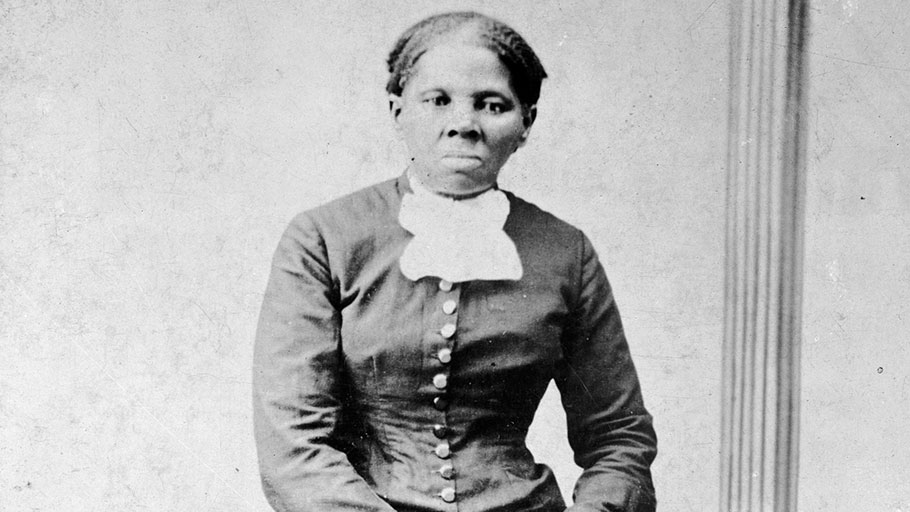

Part 1. This is in homage to Nana Harriet Tubman: African woman, Black and beautiful woman; fierce and fearless freedom fighter; womanist warrior for all the people, up all night with her weapon on her knee, waiting for the day to dawn; the relentless and transformative fire that finds and makes a way for itself wherever it goes; thunder-while-sitting-and-thinking-freedom; broad-shoulders ancestor, tall and unmovable like a mountain; honored leader, tireless liberator, and inexhaustible light, opening and making clear the way to freedom and an uplifted life for our people and an expanded and inclusive realm of freedom in this country and the world.

I am thinking, wondering and working my way through how we can talk about Nana Harriet and our history, the sacred narrative of our people, in alternative and expansive ways. It is not enough to talk about her as an American hero or heroine, an American idol or legend. Indeed, such a designation can be not only diminishing, but also misleading. It is diminishing because it’s a shorthand way of summing up her life as being American and suggesting that is the best way to understand and honor her and her achievements. But in fact, her relevance and achievement extend beyond America, not only to the world African community, but also to the whole of humankind and the ongoing struggle for human freedom and other human goods.

Moreover, to use the simple designation American, instead of African or African American is misleading and tends to hide her real identity, separate her from her people who brought her into being, taught her faith, freedom and self-freeing, and opened a path and practice of righteous and relentless resistance from the beginning that she could continue on and lead others on, along this long, difficult and demanding way to freedom. In addition, such an Americanization hides the horror of the Holocaust of enslavement, the brutish and bloody killing field and battleground of our struggle on arriving here, whose pathological legacy of systemic racism lingers on like long COVID, continuously crippling and killing our people and others similarly situated and oppressed.

Also, such a designation and Americanization appropriates our history, foregrounds and claims it for a continually oppressive society, using it to praise America, rather than to question, critique and condemn its wicked and radical evil ways and welcome radical and rightful transformation. And of course, such dishonest appropriation hijacks and assimilates in Borg-like fashion the rightful praise of Black people who have compelled and contributed definitively to the expansion of the realm and practice of freedom and justice in this country and the world. Already then, we have begun to talk about Nana Harriet in alternative and expansive ways rather than recounting the common American fare of diminishment, falsification, appropriation and rancid bad faith.

As part of this engaging the life and legacy of Nana Harriet I want to focus especially on the beauty and good of her hearing heart and amazing mind. In the Husia, Seba Amenhotep, son of Hapu and Itu, says in his moral self-presentation that he is a man of wisdom, excellent in character and counsel and that he has a hearing heart in his relations and dealing with the people. It is in imitation of the Divine, for the sacred teachings of ancient Egypt say God is a hearing God who hears the prayer and petition of the poor and unpowerful, sick and suffering, the have-nots and the needy and comes at the voice of the caller. And Nana Harriet models and mirrors this eminently moral posture and practice

Now, a hearing heart in the Kawaida Ma’at tradition is a central moral concept and virtue. Derived from the word sedjem, in ancient Egyptian means to listen, hear and comply and this in Kawaida translates in the following way. To listen is to give rightful attentiveness; to hear is to have empathetic understanding and to comply is to act appropriately, i.e., according to what is requested or required. And again, this how Nana Harriet live her life, did her work and wage the liberation struggle. Nana Harriet clearly listened to their cry for freedom and to the end of the savage forms of suffering imposed on them; she heard them, felt them, saying “I have heard (my people’s) groans and sighs and seen their tears”, and she acted appropriately, defiantly declaring “I would give every drop of blood in my veins to free them”. In a word she offered her life and her death as a willing sacrifice to free and serve them.

She, thus, is not a “I got mine; now you go get yours”, vulgarly individualistic kind of person. She understands herself in the midst of family and community, sees and teaches by the way she lives her life, does her work and wages the struggle that freedom is indivisible and a collective process and practice of self-determination in and for community. It is for her a shared good, collectively fought for and cooperatively achieved. Certainly, there is no doubt Nana Harriet is a liberator par excellence, but in this amazing collaborative mind and work of hers, each person is a self-emancipating participant in their own liberation.

Nana Harriet opens the way, and shows the way, but the people must, themselves, summon and sustain the consciousness of freedom and the courage of resistance to take the road and stay the route to freedom. And they must stand strong in the storm of nagging uncertainty, apprehension and threats of death and not betray her trust in them or betray themselves and their commitment she asked of them to “go free or die”.

What I am arguing here is that Nana Harriet, the rightfully legendary liberator, does not simply free an enslaved and passive person, but enables them to become self-conscious agents of their own lives and liberation. And this is best understood as a cooperative freeing, a collaborative emancipation and a collective liberation. Again, Nana Harriet showed the enslaved Africans the way to freedom with all its cautions and contingencies, committed herself to lead them on this dangerous and demanding road and to teach them the practice of self-freeing.

And this self-freeing she assures them is not a simple escape, a thoughtless running way, but an act of agency requiring due reflection and determined choice. For the practice and achievement of freedom requires we consider not only the existential necessity and good of freedom but also the possibility and consequences, of being captured or killed for daring freedom, and even the challenges freedom itself brings. And given all this and other related concerns, those who want freedom must choose freedom over enslavement, the certainty of savage oppression, end enslavement or the nagging apprehension and unknown possibilities of freedom.

This brings us to lessons from Nana Mary McLeod Bethune and Nana Frantz Fanon on the importance of leader’s faith in their people and the obligation and critical contribution of self-freeing. For in Nana Harriet’s life, work and struggle and that of her people, we have a model and mirror of this. Nana Mary McLeod Bethune says, “the measure of our progress as a race is in precise relation to the depth of the faith in our people held by our leaders”. And Nana Frantz Fanon says, “an authentic national liberation exists only to the precise degree to which a person has irreversibly begun his own liberation”. And again, thus it is with our Nana Harriet and our people exercising the right and responsibility to be free, flourish and come into the fullness of themselves.