By Kelebogile Zvobgo —

Between 1850 and 1950, thousands of African American men, women and children were victims of lynchings: public torture and killings carried out by white mobs.

Lynchings were used to terrorize and control black people, notably in the South following the end of slavery.

Yet despite the prevalence and seriousness of the practice, there has been an “astonishing absence of any effort to acknowledge, discuss, or address lynching,” reports the Equal Justice Initiative, the leading organization conducting research on lynchings.

Until now.

In April 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice – the first lynching memorial in the U.S. – was opened in Montgomery, Alabama. In December of the same year, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a bill that defined lynching as a federal crime.

More recently, in April 2019, the state of Maryland established a truth commission to investigate the lynchings of at least 40 African Americans between 1854 and 1933.

The legislation that authorized the truth commission, Maryland HB 307, was sponsored by Maryland House Delegate Joseline Peña-Melnyk.

Speaking before the House Judiciary Committee in February 2019, Peña-Melnyk said that the commission would be an opportunity “to send the message that the lives of the 40-something people really mattered.” Written with the help of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project and endorsed by the Equal Justice Initiative, the bill passed with strong bipartisan support just two months later.

The commission has the potential to educate the public about dozens of lynchings – some of which occurred with the knowledge or direct involvement of local, county and state government entities. The commission can also provide the opportunity for reconciliation between the families of those who were responsible and the families of those who were killed.

Can it live up to its promise?

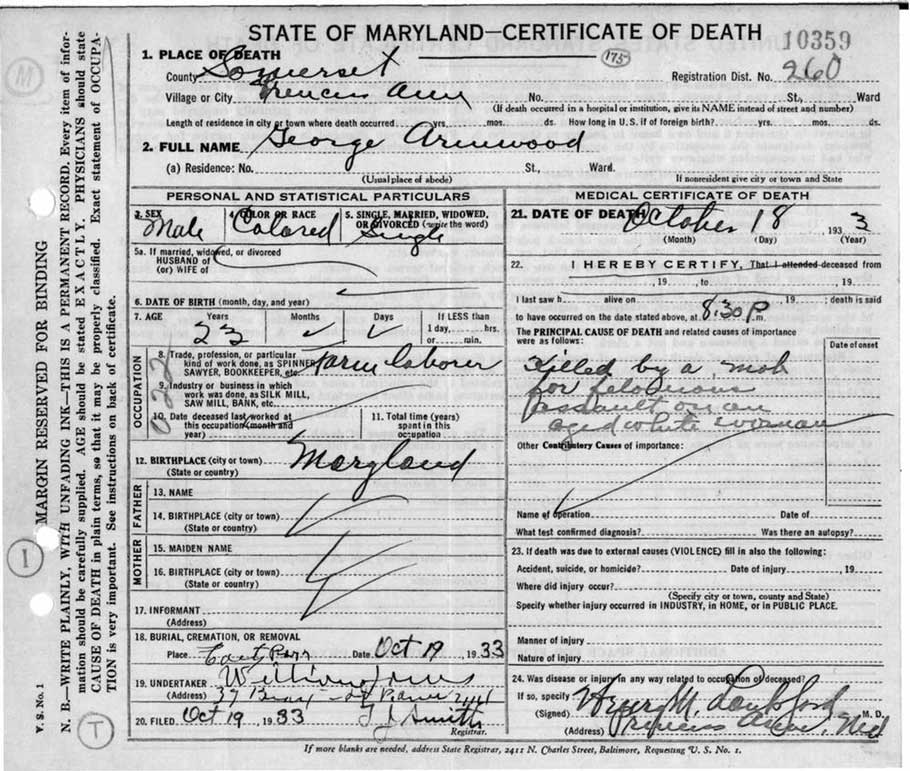

Death certificate for George Armwood, 22- or 23-year-old lynched in Maryland by a mob. Maryland State Archives/Flickr

Truth commissions around the world

I study human rights, with a particular interest in institutions that hold individuals, organizations and governments accountable for human rights abuses. My current research focuses on truth commissions and how they can be designed to be effective.

