A protester carrying a U.S. flag leads a chant during a Black Lives Matter march in Valley Stream, New York, July 13, 2020 (AP photo by John Minchillo).

By Brandon R. Byrd, World Politics Review —

At approximately 8:19 p.m. on the evening of May 25, Derek Chauvin, a 19-year veteran of the Minneapolis Police Department, brought his weight down upon George Floyd’s neck. Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, arrested for the alleged crime of using a counterfeit $20 bill, struggled for breath—for life—for more than five minutes. Lying prostrate on the hot concrete, his arms handcuffed behind his back, his airways choked by Chauvin’s knee, Floyd summoned the strength to tell shocked bystanders that his life was slowly leaving his body. Twenty times he told his executioners, “I can’t breathe.” Twice he called out to his mother, who had passed away in 2018.

Floyd lost consciousness. He joined his mother. Chauvin’s knee stayed on his neck for another three minutes.

The next day, as visceral images and videos of Floyd’s agonizing final moments went viral, a movement began. On May 26, residents of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area created a memorial at the corner store where Chauvin had murdered Floyd. A rally became a march to the local precinct headquarters of the Minneapolis Police Department. An uprising took shape; communities across the United States soon swelled its ranks.

By the middle of June, protests had erupted in thousands of towns and cities across all 50 U.S. states. At rallies and marches, vigils and mass meetings, first-time protesters and seasoned activists mourned and mobilized in remembrance of Floyd and other Black Americans who have been killed by police or white vigilantes, including Ahmaud Arbery, who was pursued and slain in February by a white former police officer and his son, and Breonna Taylor, who was shot to death by police who burst into her home with neither warning nor probable cause in the early morning hours of March 13.

The protesters called their names, cried out “Black Lives Matter.” And people the world over added their collective voice to the chorus. To date, protesters, many of African descent, have organized mass demonstrations in more than 60 countries. People on every continent except Antarctica have stood in solidarity with Black Americans.

With these protests, another link has been forged in a long historical chain of radical internationalism. For more than two centuries, enslaved, colonized and oppressed people and their allies have mobilized across national and imperial borders to challenge racism, colonialism, capitalism and other forms of systemic injustice. Working in solidarity with their counterparts in other nations and colonies, these abolitionists, civil and human rights activists, and anti-colonial dissidents have mobilized to draw foreign support to domestic emancipation projects, highlighting local instances of global problems and adapting global strategies and sounds of resistance to suit local needs.

This global uprising has built on the strong foundations provided by the historical global Black liberation struggle to articulate a more expansive vision of justice.

Today’s protesters in Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania and North and South America are building on this internationalist tradition by connecting their condemnation of U.S. racism and state violence to their own longstanding grievances with the racism and state violence perpetrated by their own governments and police. In Australia, tens of thousands of protesters have rallied on behalf of Floyd and the hundreds of Indigenous Australians who have died in police custody in the past decade. Demonstrators in France and Canada have called attention to anti-Black state violence in their own countries, disabusing their governments of the notion that racial and socio-economic injustice are uniquely U.S. problems. In Haiti, peasant organizations have expressed solidarity while pointing out that the U.S. not only trained Haiti’s existing police force, known for its violence, as part of the United Nations Civilian Police Mission, but also helped create Haiti’s modern military apparatus during its occupation of the country from 1915-1934.

In short, this global uprising, like internationalist mobilizations before it, has linked anti-racism to a broader critique of imperialism, settler colonialism and capitalism. It has built on the strong foundations provided by the historical global Black liberation struggle to articulate a more expansive vision of justice.

Trans-Atlantic Abolitionism, Pan-Africanism and Interwar Internationalisms

The roots of today’s internationalist protest lie in the 19th century, in an era when nationalism was otherwise ascendant around the world. Abolitionists in the United States, including African Americans, recognized the persistence of U.S. slavery as a manifestation of a global problem that was intrinsically linked to other forms of racial and socio-economic oppression. They expressed solidarity with Native Americans, whose dispossession led to the relentless expansion of slavery across the United States, and with European immigrants, whose adoption of anti-Black racism was, in part, a troubling response to their own experience of xenophobic prejudice and discrimination.

U.S. abolitionists also lent support, especially in public writings and speeches, to European labor movements, the democratic revolutions that swept across Europe in 1848 and anti-colonial movements and uprisings in Ireland and India. In the words of historian Manisha Sinha, U.S. abolitionists voiced a radical, universal understanding of emancipation that “included not only the abolition of slavery but also the liberation of all oppressed people” at home and abroad.

These abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, formed particularly strong bonds with British reformers. Great Britain had abolished slavery in its colonies in 1833, and then ended a subsequent period of “colonial apprenticeship”—during which formerly enslaved people were required to work for their former enslavers—in 1838. U.S. abolitionists celebrated emancipation in the British West Indies, and, from the 1830s to the 1860s, traveled to Great Britain to ask the British public to pressure the United States to abandon its increasingly singular commitment to chattel slavery. Along the way, they connected their struggle for freedom to that of workers in Great Britain, including the Chartists, the working class movement that aimed to enfranchise British laborers.

By 1846, Douglass and Garrison had joined with British abolitionists and members of the London Workingmen’s Association, a foundational Chartist organization, to establish the London-based Anti-Slavery League. The league was modeled on the Anti-Corn Law League, an organization that had worked to repeal legislation that had levied a high tax on grain imports, raising the price of bread and enriching British landowners at the expense of workers. According to Douglass, the new league gave “a new object and impetus to the abolitionists.”

In 1858, another Black abolitionist, Sarah Parker Remond, embarked on her own anti-slavery lecture tour in Great Britain. Her speeches, like those of her peers, attracted thousands of British people, many of them laborers who suffered deplorable, sometimes fatal conditions in British factories. Reflecting on the connections between the U.S. plantations where enslaved people produced cotton and the British factories where workers turned that cotton into finished textiles, Remond noted that “the free operatives of Britain are, in reality, brought into almost personal relations with slaves in their daily toil.” Some, she suggested, were drawn to the anti-slavery struggle by the recognition that “they manufacture the material which the slaves have produced.”

If a nascent critique of capitalism inspired early interracial, transnational solidarities, so did an awareness of the link between colonialism and slavery. For example, during the 1830s and 1840s, U.S. abolitionists, including Garrison, befriended Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell and made a concerted effort to support Irish independence from Britain. In turn, many Irish people—particularly opponents of the 1800 Act of Union, which had dissolved the Irish Parliament and merged Ireland and Great Britain into a single kingdom under the British monarchy—voiced abolitionist sensibilities. In 1841, when Charles Lenox Remond, the brother of Sarah Parker Remond, returned to the United States after his own British lecture tour, he brought with him a petition urging Irish immigrants in the United States to “UNITE WITH THE ABOLITIONISTS.” It was signed by O’Connell and more than 60,000 of his compatriots.

Through their commitment to internationalism, 19th-century abolitionists and their allies set an essential precedent that was expanded by the next generation of Black activists. During the 1870s, thousands of African Americans, including members of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee, petitioned the U.S. government to support emancipation and national independence in Cuba. At the turn of the 20th century, Black activists also established anti-imperial organizations in solidarity with the colonized “brown peoples” of the Philippines, and raised alarms about the European scramble for colonies in Africa and Asia, which was formalized at the Berlin West Africa Conference of 1884-1885. To these internationalists, there were clear connections among Europe’s violent push for guaranteed sources of raw materials, cheap labor and markets for finished products in Africa, Asia and the Middle East; the extension of U.S. financial power through the rapid expansion of U.S. empire in the Caribbean and the Pacific; and the continued extraction of Black labor in the U.S. South, where slavery had been supplanted by a new racial caste system, convict leasing and lynching.

The Pan-African Conference of 1900, held in July of that year in London, offered a historic opportunity for colonized and oppressed, but nonetheless resistant, Black people to recognize their shared conditions and join in common cause. The organizer, Henry Sylvester Williams, a Trinidadian barrister who had founded the advocacy group the African Association, invited delegates from Africa, the United States and the Caribbean to speak at the conference on a range of subjects, including the British empire’s use of forced labor in Rhodesia—modern-day Zambia and Zimbabwe—and South Africa, anti-Black discrimination in the British West Indies, and “The Negro Problem in America.”

