Protesters chant “Say His Name — George Floyd!” near a memorial for George Floyd in Minneapolis on June 2. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

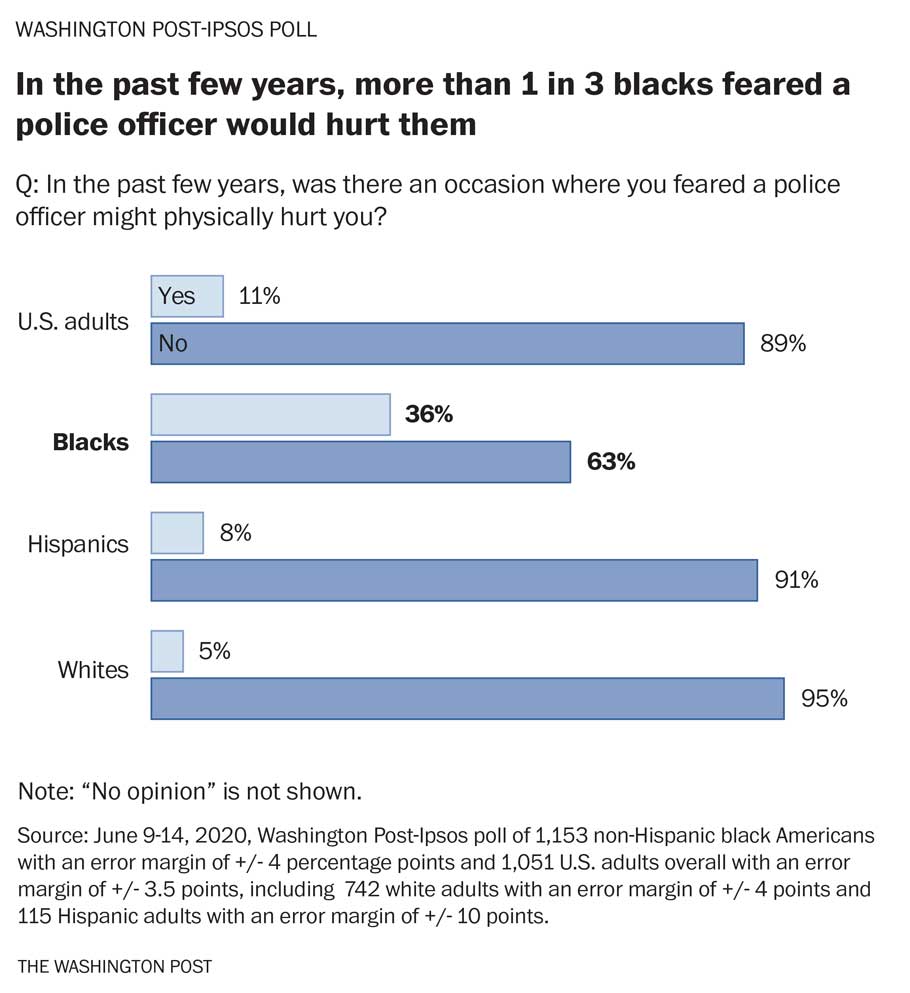

More than a third of black Americans say there was an occasion when they feared being hurt by a police officer.

By Cleve R. Wootson Jr., Scott Clement and Emily Guskin, The Washington Post —

Jackie Beckley believes the video of the final moments of George Floyd’s life may finally help white friends and colleagues understand what she has labored to tell them about her experience as a black woman: the uneasy feeling that rose when her son was late checking in, her hesitation to take a job transfer “down South,” even her anger at disparate treatment by store clerks.

The graphic video of a black man slowly dying on a Minneapolis street had saddened and angered her, but the multicultural jolt of outrage that energized protesters across the United States gave her hope. She wondered whether people who did not share her experiences would finally begin to understand them.

“I think because white America was able to see it, it’s no longer them living in an oblivious world,” said Beckley, a 58-year-old call center employee from the Columbus, Ohio, area, who said many of her white friends and colleagues saw the clip. “In order for our society to get better, they have to look and see the things that are wrong in their world — not just ours.”

