of the youngest women teachers. Her oral history archive of testimonies on the Literacy Campaign is housed at the University of North Carolina Wilson Library.