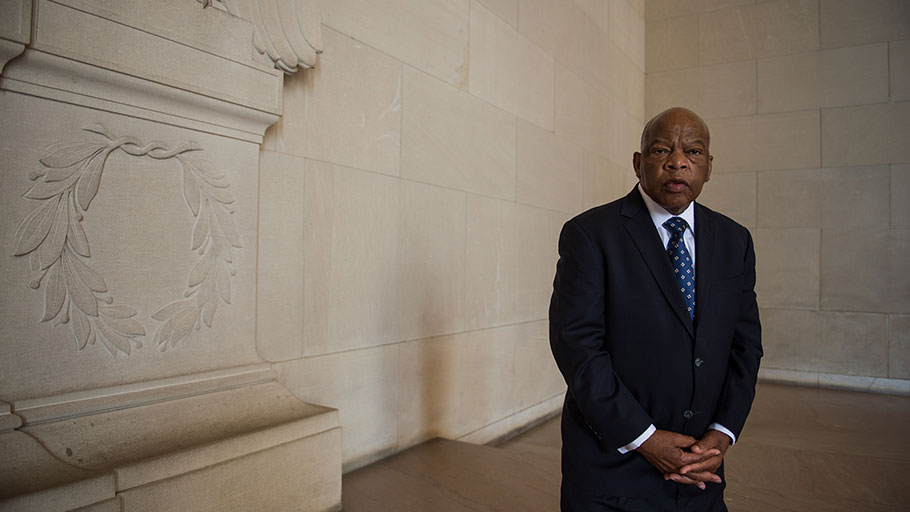

John Lewis at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington in 2013. (Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post)

By Laurence I. Barrett, The Washington Post —

John Lewis, a civil rights leader who preached nonviolence while enduring beatings and jailings during seminal front-line confrontations of the 1960s and later spent more than three decades in Congress defending the crucial gains he had helped achieve for people of color, has died. He was 80.

His death was announced in statements from his family and from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.). Advisers to senior Democratic leaders confirmed that he died July 17, but other details were not immediately available.

Mr. Lewis, a Georgia Democrat, announced his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer on Dec. 29 and said he planned to continue working amid treatment. “I have been in some kind of fight — for freedom, equality, basic human rights — for nearly my entire life,” he said in a statement. “I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.”

His last public appearance came at Black Lives Matter Plaza with D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser (D) on June 7, two days after taping a virtual town hall online with former president Barack Obama.

While Mr. Lewis was not a policy maven as a lawmaker, he served the role of conscience of the Democratic caucus on many matters. His reputation as keeper of the 1960s flame defined his career in Congress.

When President George H.W. Bush vetoed a bill easing requirements to bring employment discrimination suits in 1990, Mr. Lewis rallied support for its revival. It became law as the Civil Rights Act of 1991. It took a dozen years, but in 2003 he won authorization for construction of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall.

In 2012, when Rep. Paul C. Broun (R-Ga.) proposed eliminating funding for one aspect of the Voting Rights Act, Mr. Lewis denounced the move as “shameful.” The amendment died.

In 2016, Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) spoke about preparing for the 1961 Freedom Rides and offered advice for those engaging in peaceful protests decades later. (Ashleigh Joplin, Randolph Smith, Rhonda Colvin/The Washington Post)

Mr. Lewis’s final years in the House were marked by personal conflict with President Trump. Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, Mr. Lewis said, rendered Trump’s victory “illegitimate.” He boycotted Trump’s inauguration. Later, during the House’s formal debate on whether to proceed with the impeachment process, Mr. Lewis had evinced no doubts: “For some, this vote might be hard,” he said on the House floor in December 2019. “But we have a mandate and a mission to be on the right side of history.”

Born to impoverished Alabama sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was a high school student in 1955 when he heard broadcasts by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. that drew him to activism.

“Every minister I’d ever heard talked about ‘over yonder,’ where we’d put on white robes and golden slippers and sit with the angels,” he recalled in his 1998 memoir, “Walking With the Wind.” “But this man was talking about dealing with the problems people were facing in their lives right now, specifically black lives in the South.”

Mr. Lewis vaulted from obscurity in 1963 to head the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which he helped form three years earlier. SNCC, pronounced “snick,” had quickly become a kind of advance guard of the movement, helping organize sit-ins and demonstrations throughout the South.

Within weeks of taking over SNCC, Mr. Lewis was in the Oval Office with five nationally known black leaders, including King, Whitney Young, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer and Roy Wilkins.

Labeled the “Big Six” by the press, they rejected President John F. Kennedy’s request to cancel the March on Washington planned for that August that promised to lure hundreds of thousands of protesters to the doorstep of the White House to push for strong civil rights legislation. The president argued that the march would inflame tensions with powerful Southern politicians and set back the cause of civil rights.

