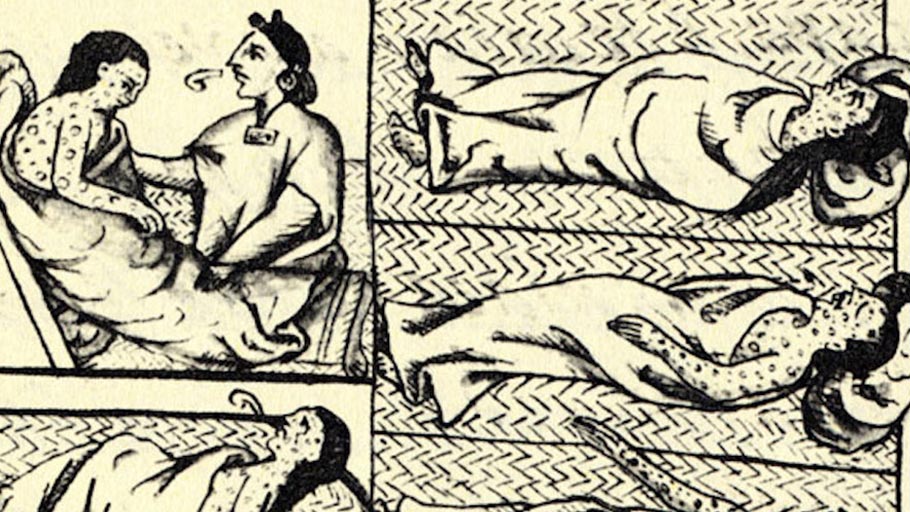

Panel from the Florentine Cortex depicting smallpox outbreaks in the Americas during the 16th century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

But When Cortés’s Soldiers Arrived Carrying a Novel Virus, the Empire First Succumbed to Smallpox and Then Fell to Spain.

By David Bowles, Zocalo Public Square —

Every civilization eventually faces a crisis that forces it to adapt or be destroyed. Few adapt.

On July 10, 1520, Aztec forces vanquished the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men, driving them from Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec empire. The Spanish soldiers were wounded and killed as they fled, trying in vain to drag stolen gold and jewels with them.

The Spanish more than deserved the routing they got, and the conflict should have ended then. But a fateful surprise made those losses insignificant. By September, an unexpected ally of the would-be conquerors had reached the city: the variola virus, which causes smallpox.

How the Aztecs responded to this threat would prove critical.

The Aztecs were no strangers to plagues. Among the speeches recorded in their rhetoric and moral philosophy, we find a warning to new kings concerning their divinely ordained role in the event of contagion:

Sickness will arrive during your time. How will it be when the city becomes, is made, a place of desolation? Just how will it be when everything lies in darkness, despair? You will also go rushing to your death right then and there. In an instant, you will be over.

Facing a plague, it was vital that the king respond with grace. They warned:

Do not be a fool. Do not rush your words, do not interrupt or confuse people. Instead find, grasp, arrive at the truth. Make no one weep. Cause no sadness. Injure no one. Do not show rage or frighten folks. Do not create a scandal or speak with vanity. Do not ridicule. For vain words and mockery are no longer your office. Never, of your own will, make yourself less, diminished. Bring no scorn upon the nation, its leadership, the government.

Retract your teeth and claws. Gladden your people. Unite them, humor them, please them. Make your nation happy. Help each find their proper place. That way you’ll be esteemed, renowned. And when our Lord extinguishes you, the old ones will weep and sigh.

If a king did not follow this advice, if his rule caused more suffering than it abated, then the people prayed to Tezcatlipoca for any number of consequences, including his death:

May he be made an example of. Let him receive some reprimand, whatever you choose. Perhaps punishment. Disease. Perhaps you’ll let your honor and glory fall to another of your friends, those who weep in sorrow now. For they do exist. They live. You have no want of friends. They are sighing before you, humble. Choose one of them.

Perhaps he [the bad ruler] will experience what the common folk do: suffering, anguish, lack of food and clothing. And perhaps you will give him the greatest punishments: paralysis, blindness, rotting infection.

Or will he instead soon depart this world? Will you bring about his death? Will he get to know our future home, the place with no exits, no smoke holes? Maybe he will meet the Lord of Death, Mictlanteuctli, mother and father of us all.

Clearly, the Aztecs took the responsibilities of leadership very seriously. Beyond uplifting morale, a king’s principal duty in times of contagion was deploying his subjects to “their proper place” so that the kingdom could continue to function. This included mobilizing the titicih, doctor-healers with vast herbal knowledge, most of them women pledged to the primal mother goddess Teteoh Innan.

Facing a plague, it was vital that the king respond with grace: “Do not be a fool. Do not rush your words, do not interrupt or confuse people. … Make no one weep.”

What about the rest of the people? As with our own modern call for “thoughts and prayers,” the Aztecs believed their principal collective tool for fending off epidemics was a humble appeal to Tezcatlipoca. The very first speech of their text of rhetoric and moral philosophy was a supplication to destroy plague. After admitting how much they might deserve this scourge and recognizing the divine right of Tezcatlipoca to punish them however he sees fit, the desperate Aztecs tried to get their powerful god to consider the worst-case outcome of his vengeance:

O Master, how in truth can your heart desire this? How can you wish it? Have you abandoned your subjects? Is this all? Is this how it is now? Will the common folk just go away, be destroyed? Will the governed perish? Will emptiness and darkness prevail? Will your cities become choked with trees and vines, filled with fallen stones? Will the pyramids in your sacred places crumble to the ground?

