A new World Bank reports documents the continent’s impoverishment by rampant minerals, oil and gas extraction — but the bank enforces policies that feed it.

By Patrick Bond —

A new World Bank report, The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018, documents Africa’s impoverishment by rampant minerals, oil and gas extraction. Yet the bank enforces the foreign loan repayments and trans-national corporate profit repatriation that sustain the looting.

Using “natural capital accounting”, the bank derives “adjusted net savings”, to better measure economic, ecological and educational wealth. This is preferable to “gross national income” (GNI), a minor variant of gross domestic product (GDP). GNI fails to consider depletion of non-renewable natural resources and pollution, not to mention unpaid women’s and community work.

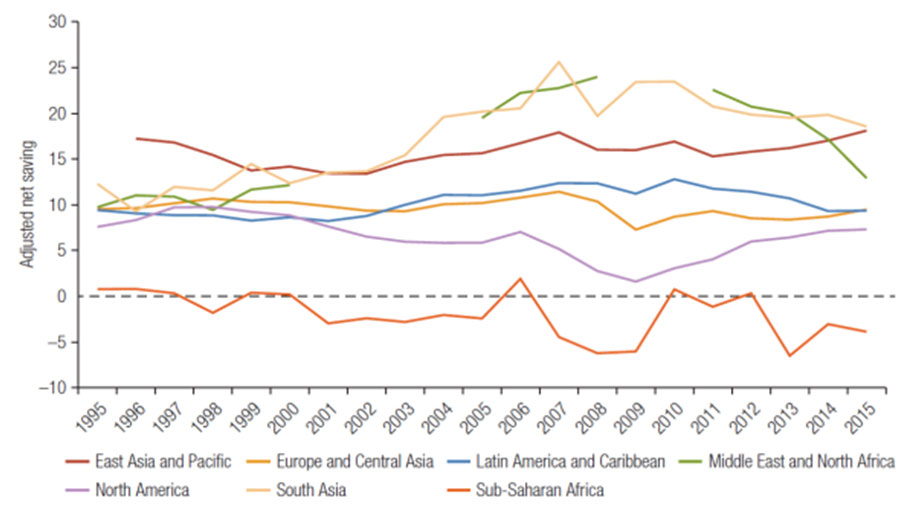

The bank concludes that Sub-Saharan Africa loses about $100bn worth of adjusted net savings annually. It is “the only region with periods of negative levels — averaging negative 3% of GNI over the past decade — suggesting that its development policies are not yet sufficiently promoting sustainable economic growth … Clearly, natural resource depletion is one of the key drivers of negative adjusted net savings in the region.”

The bank asks, “How does Sub-Saharan Africa compare to other regions?” And answers, “Not favourably.” Contrary to the “Africa Rising” mythology, the adjusted net savings decline was worst here from 2001-09.

Source: World Bank calculations. Note: There is a break for Middle East and North Africa because of a lack of data for many countries in the region for those years.

Attracting foreign direct investment in mining is counter-productive. The bank concedes, “Especially for resource-rich countries, the depletion of natural resources is often not compensated for by other investments. The warnings provided by negative adjusted net savings in many countries and in the region as a whole should not be ignored.”

But warnings such as the 2012 Gaborone Declaration by 10 African leaders are mainly ignored. There is a simple reason, related to power. “The adjusted net savings measure remains very important, especially in resource-rich countries. It helps in advocating for investments toward diversification,” the bank notes, “outside the resource sector.”

Africa desperately needs diversification from mining, but governments remain influenced by trans-national corporations intent on extraction. Even within the World Bank such bias is evident, as the case of Zambia shows.

Zambia’s missing copper

Last year, Zambia became a pilot study within the bank’s wealth accounting and valuation of ecosystem services project. Forests, wetlands, farmland and water resources were considered “priority accounts”. Conspicuously missing was copper, the main component of Zambia’s natural wealth.

