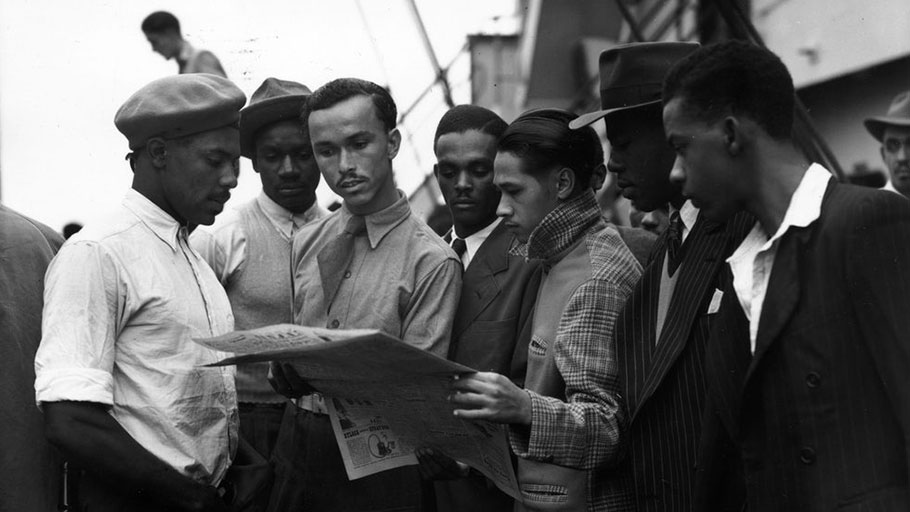

Jamaican immigrants aboard the “Empire Windrush” in 1948. (Douglas Miller/Keystone/Getty Images)

By Kaila Philo, The New Republic —

Seventy years ago today—June 22, 1948—a passenger ship carrying 492 Jamaican immigrants arrived in Essex, London. The Empire Windrush was the first of many ships to come, as the British government recruited migrants from the Caribbean Commonwealth to help rebuild the economy after World War II. These arrivals came to be known as the Windrush generation. “It is unclear how many people belong to the Windrush generation, since many of those who arrived as children travelled on parents’ passports and never applied for travel documents—but they are thought to be in their thousands,” according to the BBC.

These immigrants, now elderly, are legal UK residents. But since last year over 5,000 of them found themselves homeless, unemployed, denied health care, or deported altogether as a result of Theresa May’s “hostile environment” policy, which requires employers, landlords, banks and the National Health Service to conduct visa inspections. In April, high commissioners from all of the Caribbean Commonwealth nations rebuked the UK government over the scandal, the British home secretary resigned, and the Home Office assembled a Windrush task force. In a more symbolic gesture, the government designated today, June 22, as “Windrush Day.”

The New Republic spoke to Trevor Phillips, the former head of the British Commission for Equalities and Human Rights and co-author of 1999’s Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multiracial Britain, about the past, present, and future of the Windrush generation—of which he is a descendant.

How were the Windrush immigrants greeted in the UK?

Bear in mind that, at that time, the word “immigration” didn’t have quite the same meaning, or didn’t carry the same weight. All of these people carried British passports because they were members of the British empire. There was no distinction between a British person born in Bombay, or Georgetown, or Leeds. They had exactly the same thing, and that was how people thought of it. Secondly, there were no immigration formalities. If you look at the pictures of people coming down the gangway and walking onto the dock, there are no immigration officials there demanding passports. So the status was quite different, and the numbers involved were tiny. Right through the 1950s, total immigration would’ve been measured in four figures—about 2,450 people a year.

So that’s context, and that then tells you something about why there was a sort of schizophrenic response. When it became known that a boat that was bringing these 500 or so people, the colonial office panicked and thought it was quite a large number, because the annual immigration numbers would’ve been three or four thousand. There was a lot of discussion about how they would fit in, where they would live, whether there’d be jobs for them. They even sent a warship to shadow Windrush as it came into the English Channel. There was an official anxiety not so much about immigration, but about integration. On the other hand, when the guys got here, there wasn’t too much anxiety in the street. There were welcome parties, and all that sort of thing.

Towards the end of the 1950s and ’60s, things became a bit different, partly because Britain was in transition from the war. People had put up with all sorts of things—rationing and so on—in the late ’40s and early ’50s because of the deprivations of war, but by the end of the 1950s, they were expecting a bit more. There were conflicts over housing—particularly in cities like London and Nottingham—and at first, what you might call full-fledged race riots happened in Northwest London, like in Notting Hill in 1968.

That was dressed up as a conflict between young men with not enough to do and teddy boys and so on, but it was really about housing—who’s got homes and who couldn’t get homes. There was a lot of resentment about the fact that some of the Windrush generation had come to Britain, couldn’t get municipal housing, and weren’t put into public housing, so they saved up and managed to get themselves rented housing. Some started to buy housing.

Why did this general attitude change over time?

War ended in 1945. By 1957-58, the population was expecting a bit better, and they were rather cross that things weren’t moving faster. So the immigrants received a bit of the backlash from that. And the other thing that’s made quite a big difference—and this is a generational point—is that the first group that came from 1948 to 1950 were mainly men. They were mainly male, but women followed. And so what then followed? Children. A lot of people, of whom I’m one—and I’m probably one of the early ones of Caribbean heritage, who were born in the mid-1950s and late-1960s—by the early 1960s, these children turned up in schools.

When they started seeing these people at the school gates, they realized that these people they thought were just coming for a while, because they couldn’t get jobs back home. Like my parents, they thought they’d come, make a bit of money, save up, go home, build a house, and become, by colonial standards, middle-class. Well, what happens when people like me start turning up at schools is that people start realizing rather quickly, that isn’t going to happen. Nobody’s going home.

It’s at that point I think that sentiment starts to change because you then have to address a different population. You then have to worry about things like discrimination, which not too many were worried about, because people who weren’t liberal couldn’t care less and people who were liberal didn’t like it but thought, “Oh, well, it’s not going to be an issue for very long because they won’t be here for very long.” And then everybody realizes it’s going to be a permanent question. So that’s why you get, in 1955, the first anti-discrimination law.

Some of the Windrush generation’s immigration records have been destroyed by the government. How can they attain citizenship without them?

The government is going to have to work a bit harder here. They’re going to have to do some investigation. Almost all of these people will probably belong to one or two churches; most of them will have belonged to the same church for their whole life. I was christened in a church about 20 minutes from where I live now; if and when I keel over, I’m going to be buried in that church. So somewhere in the church records, there will be my christening, my Sunday school attendance, all of that.

My idea is that what they can do instead of putting the whole burden on the person concerned to dig out all kinds of official documents that have probably been shredded and not digitally recorded, is to allow some latitude to present some kind of records—or to get a letter from your minister. Some of the women will have records pertaining to their hospitalization from giving birth.

I think the government would make it less difficult if they, first of all, said that there’s a presumption of innocence. Right now, there’s a presumption of guilt: Unless you can produce all these documents, you must be illegal. Well, I think they ought to just simply reverse that, and state a presumption of innocence, unless someone can demonstrate that you weren’t where you say you are. And secondly, if there is some doubt, then the government ought to agree to allow a wide array of documentation than the Home Office currently allows. They’re definitely thinking along those lines.

Do you think the rise in anti-immigrant sentiment is anomalous, or the beginning of a broader cultural shift?

Public opinion has really come down very firmly on the side of the Windrush migrants. That is the thing that would be most striking. Most people in this country—whether they’re in government or not, whether they’re right or left—would always have assumed that British people, at best, didn’t care very much about what happened to a bunch of old black people and, at worst, would’ve assumed that they would be hostile to anybody who appeared to be breaking immigration laws. That’s the thing that’s most surprising: the wave of public indignation about the treatment of these people.

So I don’t really buy the idea that the Windrush scandal demonstrates that there’s a growing anti-immigration sentiment; I’d go as far to say the opposite, in fact. If you look everywhere else in Europe, exactly the opposite of what happened here is taking place. In Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Italy, there would never have been this wave of public support for immigrants who’ve been treated in this way.

I think the anomaly here is that Britain is in a completely different mood to the rest of Europe. To be frank, people who tell you that there’s this great wave of anti-immigrant sentiment here are saying that because that’s what they would like to believe, and they want to be the people who save black folks, and fight for all rights and all of that. This country isn’t like that at all—that’s why you’ve heard of this scandal.

If you were to update your book with a new chapter, what would it say?

Ah! Very interesting question. I have a very particular answer to that, which might take quite a bit of explaining to an American audience, but let me put it this way: The most interesting thing about the Windrush story right now is that although the scandal is current, it isn’t the most important thing that has happened. The most important thing is about to happen. Somewhere in the next decade or 15 years, something is going to happen in Britain that isn’t happening anywhere else in Europe, and hasn’t happened anywhere in the Americas.

If you refer to a person of Caribbean origin in Britain right now, you tend to be talking about somebody who’s got two black parents, two Caribbean parents, like me. Both of my parents are from British Guiana. Somewhere between now and 2030, the majority of people of Caribbean origin will either have a white parent or a white grandparent. That’s quite a substantial thing; it’s the fastest growing demographic group in the UK. And I think it is, as a phenomenon, unprecedented. There are lots of people who have mixed heritage in South Africa and the United States and Brazil, but for the most part, that is the result of slavery and oppression and rape. It is very unusual to have a group this size of mixed people of dual heritage, which is the result of free choice.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Kaila Philo has written for The Baffler, The New Inquiry, Vice, and Full Stop. Follow Kaila Philo on twitter — kailanthropie