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his aspirational “I Have a Dream” speech. Mr. Lewis, at 23 the youngest speaker, gave a prescient warning: “If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. . . . We must say, ‘Wake up, America, wake up!’ For we cannot stop, and we will not be patient.”

The toughest of the major addresses, Mr. Lewis’s text had in fact been toned down earlier that day at the behest of his seniors — including King, his mentor. They feared that explicit condemnation of the Kennedy administration’s timidity and the threat of a “scorched earth” approach would create a political backlash. (With the death of Mr. Lewis, all of the speakers from the March are now deceased.)

The contrast with his elders symbolized Mr. Lewis’s unusual role in those tumultuous years. At critical moments, he rebuffed their advice to give legislation or litigation more time. Handcuffs and truncheons never dulled his belief in confrontation. Yet he stoutly opposed the militant black nationalists such as Stokely Carmichael who would later take over SNCC.

As the last survivor of the “Big Six,” Mr. Lewis was the one who kept striving for black-white amity. Time magazine included him in a 1975 list of “living saints” headed by Mother Teresa. With only mild hyperbole, the New Republic in 1996 called him “the last integrationist.”

Taylor Branch, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the civil rights movement who had known Mr. Lewis since the mid-60s, said in an interview, “His most distinguishing mark was steadfastness. He showed lifelong fidelity to the idea of one man, one vote — democracy as the defining purpose of the United States.”

“John Lewis saw racism as a stubborn gate in freedom’s way, but if you take seriously the democratic purpose, whites as well as blacks benefit,” Branch added. “And he became a rather lonely guardian of nonviolence.”

On Inauguration Day 2009, Obama, the country’s first black president, gave Mr. Lewis a photo with the inscription: “Because of you, John.” It joined a memorabilia collection that included the pen President Lyndon B. Johnson handed him after signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Ironically, Mr. Lewis had backed the front-runner, Hillary Clinton, in the nominating contest’s early days because of a personal bond with both Clintons. But he switched allegiance once Obama gained some traction.

Bloody Sunday

Passage of the Voting Rights Act, which provided incisors for the 15th Amendment 95 years after its enactment, is the Lewis saga’s richest chapter, what he called “the highlight of my involvement in the movement.”

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was beneficial in terms of public accommodations and employment, but its voting provision was ineffective.

Civil rights workers were attacked frequently, occasionally fatally. Torching and dynamiting of black churches were rising. Perpetrators, though often known, went unpunished. Local registrars continued to bar blacks. Only if black citizens could vote in large numbers, civil rights leaders believed, would Deep South officials enforce laws.

But Johnson told King in December 1964 that Congress, dominated by old-line Southern lawmakers, would reject new legislation.

Both SNCC and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) decided to step up organizing in Selma, Ala. Black residents there constituted half the population, but only 1 percent could vote.

Weeks of demonstrations produced only confrontations with police. During one set-to, an officer shot an unarmed local resident. In the aftermath, an SCLC staffer proposed a large protest march, from Selma to the state capital, Montgomery.

King was in Atlanta, where his senior advisers persuaded him to stay. The SNCC executive committee, increasingly resentful of SCLC’s dominance, voted to avoid the event. But SNCC Chairman Lewis would not allow himself to abstain. That decision, he said later, “would change the course of my life.”

March 7, 1965, became known as Bloody Sunday. With the SCLC’s Hosea Williams, Mr. Lewis led 600 people to the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Selma’s outskirts. There, police and mounted “posse men” — deputized civilians — blocked them.

Ordered to disperse, the procession held its ground. The troopers charged. Network cameras filmed police in gas masks brutalizing unarmed men, women and children, many dressed for church. Millions that night saw police using clubs and tear gas chasing terrified civilians. Mr. Lewis, his skull fractured, went to the hospital along with 77 others.

“I remember how vivid the sounds were as the troopers rushed toward us,” he wrote in his memoir, co-authored with Michael D’Orso. “The clunk of the troopers’ heavy boots, the whoops of rebel yells from the white onlookers, the clip-clop of horses’ hoofs hitting the hard asphalt, the voice of a woman shouting, ‘Get ’em!’ ”

Bloody Sunday pricked the national psyche deeply. When King called for reinforcements for a second march to take place on March 9, which he would lead, hundreds of volunteers, white and black, hurried to Selma. A white minister was beaten and killed by segregationists.

Meanwhile, Johnson had an epiphany. Widespread revulsion was so keen that strong voting rights legislation would be politically feasible after all. The president announced the details to a joint session of Congress on March 15, equating Selma’s significance with that of Lexington, Concord and Appomattox.