Was copper neglected because such accounting would show a substantial net loss? A decade ago, one World Bank estimate of copper’s annual contribution to Zambia’s declining mineral wealth was 20% of GNI. Discussing such data might compel Zambians to rethink their economic strategy.

Bank staff work not in Zambians’ interests, but on behalf of other international banks and trans-national corporations. From 2002-08, Zambia’s president Levy Mwanawasa came under severe privatisation pressure from the World Bank so as to repay older loans, including those taken out by his corrupt predecessor, Frederick Chiluba. That debt should have been repudiated and cancelled.

When privatising Africa’s largest copper mine, Konkola, Mwanawasa should have received $400m for Zambia’s treasury. But the buyer, Vedanta CEO Anil Agarwal, bragged to a 2014 investment conference in Bangalore how he tricked Mwanawasa into accepting only $25m. “It’s been nine years and, since then, every year it is giving us a minimum of $500m to $1bn.”

Top-down or bottom-up?

From 1990-2015 many African countries suffered massive shrinkage in adjusted net savings, including Angola (68% of its wealth), the Republic of the Congo (49%) and Equatorial Guinea (39%).

There are two ways to address trans-national corporations’ capture of African mineral wealth: bottom-up through direct action to block extraction, or top-down through reforms. The latter is exemplified by the African Union’s 2009 alternative mining vision (AMV).

It proclaims, “Arguably the most important vehicle for building local capital are the foreign resource investors — trans-national corporations — who have the requisite capital, skills and expertise.”

South African activist Chris Rutledge opposed this neo-liberal logic in a 2017 ActionAid report titled, The AMV: Are we repackaging a colonial paradigm?

“By ramping up models of maximum extraction, the AMV once again stands in direct opposition to our own priorities to ensure resilient livelihoods and securing climate justice. And it does not address the structural causes of structural violence experienced by women, girls and affected communities,” it says.

Perhaps community-based opposition is more effective. According to the Bench Marks Foundation, in a pamphlet prepared for the civil society Alternative Mining Indaba (AMI) in Cape Town this week, “Intractable conflicts of interest prevail with ongoing interruptions to mining operations. Resistance to mining operations is steadily on the increase along with the associated conflict.”

The AMI’s challenge is to embrace community resistance, neither retreating into narrow NGO silos nor ignoring mining’s adverse impact on energy security, climate and resource depletion.

In 2015, when all new mines were valued at $80bn, Anglo American CEO Mark Cutifani conceded, “There’s something like $25bn worth of projects tied up or stopped” by critics.

Africa desperately needs diversification from mining, but governments remain influenced by trans-national corporations intent on extraction

Meanwhile, the World Bank still attracts intense protest. Women from Marikana’s slums, organised as Sikhala Sonke, remain disgusted by the bank’s $150m financing commitment to Lonmin. From 2007-12, the bank considered the company its “best case” for community investment — until the police massacre of 34 workers there during a wildcat strike. (World Bank president Jim Yong-kim even visited Johannesburg two weeks after that, but didn’t dare mention, much less visit, his mining stake.)

The bank’s other local operations included generous credits to the apartheid regime; relentless promotion of neo-liberal ideology after 1990; a corrupt $3.75bn Eskom loan in 2010 (the largest-ever World Bank project loan, which funds the world’s most polluting coal-fired power plant); and lead-shareholder investments in the Cash Paymaster Services-Net1 rip-offs of SA’s 11-million poorest citizens that receive social grants.

In spite of revelations about trans-national corporation exploitation in The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018, an increasingly schizophrenic World Bank is a sponsor of this week’s African Mining Indaba at Cape Town’s convention centre.

Each year, it’s the place to break bread and sip fine local wines (though perhaps not water in this climate-catastrophic city) with the world’s most aggressive mining bosses and allied African political elites, conferring jovially about how to amplify the looting.

Bond teaches political economy at the Wits School of Governance. He is the author of Uneven Zimbabwe: A Study of Finance, Development and Underdevelopment, and co-author of Zimbabwe’s Plunge: Exhausted Nationalism, Neoliberalism and the Search for Social Justice.