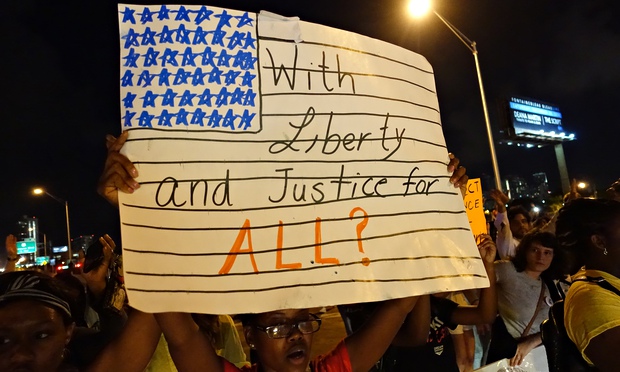

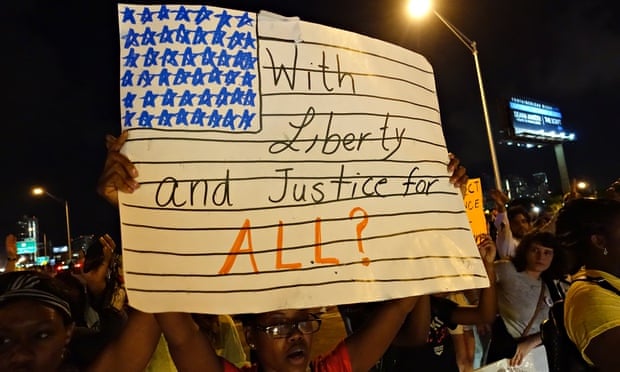

A woman holds a placard in Miami during a protest against police killings Photograph: Steve Rhodes/Demotix/Corbis

The highly publicised killing of Michael Brown, a young black man, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, last August was a dreadful event that led to violent local protests and expressions of outrage across the US. The shooting last month, again by a white police officer, of a 12-year-old black boy, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio, provoked a similar outpouring of fury and grief. Now the case of Eric Garner, also black, who was choked to death when New York police officers, also white, arrested him, has proved a tipping point. The ensuing nationwide uproar has produced numerous spontaneous demonstrations that continued into the weekend.

The protesters’ prime target is egregious police violence and abuse, which seems to many Americans to be endemic and deeply threatening. The broader concern is a justice system that routinely discriminates against racial minorities. In the words of commentator Vincent Warren, the main issue is “systemic, institutional racism in police forces throughout our country”, underpinned, unwittingly or otherwise, by legal and court processes that typically favour the appointed agents of law and order over the rights and protections of the ordinary citizen.

It was not the circumstances surrounding Garner’s death that provoked street “die-ins” in New York and elsewhere, but the incomprehensible decision of a grand jury not to bring charges against the police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, whose chokehold, recorded on video, killed him. A similar decision in Ferguson not to prosecute Darren Wilson, who shot Brown, also sparked calls for reform. Even in a heavily armed nation with a strangely permissive approach to gun violence, this confluence of three high-profile, lethal injustices had a shocking impact. The American justice system gave the world the benchmark, “three strikes and you’re out”. On this basis, heads should roll. Someone, surely, should pay?

Apparently not. The official response to the killings, from Barack Obama and the attorney-general, Eric Holder, downwards, has been dilatory, dispassionate and disappointing. The president cuts a dispirited figure in these post-midterm days. There was a gap, he said, between America’s “professed ideals” and the day-to-day reality facing minority groups trapped by poverty, poor housing, failing schools and persistent discrimination. But there had been “commissions before, there have been task forces, there have been conversations and nothing happens”, he lamented. So what could be done? Obama’s solution was to set up yet another task force, to investigate the Garner case. This in addition to the two ongoing Justice Department inquiries in Ferguson.

Such a half-hearted approach will not do. Police violence, particularly involving black people, is a recurring national problem. So, too, is racial discrimination. According to the Ferguson Action network, set up after Brown’s death, a black person in the US “is killed by someone employed or protected by the US government every 28 hours”. In Cleveland, where Tamir Rice died, police were guilty of using “excessive and unreasonable force” in up to 600 incidents investigated before 2013. Police forces in New Orleans, Seattle, Albuquerque, Oregon, Connecticut, Puerto Rico and Warren, Ohio, are all supposedly implementing reforms after accusations of systematic civil rights violations.

Repeated failures by the justice system to treat black people equally, the misuse of prisons to disproportionately incarcerate young blacks, the “militarisation” of police forces through their acquisition of lethal, army-style equipment, a culture of impunity among law enforcers emboldened by an oppressive, post-9/11 security mindset, the inability of federal and state governments to oversee autonomous city police forces and the failure of a polarised national body politic to address minority concerns comprise the national backdrop to the recent killings.

Only a truly national reform programme can begin to eliminate abuses. Ferguson Action’s manifesto is a good starting point. Its demands include a comprehensive, Cleveland-style review of local police departments, the publication of race-related data, uniform best practice standards and community-based alternatives to incarceration. Most importantly, perhaps, the manifesto calls on Obama to initiate “a national plan of action for racial justice”. Obama should listen. For a disempowered president nearing the end of his term, and as the first black man to occupy the White House, what better way to leave his mark?