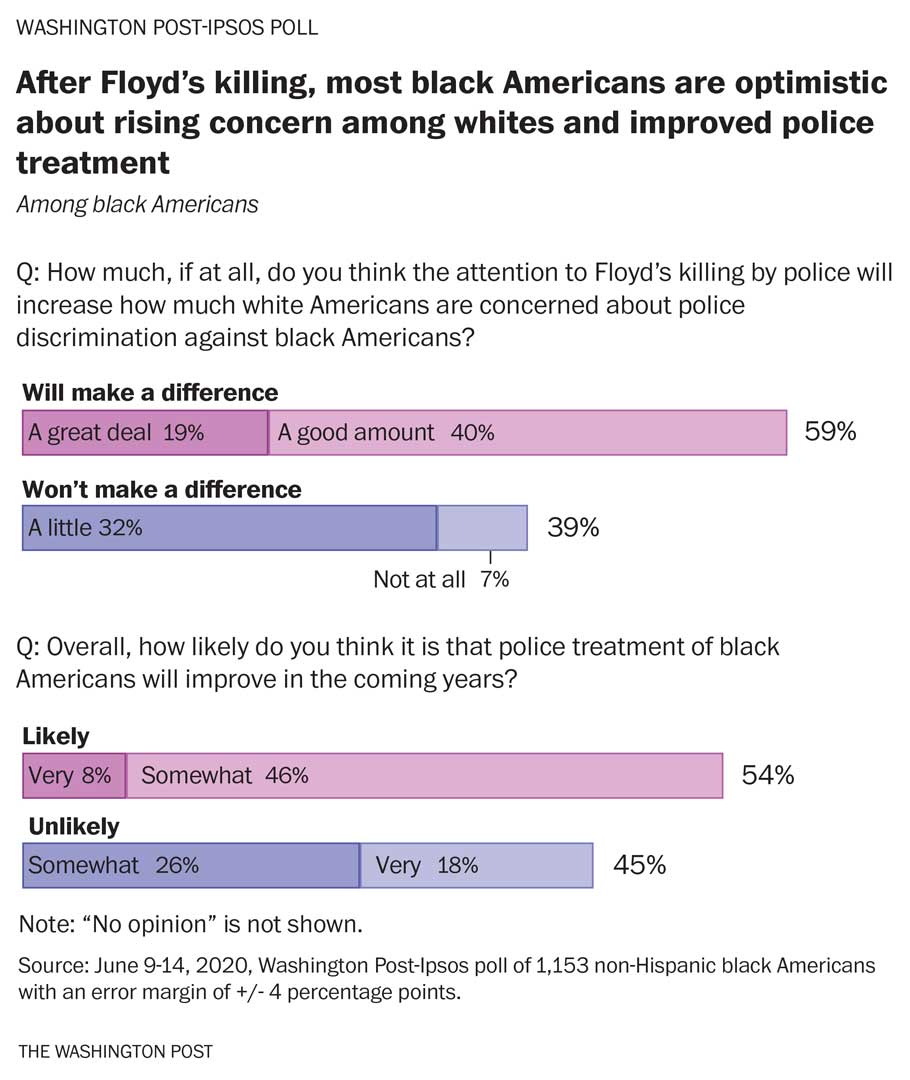

Many black Americans have similar frustrationsand asimilar optimism, according to a Washington Post-Ipsos poll of black Americans that was conducted as large demonstrations still rocked American cities.

