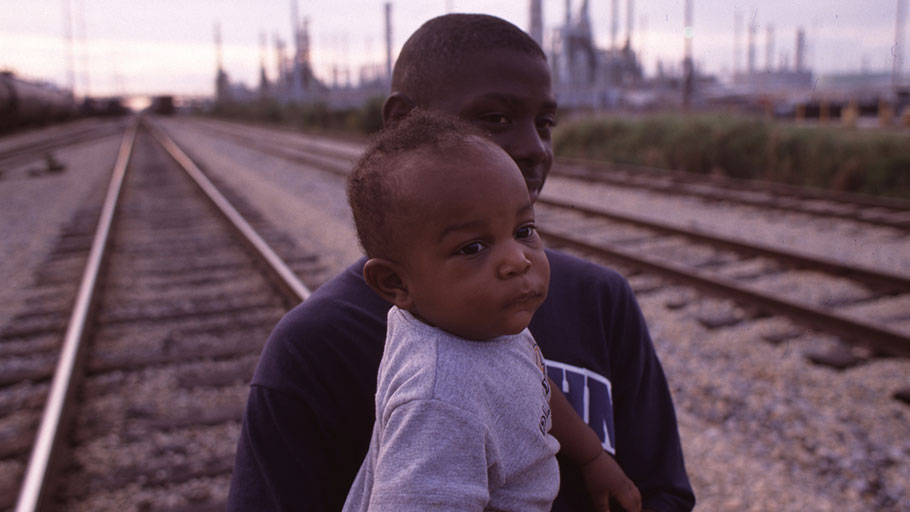

For decades, people living near ‘cancer alley’ have breathed in some of the country’s most toxic air. covid-19 has only worsened the existing public health crisis. Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images.

As predominately Black communities in the polluted areas along the Mississippi from New Orleans to Baton Rouge face heightened risks from COVID-19, the EPA has suspended enforcement of the environmental rules designed to protect them.

For Mary Hampton, social distancing is the easy part. Her biggest vulnerability during the coronavirus pandemic is beyond her control: the massive petrochemical plant just outside her home in Reserve, Louisiana that continues to fill the air with an assortment of toxic chemicals.

“Besides suffering with the virus, we gotta be concerned about more industry because we’re right next to the plant right here,” said Hampton, who at 80 years old, has spent years fighting the Denka plant and other petrochemical facilities in the area as president of the community group Concerned Citizens of St. John. “It’s as if the government doesn’t even care how many people are dying.”

In 2015, the EPA found that the area near the Denka plant had the highest risk of air pollution-caused cancer in the country, nearly 50 times the national average. The other plants lining the 85-mile industrial stretch from New Orleans to Baton Rouge known as “Cancer Alley” have been linked to numerous health problems in the communities pressed up against their fences. As companies continue to develop new facilities with the support of pro-business politicians, Hampton’s long list of family members, neighbors, and friends who’ve died from cancer grows.

And now, her list of friends and family getting sick with the coronavirus is growing, too: her sister’s daughter-in-law, her son-in-law, her nephew’s ex-wife. Her cousin died from the virus in late March, a friend’s husband died last week, a husband and wife in her neighborhood died a few days ago.

Across the country, the coronavirus pandemic poses a severe threat to people whose lungs, immune systems, and hearts have been weakened by environmental contaminants. The risk factor list for severe coronavirus cases issued by the CDC is a litany of conditions aggravated or caused by pollution: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

A dense concentration of oil refineries, petrochemical plants, and other chemical industries stand alongside residential homes in cancer alley. Photo by Giles Clarke/Getty Images.

All of these conditions are also disproportionately common in communities like Hampton’s— predominantly Black or Latino and low-income—that have long been pushed towards housing abutting industrial plants, highways, and train tracks. With 24 deaths so far, including seven deaths connected to a nursing home for veterans, St. John the Baptist Parish has the highest death rate per capita of any county in the United States. St. James Parish, just upriver from St. John, has the fourth highest rate in the country, with six deaths so far. A COVID-19 vulnerability map launched by healthcare data firm Jvion shows that socioeconomic and environmental factors make some Cancer Alley communities particularly vulnerable.

