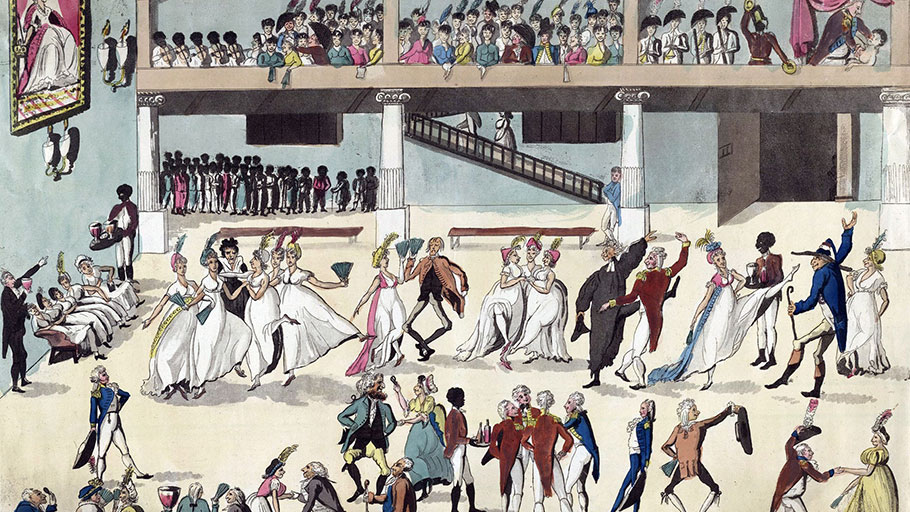

A contemporary rendition of British colonists served by African slaves at a ball in Spanish Town, Jamaica, between 1800-1809. Photograph: Everett Collection Historical/Alamy

The modern equivalent of £17bn was paid out to compensate slave owners for the loss of their human property. Some people believe we should be proud.

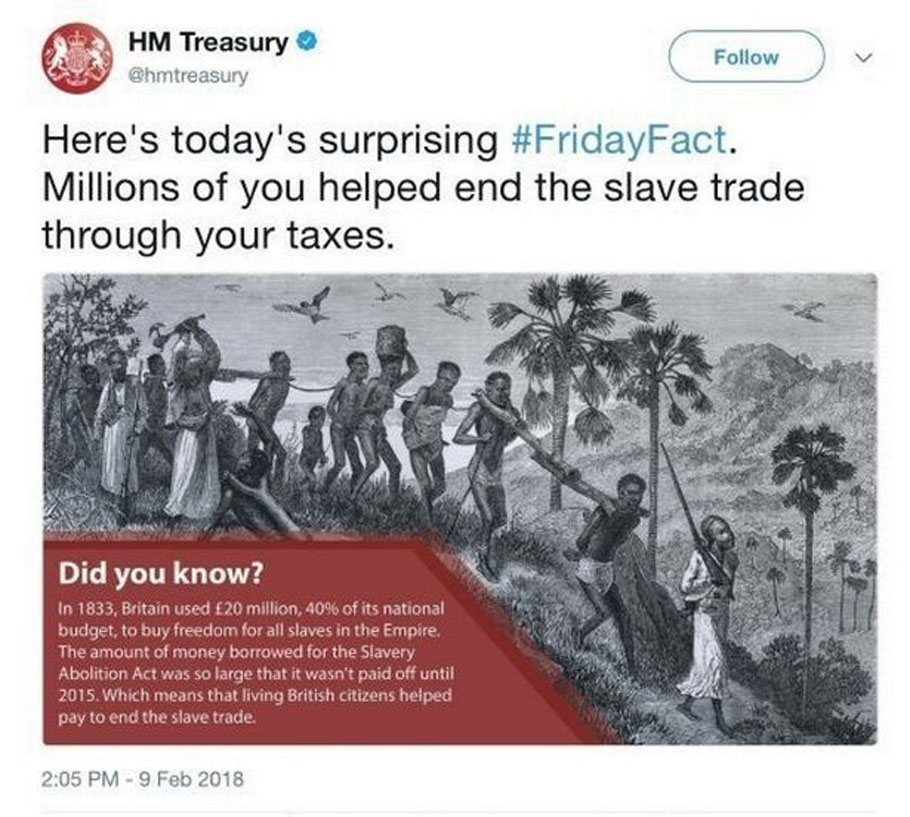

It is hard to imagine why somebody at the Treasury thought that the subject of slavery was fertile territory from which they might harvest their weekly “surprising #FridayFact”. Just after lunchtime on 9 February the department’s Twitter page presented its third of a million followers with its latest offering. “Millions of you helped end the slave trade through your taxes,” it trumpeted.