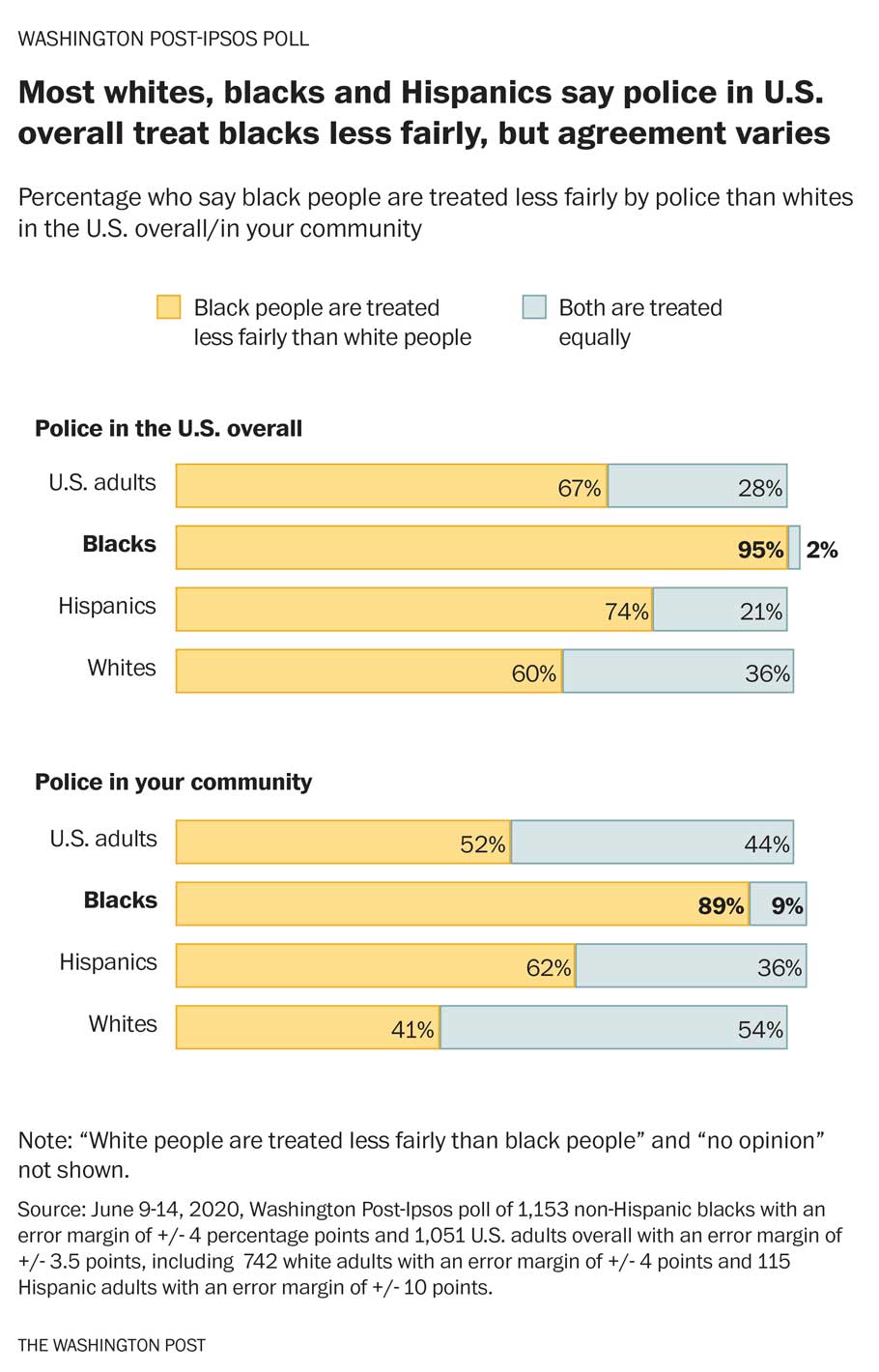

While a majority of Americans across all racial groups report feeling sad, angry and troubled by Floyd’s killing, black people perceive the country’s police forces as far more racially biased than white people do,the poll finds. More than half of black adults say they or someone they know had an unfair interaction with police in the past few years. More than a third say there was an occasion when they feared being hurt by apolice officer— much higher than the shares of white and Hispanic Americans reporting the same experiences.

But black people also largely believe Floyd’s death could be a catalyst for change, in part because people of all colors have participated in protests in hundreds of cities and towns and demanded movement from political leaders, actions several survey respondents cited in follow-up interviews. The survey suggests that the avalanche of revulsion to Floyd’s video-recorded killing — including criticism of the Minneapolis police officers’ actions across the political spectrum and a newfound embrace of the slogan “Black Lives Matter” — has sparked hope among black Americans that the country will address discrimination in ways it did not after past incidents in which police killed black people.

