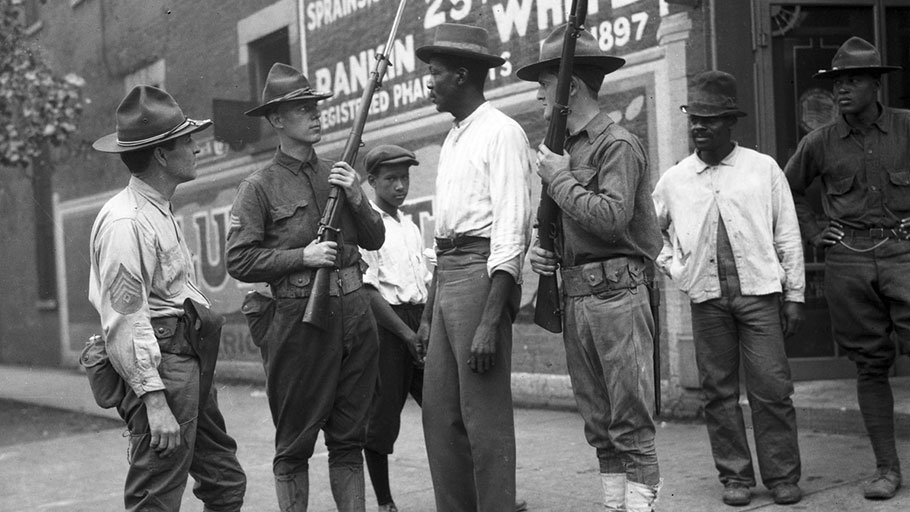

National Guard during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots. Photograph by Jun Fujita, courtesy of Chicago History Museum.

Note: this essay quotes a sign attached to the body of a man lynched in 1919, which uses a racial slur.

HBO’s recent release of a prestige adaptation of Philip Roth’s 2004 novel The Plot Against America makes it worthwhile to examine whether fascism is really so alien to the United States as many wish to believe. In Roth’s novel, a Jewish extended family in Newark experiences fascism’s arrival in America, with the 1932 election of Charles Lindbergh to the presidency, as an intrusion of European extremism against an American Way—and a short-lived one, at that. When many white thinkers ponder Roth’s Plot or the sardonic title of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, they often miss the many ways in which it has already happened here. After all, the public prominence of the Ku Klux Klan and the massive riots that rock the climax of Roth’s novel were already regular features of American life, depending upon where you lived. For example, in early May 1927, just a few weeks before the historical Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field in the Spirit of St. Louis, some 5,000 whites rioted in the black business district of Little Rock, Arkansas, where they burned the body of man named John Carter. Local police officers, many rumored to be Klan members, did nothing to stop the violence—and may have even taken part.

Black observers of current trends, however, tend to be a little more astute. For example, in his February 21, 2020, New York Times column, Jamelle Bouie argues that the expansive authoritarianism of Donald Trump has its analogue in the Jim Crow South. However, we should not consider the Venn Diagram of fascism and Jim Crow as a circle. The reality is a little more complicated.

The word “fascism” has also long been employed as a political Rorschach blot. As early as 1946, just one year after the end of World War II, George Orwell was complaining of this fact in his essay “Politics and the English Language,” writing: “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable.’” But let us take this as a working definition:

Fascism is the attempt, birthed in reactionary politics, to resolve the contradictions of democracy for purposes of preserving elite power against the demands of the masses.

This will need some explanation. Although we today associate democracy with high ideals, its origins are a bit grubbier. For example, opposition to the Angevin kings of England (which led to the Magna Carta) included, according to historian Robert Bartlett, such charges as “heavy taxation, elevation of low-born officials, slow and venal justice, disregard for the property rights and dignities of the aristocracy.” Much of the Magna Carta focuses upon preserving the property rights and prestige of the aristocracy while limiting the king’s ability to levy certain taxes without “the common counsel of the kingdom.” The eventual emergence of a mercantile class in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance sparked another expansion of “democracy,” as the bourgeoisie sought similar privileges in order to protect their own wealth. With industrialization, and the eventual concentration of the lower classes into cities, the emerging proletariat began to press for access to the franchise itself on both sides of the Atlantic, as exemplified in the UK by the Reform Act of 1832 and in the US by Jacksonian democracy and the removal of property qualifications for the vote.