When Johnson signed the bill Aug. 6, Mr. Lewis viewed it as “the end of a very long road.” It was also the beginning of the process that extended the franchise to Southern blacks, including Mr. Lewis’s mother, who had opposed her son’s activism.

The bigger revolt

John Robert Lewis was born Feb. 21, 1940, near Troy, Ala., the third of 10 children of Eddie Lewis and the former Willie Mae Carter. Tenant farmers for generations, they saved enough money to buy their own 100 acres in 1944.

John — called Preacher because he sermonized chickens — was the odd child out. He loved books and hated guns. He never hunted small game with other kids. His petition for access to the Pike County library went unanswered.

“White kids went to high school, Negroes to training school,” Mr. Lewis told the New York Times in 1967. “You weren’t supposed to aspire. We couldn’t take books from the public library. And I remember when the county paved rural roads, they went 15 miles out of their way to avoid blacktopping our Negro farm roads.”

College seemed impossible until the family learned of the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville. Aspiring black preachers willing to take campus jobs could attend free.

Mr. Lewis arrived determined to perfect his “whooping” — preaching at a high emotional pitch — but he soon found the pull of social activism irresistible. With other Nashville students, he came under the influence of a Vanderbilt graduate student, James Lawson, who had been imprisoned for refusing military service during the Korean War.

Years later, Mr. Lewis successfully applied for conscientious objector status during the Vietnam conflict and broke with Johnson over the war issue earlier than the other “Big Six” leaders.

In ad hoc workshops, Lawson taught “New Testament pacifism” (how to love rather than strike the enemy tormenting you) and Gandhi-style civil disobedience (staying calm when punched in the head).

These lessons mattered in 1960 as the Nashville Student Movement conducted sit-ins aimed at forcing retailers to allow black customers to use the stores’ eateries. Mr. Lewis experienced his first arrest when police collared the quiet young demonstrators, not the roughnecks who had been knocking them off stools.

As the Nashville campaign broadened to include other targets, Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP’s legal lion, delivered a lecture at Fisk University in Nashville, advising restraint. Don’t go to jail, he suggested. Let the NAACP go to court.

Mr. Lewis was appalled. Marshall’s admonitions, he said, “convinced me more than ever that our revolt was as much against this nation’s traditional black leadership structure as it was against racial segregation and discrimination.” The students ultimately prevailed in Nashville.

King wanted to blend the Nashville activists and counterparts elsewhere into an SCLC youth auxiliary. But Lawson argued the SCLC was too cautious. Discussions on the issue led to SNCC’s creation in 1960. Mr. Lewis was an enthusiastic recruit.

Even before Mr. Lewis graduated in 1961 with his preacher’s certificate, he no longer aspired to the ministry. With other SNCC members from Nashville, he volunteered to join an older group, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), in riding inter-state buses throughout the South. The Supreme Court had already ruled that depots could not be segregated, but that decision was being ignored.

The “Freedom Rides” aroused fierce resistance. Arsonists torched buses in Anniston, Ala., and Birmingham. In several cities, police either looked the other way while crowds beat the riders or arrested the so-called “outside agitators.” Violence became so serious that CORE withdrew.

The SNCC contingent refused to quit. Mr. Lewis, who absorbed his share of bruises and arrests, wound up spending 22 days in Parchman Farm, a Mississippi penitentiary infamous for primitive conditions. But the Freedom Rides drew national attention to the desegregation campaign and attracted recruits. And the Kennedy administration began formal implementation of the Supreme Court decision.

SNCC gained prominence and confidence in its strategy. “We now meant to push,” Mr. Lewis recalled. “We meant to provoke.”

But the group suffered growing pains, including unstable leadership. In June 1963, SNCC’s third chairman resigned suddenly. Mr. Lewis came to Atlanta for an emergency meeting. It ended with his election as chairman.

Chronically broke, SNCC paid its chairman $10 a week plus rent for a dingy apartment. Mr. Lewis would hold the post for three years — longer than anyone else — but tensions scarred his experience. Continued attacks on blacks in the South, growing unrest in northern ghettos and the fact that mainstream leaders declined to break with President Johnson combined to strengthen SNCC’s separatist element.

Carmichael, that faction’s charismatic leader, preached black nationalism and criticized Mr. Lewis as too measured and accommodating, a “little Martin Luther King.” In 1966, Carmichael (who later renamed himself Kwame Ture) was chosen as chairman. SNCC’s white members were shunted aside and urged to leave. Even 30 years later, Mr. Lewis would say of his ouster: “It hurt me more than anything I’ve ever been through.”

Mr. Lewis eventually returned to Atlanta to join the Southern Regional Council, which sponsored community development. In 1968, he joined Robert Kennedy’s campaign for the Democratic nomination for president, as a liaison to minorities. He was with the entourage in Los Angeles when Kennedy was assassinated.