“Disadvantaged communities of color we know have greater exposure to air pollution on average than wealthier white communities,” said John Balmes, a professor of medicine and environmental health in the University of California system and a national spokesperson for the American Lung Association. He notes that scientists who researched the SARS outbreak in China in 2003 found that infected people were more than twice as likely to die from the disease if they were from highly polluted areas. “The interaction that is likely between air pollution and COVID-19 is worrisome, and I haven’t seen any attention to this from a governmental agency,” said Balmes.

“We’re just here dying and waiting to die.”

Quite the contrary: in late March the Environmental Protection Agency issued a near total suspension of its enforcement of environmental laws. The move came amid pressure from the oil industry, which claimed that potential staffing shortfalls during the pandemic would impede its ability to meet regulatory requirements. That means that petrochemical companies like Denka have free reign to keep polluting, making residents ever more vulnerable to the virus.

The coronavirus “is not just a public health issue. It’s directly related to social equity and environmental justice challenges,” said Gina McCarthy, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s directly related to our fight for clean air and clean water and healthy environments.”

“This is what we’re living with every day, every day. And now the EPA is telling the plants that they can emit whatever they want right now, in a time of crisis?” said Hampton. “We’re just here dying and waiting to die.”

Given the lack of availability of COVID-19 testing, researchers say it’s impossible to know yet just how much higher risk polluted communities face in contracting and dying from the virus. But some are beginning to map the prevalence of CDC risk factors, and the results are telling. Researchers at UTHealth in March published a study using census data and the 2018 Health of Houston Survey to identify neighborhoods in the city where residents are most at risk of hospitalization from the virus— neighborhoods with high percentages of people over 60 and with chronic illnesses. All of the highest risk neighborhoods are located on the east side of the city, which is home to a disproportionate number of petrochemical refineries and industrial transportation hubs.

“When you overlay the coronavirus concerns, all it does is just really accentuate the challenges that the community has,” said Adrian Garcia, Commissioner of Precinct 2, which is home to all of the neighborhoods identified in the UTHealth study. He notes that in addition to holding among the largest number of cancer clusters and highest rates of asthma, his district also has one of the highest uninsured rates in the city. After Hurricane Harvey destroyed the area’s only public hospital in August 2017, access to medical services in the area is limited. “You couple together the environmental challenges that the community has long lived under with the social economics that tend to be around the area. Affluent families may not want to live next to a refinery,” Garcia said.

While pollution levels across the globe have temporarily dropped as the roads have largely cleared of commuters, communities like Garcia’s that live near industrial facilities— now more empowered than ever by the EPA’s suspension of rule enforcement—will continue to bear these risks.

Garcia said in an interview last week that there’s been no acknowledgement from other government agencies of the additional risks faced by his community. He’s using money from his own budget and partnering with a private company to try to expand medical services and testing in the area.

African Americans account for 70 percent of all of the deaths in Louisiana so far. They make up just 32 percent of the population.

Some government agencies are beginning to acknowledge the disproportionate effect of the coronavirus on African American communities. In a press conference on Monday, Governor John Bel Edwards revealed data showing that African Americans account for 70 percent of all of the deaths in Louisiana so far. They make up just 32 percent of the population. “That deserves more attention,” he said. “And we’ll have to dig into that and see what we can do to slow that trend down.” He noted that the most common pre-existing condition for people who have died in the state is hypertension, which studies have shown to be connected to air pollution, among other risk factors.

But regional authorities overseeing the heart of the petrochemical industry in Louisiana have failed to acknowledge the role of environmental risk. In response to an inquiry from VICE , the Louisiana state health department said: “COVID-19 is a threat to every person in our state. There are confirmed cases in 62 out of 64 parishes. Each person should take mitigation efforts seriously and follow guidance to minimize the spread of this illness.”

“They’re not wanting to even acknowledge how compromised we already are and what we’re having to deal with here,” said Robert Taylor, director of Concerned Citizens of St. John in an interview last week. “There’s no special testing, no special precaution being taken by anyone—not in the health department, not at the state level.”

On Monday, as positive cases in the parish continued to mount, health officials launched a drive-through testing site for residents in nearby Laplace. Last week, the parish instituted a 9 p.m. curfew.

Concerned Citizens of St. John is committed to fighting for recognition of their heightened risk, even as social distancing poses new challenges for the time being. “We’re fighting for our generation to come. Our lives are almost over, so we’re fighting for our children,” said Hampton. “All you can do is stay in place.”

This article was originally published by VICE.

Sophie Kasakove is a freelance reporter covering the housing and climate crises. She is based in New Orleans. Follow her on Twitter.