But black people also largely believe Floyd’s death could be a catalyst for change, in part because people of all colors have participated in protests in hundreds of cities and towns and demanded movement from political leaders, actions several survey respondents cited in follow-up interviews. The survey suggests that the avalanche of revulsion to Floyd’s video-recorded killing — including criticism of the Minneapolis police officers’ actions across the political spectrum and a newfound embrace of the slogan “Black Lives Matter” — has sparked hope among black Americans that the country will address discrimination in ways it did not after past incidents in which police killed black people.

Thousands of protesters march through downtown Minneapolis on May 31. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

Nearly 6 in 10 black Americans believe Floyd’s killing will increase white Americans’ concern about racial discrimination by police. And a narrow majority think police treatment of black Americans is likely to improve in coming years.

“It’s white people’s participation, that’s the difference. They’re the ones who have to see it,” said Dexter Banks, a 46-year-old project manager from Memphis. “We can complain all day long, but if we’re not the majority, there’s not much we can do. They have to have an interest in our problems. As long as they are interested in it, then we have a shot.”

The Post-Ipsos poll shows that most white and Hispanic adults share the view of black Americans that they are treated less fairly than white Americans by police in the United States overall. About half of white Americans say police are generally more likely to use deadly force against black people than white adults, while two-thirds of Hispanics and more than 9 in 10 black Americans say the same.

But opinions splinter along racial lines when respondents were asked about the root causes of those disparities.

But opinions splinter along racial lines when respondents were asked about the root causes of those disparities.

Black Americans see a panoply of reasons for mistreatment by police: departments not holding officers accountable for misconduct, police who assume black people are criminals or police who are racist. Three-quarters say white people falsely accusing black people of a crime factors heavily into bad behavior by police, while most also say a lack of community oversight or police training are big contributors.

Among white Americans who say black counterparts are treated less fairly by police, about 8 in 10 say a major reason is lack of accountability for misconduct, while about two-thirds say police assume black Americans are criminals. Smaller majorities blame racist police officers, poor police training and lack of community oversight. Just over 3 in 10 say false accusations by white people are a major reason for unfair treatment.

Madelyn Dancy, 28, outside her home in Memphis. (Brandon Dill for The Washington Post)

Despite optimism about rising white concern with police misconduct, 81 percent of black adults say most white Americans don’t understand the level of discrimination black Americans face in everyday life, hardly changed from a Post-Ipsos poll in January.

“It’s racial and cultural issues that are ingrained in the police department. It’s a reflection of society,” said Madelyn Dancy, a 28-year-old from Memphis who is in school to become a pharmacist. Black people are “taught from a young age not necessarily to fear the police, but you do what you have to do so they don’t have any reason to harm you. Why do we have to do that? Young white males don’t have to do the same conversations as young black males’ families.”

The 55 percent majority of black Americans who say they or a close friend or family member felt unfairly treated by police in the past few years compared with 20 percent of white adults. Younger black Americans are more likely to say they have personally been treated unfairly by police: 38 percent of black adults under age 50 reported unfair treatment in the past few years, compared with 25 percent of those ages 50 to 64, and 17 percent of those 65 and older.

For Charles Johnson, a government contractor from the D.C. area, seeing the clip of Floyd’s killing was a reminder of the times he has been stopped by police. Even though the infractions were minor, Johnson said, officers still pulled him from his car, patted him down and sat him on the curb while they searched his vehicle.

For Charles Johnson, a government contractor from the D.C. area, seeing the clip of Floyd’s killing was a reminder of the times he has been stopped by police. Even though the infractions were minor, Johnson said, officers still pulled him from his car, patted him down and sat him on the curb while they searched his vehicle.

Years later, the memory still stings. “Now, I prepare myself for an unpleasant encounter whenever I see blue lights in my mirror,” he said.

Conversely, Felicia Marquez, 57, a Port Richey, Fla., woman on disability, said she had been treated with kindness and patience by officers called to her home for a heated altercation — civility she attributes to the fact that she is white.