Will your anger never be reversed? Will you look no more upon the common folk? For—ah!—this plague is destroying them! Darkness has fallen! Let this be enough. Stop amusing yourself, O Master, O Lord. Let the earth be at rest! I fall before you. I throw myself before you, casting myself into the place from which no one rises, the place of terror and fear, crying out: O Master, perform your office … do your job!

How many times was this prayer repeated as smallpox ate its cruel way into Mexico, as the domain of the Mexica—ruling people of the Aztec empire—was then already called? We know prayer and the skills and knowledge of the healers were no match for the novel virus.

Smallpox arrived in Mesoamerica with a second wave of Spaniards who joined forces with Cortés. According to one account, they had with them an enslaved African man known as Francisco Eguía, who was suffering from smallpox. He, like many others on the continent of his birth, had no immunity to the disease carried there by the slave traders.

Eguía died in the care of Totonac people near Veracruz, the port city established by the Spanish some 250 miles east of the Aztec capital. His caretakers became infected. Smallpox spreads easily: not only blood and saliva, but also skin-to-skin contact (handshakes, hugs) and airborne respiratory droplets. It raced through a population with no herd immunity at all: along the coast, over the mountains, across the waters of Lake Texcoco, into the very heart of the populous empire.

The epidemic lasted 70 days in the city of Tenochtitlan. It killed 40 percent of the inhabitants, including the emperor, Cuitlahuac. Had he found it increasingly difficult to keep his people’s spirits up as tradition commanded? Had his leadership faltered? Did his subjects pray for his death?

Whatever the case, the memory of that devastation would echo for centuries. Some Nahuas—mostly the sons and grandsons of Aztec nobility—described the devastation decades after the conquest.

Their account harrows the soul:

It started during Tepeilhuitl [the 13th month of the solar calendar], when a vast human devastation spread over everyone. Some were covered in pustules, which spread everywhere, on people’s faces, heads, chests, etc. There was great loss of life; many people died of it.

They could not walk anymore. They just lay in bed in their homes. They could not move anymore, could not shift themselves, could not sit up or stretch out on their sides. They could not lay flat on their backs or even face down. If they even stirred, they screamed out in pain.

Many died of hunger, too. They starved because no one was left to care for the others; no one could attend to anyone else. On some people, the pustules were few and far between. They caused little discomfort, and those folks did not die. Still others had their faces marred.

By Panquetzaliztli [the 15th month of the solar year], it began to fade. At that time the brave warriors of the Mexica managed to recover.

But a hard lesson had been learned. None of the old remedies had worked. Entire families were gone. Funeral pyres effaced the sun. Although Tezcatlipoca may have heeded their supplications at the end, the price he had made his people pay was staggering.

The epidemic was only the beginning of the unexpected forces working in tandem to bring down the Aztec empire. On May 22, 1521—just as Tenochtitlan was beginning to recover, trying to rebuild trade routes, restock its supplies, replant its fields and aquatic chinampa gardens—Cortés returned.

This time he commanded more Spanish troops, men from the same second wave that had brought the smallpox. With them marched tens of thousands of Tlaxcaltecah warriors, the sworn enemies of the Aztecs. Smallpox had reached Tlaxcallan first, but its people—not as densely packed in urban areas like the Mexica—had fared better and were now ready to finish off their rivals.

The massive military force laid siege to the Aztec capital. Even with more than half the population dead or disabled, with little food or water or supplies, the Mexica held the city for three months.

Then, on August 13, 1521, it fell. Emptiness and darkness indeed prevailed.

Lines from a song composed by an unknown Mexica not long afterward sums up the emotions of the survivors:

It is our God who brings down

His wrath, His awesome might

upon our heads.So friends, weep at the realization—

we abandon the Mexica Way.

Now the water is bitter,

the food is bitter: that

is what the Giver of Life

has wrought.

Without the smallpox, it’s much less likely Cortés and his allies could have taken Tenochtitlan. The epidemic exposed the city’s weakness: the need to import essential goods along causeways that could be destroyed to cut the isle off from the world, the vulnerable aqueduct that carried the city’s only fresh water from distant Chapultepec Hill, the tightly packed boroughs in which commoners lived and worked. The Aztecs were brilliant engineers and soldiers, with capable titicih, but the old ways were not enough. No one thought to isolate the infected, to confine the healthy to their homes to keep them safe. And, absent the practice of inoculation discovered by Chinese physicians a few centuries earlier, there was no safer way of building herd immunity in Tenochtitlan.

Without innovative ways to slow it, smallpox helped invaders bring down an empire. That’s the power of novel viruses, proven time and again. We would do well to learn the lesson.

Source: Zocalo Public Square

David Bowles is an author, translator and associate professor of Literatures and Cultural Studies at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. His most recent book is They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems. He translated the Nahuatl texts in this article.