Below, under an image of Africans being marched, in yokes and ropes, into slavery, the tweet continued: “Did you know? In 1833, Britain used £20 million, 40% of its national budget, to buy freedom for all slaves in the Empire. The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Abolition Act was so large that it wasn’t paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.”

The “fact” had the unctuous feel of a pat on the back. A little over a week after millions had been given their self-assessment tax bills, the good people at the Treasury threw us something to cheer us up. You might be skint, you might want to weep when you see your bank balance but look, you helped to end slavery, at least it’s all for a good cause, eh?

What the Treasury didn’t mention, though, was that the £20m was paid out to the 46,000 slave owners, to compensate them for the loss of their human property. By one calculation that is the modern equivalent of about £17bn. Is this really something we should regard with collective pride?

Few people in the 1830s would have seen it that way. Compensation was a mechanism by which Britain was finally able to end a system that millions of people had come to regard as abhorrent, and a national disgrace. It was a way out. The abolitionists agonised over it. To accept the principle of compensation was at odds with their fundamental moral position: that it was impossible for one human being to own another, to hold “property in men”, as they put it. The only people who saw the payment of compensation as a positive were the people who had spent three decades campaigning for it and would be the beneficiaries of it – the slave owners.

Screenshot of the Treasury tweet, which has now been deleted.

And the slave owners not only received compensation from the British taxpayer, they won another concession, the euphemistically titled “apprenticeship” system. What this meant was that the slaves themselves were forced to work the fields for a further six years after the supposed abolition of slavery – 45 hours a week for no pay.

Within hours of the Treasury’s tweet being posted it was evident that surprise was not the dominant emotion it was eliciting. Anger and incredulity were more in evidence. Lexington Wright tweeted: “So basically, my father and his children and grandchildren have been paying taxes to compensate those who enslaved our ancestors, and you want me to be proud of that fact. Are you f**king insane???”

To pay the £20m to the slave owners, the government set up the Slave Compensation Commission, which like all bureaucracies left behind detailed records of its financial outgoings. By accident, the process of compensation created a nearly complete census of British slavery: the names of all the slave owners on 1 August 1834, the day on which slavery ended – and of course “apprenticeship” began. This is how we know the scale of slave ownership of the so-called plantocracy, the super-rich of their age: men such as John Gladstone, the father of prime minister William Ewart Gladstone.

The Gladstones were paid £100,000 – the modern equivalent of about £80m – in compensation for 2,500 men, women and children they regarded as property. Also in the records of the Slave Compensation Commission are the ancestors of George Orwell, Graham Greene, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Gilbert Scott and David Cameron – all owned slaves and received compensation. All of this information is publicly and freely available on the website of the University College London’s Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project.

Although called a #FridayFact, what we are dealing with here is a factoid: a fact-like entity that crumbles on proper examination. It was not only wrongly judged, in numerous respects it was just wrong. Compensation was not paid at the end of “the slave trade”. That ended in 1807. The slave trade and slavery – confusing as that may be to us – were regarded almost as separate issues at the time. Compensation was paid 30 years later, at the end of slavery.

To make matters worse, the picture chosen to illustrate the #FridayFact was (again) of the slave trade rather than slavery; and, judging by the dress of the slave traders depicted, it was a Victorian image of the eastern slave trade, through which Arab and African-Arab slave traders trafficked millions of Africans to lives of enslavement in the Middle East – a too often neglected aspect of the global story of slavery.

Even the most essential details were wrong. The 1833 act did not free “all slaves in the Empire”, as the most rudimentary research would have shown.

Someone at the Treasury wisely deleted the tweet within hours. Yet its inaccuracy shows what happens if we as a nation focus on abolition but stay largely silent on the centuries of slave-trading and slave-owning that predated it. It is what happens when those communities for whom this history can never be reduced to a Friday factoid remain poorly represented within our national institutions.

David Olusoga is a historian, and presented the BBC Two documentary Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners