The instant the news flashed that Congressman John Lewis died the expected and much deserved avalanche of tributes poured in from all corners. Trump’s tribute was in that avalanche. The tributes all pretty much followed the same pattern. Lewis was praised as a civil rights icon, courageous, unremitting, and a historic example of how a life devoted to civil rights can result in monumental changes in how America deals with race and racism.

Lewis was, of course, all of that. But he was much more and that much more culminated in not the speech that he gave at the 1963 March on Washington that rocket launched his name to national awareness. Rather, it was the speech that he didn’t give that set the tone for Lewis, that era, and this era.

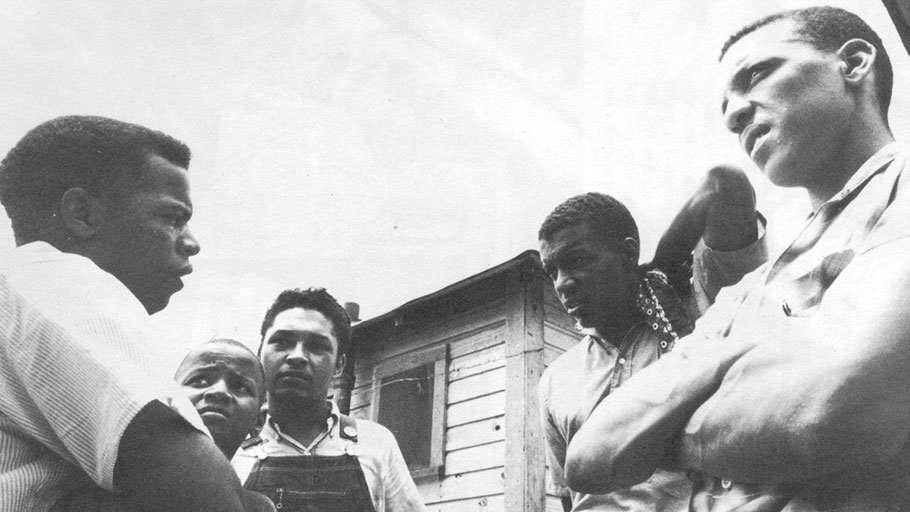

Lewis was invited to speak because he was chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. SNCC was on the frontline of the civil rights movement, doing the hardest, dirtiest, and most dangerous work in backwater Klan ridden and dominated Southern towns. SNCC organizers were the ones who pushed the envelope on voting rights. They were the ones who provided much of the grunt work for MLK and the other established civil rights organizations in those same backwater towns.

But in the months before the March, SNCC had already begun to sharply pivot toward radicalism. They were beginning to loudly declaim not just voting rights denial, and racist sheriff and registrars, but capitalism. They embraced liberation movements in Africa and Asia, denounced the troop escalation in Vietnam, and poverty. This was way too much for the moderate, mainstream, civil rights organizations and they began to quietly inch away from SNCC’s organizing tactics, methods, and politics. That inch in time would become a stampede away from SNCC. They would vehemently denounce the organization.

Lewis was caught in the middle. He was never all in for SNCC’s sharp shift to anti-capitalist radicalism, and all out tout of Liberation movements. However, some of this talk did appeal to Lewis. That set the stage for the speech he planned to give at the March and that ignited the wild, frantic, efforts by the moderates to derail that speech. There was much public and behind the scenes wrangling, threats from some civil rights leaders and moderate churchmen to boycott the March. The Kennedy administration virtually demanded that Lewis scrap the speech.

Lewis wobbled. He agreed to give the speech but make the cuts that drove the critics crazy with fear about infuriating the Kennedys. The speech he gave was hardly moderate, timid, and milk sop. It punched the right buttons about militant protest, and the end game of the civil rights movement to obliterate segregation. However, what was butchered out, was the visionary tone in the speech for then and now.

He made clear that police abuse and violence was a major concern of SNCC and was the single biggest threat to Black rights and lives. He made clear that he and SNCC would not back the Kennedy civil rights bill if it did not include stiff penalties and enforcement for ending police violence against Blacks. This was a no-no and created panic among the moderates. However, Lewis and SNCC by making the bold call for a frontal attack by the federal government on police violence understood that without strong federal civil rights laws and enforcement of those laws against police violence South and North, Black lives would always be in mortal danger. Local prosecutors and officials would not crack down on that violence. Lewis’s compromise was that SNCC would back the bill but with “great reservations.” This was the great reservation.

The fast-evolving international liberation movements were very much on Lewis’s and the SNCC organizer’s minds. Lewis openly called for a revolution and that revolution should be aimed at breaking down the violence, poverty, and discrimination that dumped poor Blacks at the bottom of the political and economic barrel. He did not shirk from naming “the black masses” as the driving force of that ‘revolution.”

This kind of talk was absolutely anathema to the mainstream civil rights organizations. They bluntly told Lewis he could not use those incendiary words. Lewis upped the ante by talking of a scorched earth policy and burning down Jim Crow to the ground, though quickly adding “nonviolently.” It didn’t help. This smacked way too much of the left-wing radicalism that civil rights leaders feared would hopelessly taint the civil rights movement as a communist, radical, dangerous movement. The Kennedys would quickly cut and run from that.

The civil rights organizations certainly read the White House move correctly. Kennedy, Hoover, and the FBI always on the lookout for any scintilla of communist involvement in the civil rights would have had a field day with Lewis’s words. However, those words captured the mood of the Black masses for the kind of radical change that would do more than stop at the passage of civil rights laws, but demanded a frontal assault on poverty, violence, and the gaping economic disparities that shackled the Black poor. Lewis on that score got it right. He was way head of the game as time has amply proved.

This is the John Lewis that I will always remember.

This article was originally published by The Hutchinson Report