Marquez said the police were summoned after she threatened to kill a roommate who stole her car.

“If I had been black and threatened her life, they may have thrown me on the floor, but I’m white. … I really think they wouldn’t have been that nice to me if I was black. The way I was acting? They would not have put up with me.”

Both black and white Americans appear skeptical of remedies that might come from the White House. President Trump receives negative marks from black and white respondents alike for his response to Floyd’s killing, although black Americans are far more critical.

Nine in 10 black Americans disapprove of Trump’s response to Floyd’s killing, and about three-quarters disapprove of his response to the protests that followed it. Among white Americans, about 6 in 10 disapprove of Trump’s response to Floyd’s killing and the protests alike.

White Americans’ views on racial discrimination continue to divide sharply along partisan lines, with 9 in 10 Democrats saying black people are treated less fairly by police, compared with two-thirds of independents and just under 4 in 10 Republicans. There are also regional and gender divisions among white adults, with rural residents and men — two of Trump’s most loyal supporters — less likely to say police treat black people less fairly.

Somia Stewart, 3, walks through a memorial for Floyd at the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis earlier this month. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

The protests that followed Floyd’s killing were almost universally supported by black Americans, at 91 percent, including 73 percent who support them “strongly.”

Support for the demonstrations is strong across generational, educational and income levels, but most black Americans were critical when it came to destructive acts: 57 percent say vandalism and looting undermined the goals of the protests a great deal or a good amount.

“I think the burning and the looting, destroying the buildings was a bad thing,” said Lamone Jacobs, 49, a janitor from Minneapolis, who said he has had trouble getting to and from work because of the protests and worries that people will vandalize his home. “It diverted it from the message. … I know what the officers did was bad and all that, but [the protesters] didn’t need to do anything like that. Sprinkling fear all over things isn’t going to help.”

Dancy, the Memphis pharmacy student, said she had participated in several peaceful protests. Although she didn’t condone breaking the law, she said she understood the anger of people who turned to more extreme measures, like vandalism and seeking to publicly shame people who say racist things on the Internet.

“Society is finally at the point where we’re not going to tolerate it,” she said. “It’s not nice to ruin people’s lives, but you have people going on social media blaring these horrible things about a group of people. Now, you can’t do that and not think you’re going to get fired. … Somebody is going to make it public.”

Johnson, the Washington-area government contractor, said interactions with officers had already affected his life — and the lives of his children.

Because of the way he had been treated by officers during traffic stops, he instructed his children from a young age about how to behave around police. If their car was ever approached by an officer, he told them, they should be as quiet and nondisruptive as possible.

On one trip through Ohio, Johnson was stopped, and his daughter, then 5 years old, heeded his advice, sitting quietly in her car seat, playing with her Nintendo DS as he spoke with the police officer.

A short time after the officer pulled away, he again found himself unsettled, but not because of the lawman’s actions.

His daughter “got her Nintendo DS out and showed me [a picture of] the front face and the profile picture she had taken of the officer,” Johnson said. “She had obviously gotten the lesson.”

The Post-Ipsos poll was conducted June 9-14 through Ipsos’s KnowledgePanel, a large online survey panel recruited through random sampling of U.S. households. Results among the sample of 1,153 non-Hispanic black adults have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus four percentage points; the error margin is 3.5 points among the parallel sample of 1,051 U.S. adults overall and four points among the sample of 742 white adults.

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.

Cleve R. Wootson Jr. is a national political reporter for The Washington Post, covering the 2020 campaign for president. He previously worked on The Post’s General Assignment team. Before that, he was a reporter for the Charlotte Observer.

Scott Clement is the polling director for The Washington Post, conducting national and local polls about politics, elections and social issues. He began his career with the ABC News Polling Unit and came to The Post in 2011 after conducting surveys with the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project.

Emily Guskin is the polling analyst at The Washington Post, specializing in public opinion about politics, election campaigns and public policy. Before joining The Post in 2016, she was a research manager at APCO Worldwide and prior to that, she was a research analyst at the Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project.

Dan Balz and Vanessa Williams contributed to this report.