At each step in the expansion of democracy, those who already possessed the franchise feared the loss of their power and wealth by allowing any “lower” classes the privilege of voting. The United States has been much more a racial society than a class society along the lines of the UK, and so here it was easier to get elite buy-in to the idea of universal male suffrage, so long as those males were exclusively white. The abolition of slavery and the expansion of suffrage to those former slaves and their eventual descendants provoked the rage of the south’s idle landlords, who initiated a campaign of violence in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War in order to return to the status quo ante of black servitude and submissiveness. What historians call the first Ku Klux Klan was an elite project to scuttle the political empowerment of African Americans.

The “contradictions of democracy” can be seen in this struggle between those who believe that republican government should preserve elite power and the democratic desire that all citizens be given a voice in how they are governed. Fascism is an attempt to short-circuit this tension through the advancement of a purely corporate figure who is cast as the savior of “the people,” not by empowering them but rather by emphasizing his own unique attributes to act on their behalf. As the Israeli scholar Ishay Landa points out in The Apprentice’s Sorcerer: Liberal Tradition and Fascism, while fascism regularly employs the rhetoric of collectivism, it centralizes such collective and democratic yearnings upon the individual strongman leader, so that he becomes democracy personified, the one true spokesman for “the people,” who no longer need engage in self-governance.

But there is more to it. As historian Aristotle Kallis observes in Genocide and Fascism: The Eliminationist Drive in Fascist Europe, fascist ideology was born with the specific aim of seeking redemption from recent “humiliations” by latching onto the glories of the past to drive a new utopian future. This “redemption” manifested itself externally, through expansionist policies of conquest, and internally, through a “cleansing” of the population aimed at eliminating those figures responsible for recent humiliations: socialists, communists, Jews and other minority groups. The drive to “cleanse” the state, Kallis writes, “helped shape a redemptive licence to hatedirected at particular ‘others’ and render the prospect of their elimination more desirable, more intelligible, and less morally troubling.”

This has been just a brief overview, but it allows us to draw some parallels between fascism and Jim Crow. Both fascism and Jim Crow were means of limiting democratic participation and thus the political and economic emancipation of certain “others.” And both fostered a “license to hate” that resulted in massive violence against the enemies of the elite. But there are more parallels. As Landa writes in Fascism and the Masses: The Revolt against the Last Humans, 1848–1945, “Rhetoric of honoring labor aside, the Nazis strove to achieve the exact opposite: keeping wages low and increasing working hours, which was precisely what German business was insisting should be done throughout the years of the Weimar Republic.” Much the same held true in the Jim Crow South, where particular ire was reserved for those who resisted the southern tradition of racialized economic exploitation. In June 1919, after Clyde Ellison refused to work for Lincoln County, Arkansas, planter David Bennett for a mere 85 cents a day, he was hanged from a bridge, with a sign attached to his body reading, “This is how we treat lazy niggers.” Later that year, and not too far away, white mobs and soldiers would slaughter untold numbers of African Americans, in what has become known as the Elaine Massacre, for daring to organize a farmers’ union.

Although both fascism and Jim Crow constituted violent means of securing elite power, there are important distinctions to note. While southern states had their share of demagogues, Jim Crow was a multi-generational project of the Democratic Party, one not centered upon any particular individual. Too, while both fostered a “license to hate” against racial and ideological others, the Jim Crow project made a distinction between “good negroes” who “knew their place” and “bad negroes” who sought the privileges reserved to whites. The latter may have to be killed, and the region “cleansed” of those “outsider” whites who spread dreams of equality, but black people who were dutifully submissive could be tolerated in so far as their unpaid or underpaid labor created the region’s wealth.

Back in 2004, The Plot Against America was widely regarded as a commentary about the administration of George W. Bush. No doubt, the 2020 television adaptation will be viewed in the light of Donald Trump, whose rhetoric and policies have been compared by critics to both fascism and Jim Crow. Perhaps the television series will exhibit a more sophisticated understanding of fascism and America than did the book. Perhaps not. Either way, the series should provide a good opportunity for historians to educate the public on who, exactly, lay behind the centuries-old plot against all Americans.

This article was originally published by History Network News.

Guy Lancaster is the editor of the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas, a project of the Central Arkansas Library System, and is the author of Racial Cleansing in Arkansas, 1883–1924: Politics, Land, Labor, and Criminality and editor of Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950.