Although the murder devastated him, campaigning had sharpened Mr. Lewis’s interest in seeking public office. So did his marriage, later that year, to Lillian Miles, a librarian by profession and a political junkie by avocation. She was one of his principal advisers until her death in 2012.

Survivors include a son, John-Miles Lewis.

‘Off-the-charts liberal’

Mr. Lewis was serving as executive director of the Southern Regional Council’s Atlanta-based Voter Education Project, which helped register millions of blacks, when he ran unsuccessfully for a U.S. House seat in 1977. The position had been vacated when Rep. Andrew Young was tapped by President Jimmy Carter to become ambassador to the United Nations.

Carter subsequently named Mr. Lewis associate director of ACTION, then the umbrella agency of the Peace Corps, VISTA and smaller antipoverty programs. Mr. Lewis headed the domestic division.

His enthusiasm for the assignment cooled when he concluded that the White House was indifferent to VISTA’s mission. He also refused to take sides when Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) challenged Carter’s renomination in 1980. His neutrality irked both camps.

Mr. Lewis resigned in 1979, returning to Atlanta determined to enter politics. He won a city council seat in 1981, part of that body’s first black majority. His initial gambit — to tighten the council’s ethics code — evoked angry resistance.

He cemented his contrarian image by opposing a major road project, arguing that it would disrupt residential neighborhoods and worsen pollution. The road’s backers, including a group of black clergy, gave the controversy a racial tinge. Opposition to the program, the ministers’ leaflet said, was “a vote against the [black] mayor and the black community.”

It was a familiar situation. “Once again,” Mr. Lewis observed in his memoir, “I was accused of not being black enough.” The project, reduced in scale, was approved. The cost for Mr. Lewis: outsider status throughout his five years on the council.

In 1986, when Mr. Lewis again sought the Democratic nomination for the 5th Congressional District seat, his opponent was state Sen. Julian Bond, once SNCC’s publicist. Bond was considered the prohibitive favorite.

Tall, handsome and charismatic, Bond was a celebrity. “Saturday Night Live” had him as a guest host. Cosmopolitan magazine anointed him one of America’s 10 sexiest men. He was a lecture circuit star. Profiles described Mr. Lewis as squat, scowling, wooden, humorless.

Atlanta’s black establishment flocked to Bond. So did prominent outsiders, including then-Washington Mayor Marion Barry, comedian Bill Cosby, actress Cicely Tyson and Edward Kennedy.

Mr. Lewis campaigned tirelessly, urging that citizens “vote for the tugboat, not the showboat.” He won by four percentage points because whites — particularly Jews — gave him overwhelming support. The acrid campaign corroded his once-strong friendship with Bond.

When Mr. Lewis arrived on Capitol Hill, the New York Times observed wryly that he was one of the few members “who must deal with the sainthood issue.”

Mr. Lewis was a nominal member of the Democratic leadership as senior chief deputy whip, but he was rarely involved in nose counting or legislative detail. Former congressman Alan Wheat (D-Mo.), a colleague in the Congressional Black Caucus, said in an interview: “John’s biggest strength in the House was to motivate people, to gather impetus for key measures. He used his standing as a cultural icon for good causes, never for personal benefit.”

On both social and economic issues, Mr. Lewis lived up to the label he put on himself: “off-the-charts liberal.” Like other members of the Black Caucus, he consistently opposed domestic spending cuts. But he was just as vehement in his opposition to the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, although many blacks — particularly Georgians — disagreed.

Unlike some other black notables, Mr. Lewis refused to participate in Louis Farrakhan’s 1995 Million Man March in Washington. He also denounced Farrakhan’s anti-Semitic rants. When needled about racial loyalty, Mr. Lewis liked to say, “I follow my conscience, not my complexion.”

In 2010, Obama awarded Mr. Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor. He continued to say that his conscience demanded that he teach young people the legacy of the civil rights movement. In 2013, he began a trilogy in comic book form called “March.” When a former supporter of the Ku Klux Klan named Elwin Wilson popped out of history in 2009, asking forgiveness for having severely beaten then-Freedom Rider Lewis in 1961 at a Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill, S.C., Mr. Lewis took him on three TV shows to show that “love is stronger than hate.”

He revisited the Edmund Pettus Bridge on anniversaries of Bloody Sunday, often accompanied by political leaders of both parties. “Barack Obama,” he mused, “is what comes at the end of that bridge in Selma.”

John R. Lewis, a civil rights titan and a formidable member of Congress for three decades, died at the age of 80 on July 17. (Zach Purser Brown/The Washington Post)

This article was originally published by The Washington Post