A truth commission is a temporary body that investigates different forms and systems of violence that happened in the past. Examples include the commissions that investigated apartheid in South Africa, the civil war in Timor-Leste and the dictatorship in Chile.

Generally, governments establish commissions to examine documents and collect witness testimony. A key goal of commissions is preparing a report that details the facts and traces the legacies of violence and abuse. A second, related goal is reconciliation. In Maryland’s case, this would mean working toward respect, understanding and trust of those of other races and their experiences.

Based on my research and analyses of truth commissions in Chile, South Africa and Timor-Leste, I believe that the commission in Maryland has the potential to succeed.

But it faces some big obstacles.

Truth commissions in the US

The commission in Maryland will not be the first in the U.S.

In the 1980s, a national commission studied the government’s relocation and internment in camps of people of Japanese ancestry during World War II. The commission’s work led to both apologies and reparations for victims.

In addition, there have been commissions at the local level – for example, the 2004 commission in North Carolina that examined the killing of five anti-Ku Klux Klan demonstrators in Greensboro in 1979. There have also been commissions at the state level – for example, the 2013 commission in Maine that investigated the separation of indigenous Wabanaki children from their communities since 1960.

However, the commission in Maryland will be the first to research lynchings, which investigative journalist Ida B. Wells in 1909 called the U.S.‘s “national crime.”

The truth commission in Maryland

The Maryland law establishing the commission calls for “full knowledge, understanding, and acceptance of the truth.”

How would a commission accomplish this?

I have found in my research that a commission needs support from politicians, access to information, and community knowledge and involvement. It appears that the commission in Maryland has – or will have – each of these characteristics. In this regard, it is similar to previous successful commissions.

First, similar to South Africa, the commission has support from politicians on both sides of the aisle – in this case, Democrats and Republicans. Bipartisan support affords the commission public legitimacy as it seeks access to court records, historical archives, and local and statewide newspapers. So, it may be harder to politicize the commission’s work.

Second, as in Timor-Leste, where the commission held hearings in the villages where violence occurred, the commission in Maryland will hold hearings across the state, including in communities where lynchings occurred.

By operating throughout the state, the commission can more easily reach victims’ descendants and collect their stories. Collecting information from as many sources as possible is important to ascertain the truth.

In addition, the commission will be well positioned to broadly share its work and findings, through the hearings themselves, local news reporting and more. This is key to both truth and reconciliation.

Third, as in Chile, the commission in Maryland will receive recommendations from the public, including from victims’ families, about erecting memorials and historical markers where lynchings occurred.

Getting families and the wider community involved in this aspect can help provide healing and closure. For more than a century, the pain and trauma they experienced went unacknowledged.

Now, not only does Maryland have the potential to address this pain and trauma, it has the opportunity to memorialize the lynchings so others, too, can know what happened.

Obstacles to truth and reconciliation

There are, I believe, obstacles that may prevent the commission from accomplishing all of its goals.

To start, the commission’s limited focus may lead to limited reconciliation. Lynchings represent just one form – the most extreme form – of race-based discrimination and violence.

Other forms – which persist today – include the over-policing, over-criminalization, and mass incarceration of African Americans. The commission hasn’t been designed to address these issues or the broader context of racism and violence. So, it’s unclear how the commission will lead to widespread reconciliation.

In addition, while the families of those responsible for lynchings can work with the commission and take the opportunity to make amends to the victims’ families and communities, they may decline to do so. And victims’ families may not be prepared to forgive.

Finally, the commission has been created in a fraught social and political environment. Hate crimes have increased in recent years throughout the U.S. Some elected officials have trivialized racial violence – including lynchings. And some race-focused policies, such as reparations, are widely unpopular among Americans.

So, while the commission benefits from broad support from government leaders in Maryland, it may not enjoy similar support from the public.

Whether the obstacles I describe will overcome the strengths of the commission remains to be seen. Nevertheless, the commission represents an important first step and offers a guide for similar efforts in other states.

This article was originally published in The Conversation