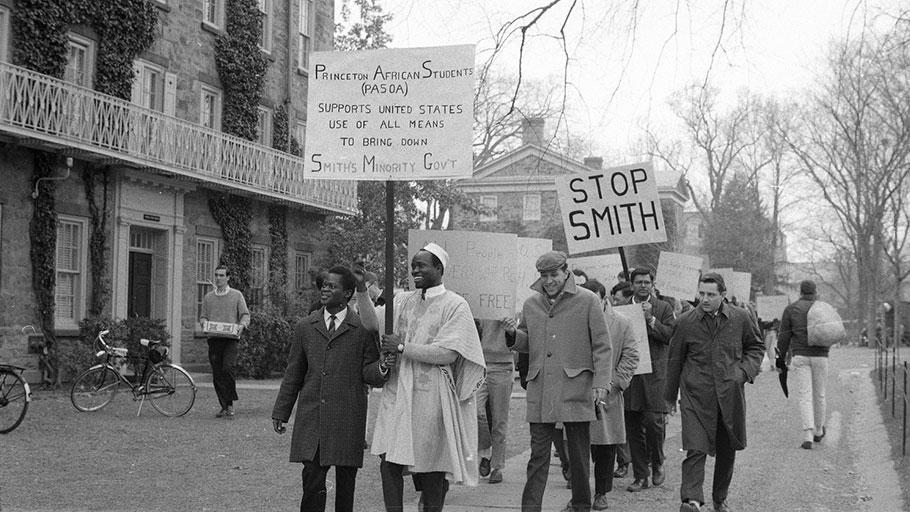

A protest against Ian Smith, the leader of Rhodesia’s predominantly white government, in Princeton, New Jersey, Nov. 12, 1965 (AP photo).

The conference culminated in the unanimous adoption of an “Address to the Nations of the World,” a document drafted by the prominent U.S. civil rights activist and social scientist W.E.B. Du Bois, that was then sent to the leaders of the world’s imperial powers. It demanded that the United States and Europe “acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent” and respect the sovereignty of “the free Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, etc.” And it contained Du Bois’s most prophetic words: “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line.”

The international political solidarities forged at the Pan-African Conference flourished between World War I and World War II. In this interwar period, Black activists the world over upheld the political urgency of Pan-Africanism—the idea that people of African descent share a common heritage, struggle and destiny. Pan-African congresses and new organizations, including Marcus Garvey and Amy Ashwood Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, offered expanded avenues for Pan-African solidarity. By the early 1920s, the UNIA claimed 6 million members in 2,000 divisions in more than 40 countries. These “Garveyites” adapted the UNIA’s anti-colonial politics, and its emphasis on Black political and economic self-determination, to their local efforts to challenge colonialism, apartheid and Jim Crow segregation.

Indeed, throughout this period, anti-racism became ever more connected with critiques of capitalism. In the wake of the Russian Revolution, the Communist International—the Soviet organization devoted to promoting communism around the world, known popularly as the Comintern—declared its support for anti-colonial struggles in Africa and Asia. Activists from both continents, including the Indian revolutionary M.N. Roy, were instrumental in transforming the Comintern into a space for anti-colonial struggle. Fellow radicals such as George Padmore, the Trinidadian leader of the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers, also employed Marxist analysis in the service of Black and colonial liberation. As historian Minkah Makalani writes, Black radicals consistently linked decolonization and desegregation to a universal project of emancipation by insisting “that whether humanity enjoyed greater freedoms … hinged on the struggles that peoples of African descent in the United States, Caribbean, and Africa would wage against racism, colonialism, and capitalism.”

Their cause was truly the world’s.

The Global Struggle for Desegregation and Decolonization

During the interwar period, the U.S. occupation of Haiti emerged as a particularly important target of protest.

For people of African descent and some of their allies, Haiti had become a powerful symbol of Black self-emancipation and independence ever since 1804, when it succeeded in throwing off the yoke of slavery and French colonialism to become the first independent Black nation in the Western Hemisphere. After the United States invaded Haiti in July 1915, beginning a military occupation that would last until 1934, many African American and Caribbean activists in the United States felt that anti-occupation protest was needed not only to restore the sovereignty of a singular example of Black independence, but also to dramatize their own claims to freedom and full citizenship at a time when racial apartheid was becoming ever more entrenched in the U.S. As proclaimed in leaflets distributed by one anti-occupation organization led by African Americans, “the cause of Haiti and our cause is a common one.”

Haitian activists encouraged these international ties, forging connections with the U.S.-based National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, International Council of Women of the Darker Races of the World and UNIA. In public demonstrations, Haitian demonstrators wielded signs asking, “Shall Haiti Be Your Ireland?” and “Shall Haiti Be Your Congo?” Comparing the U.S. military occupation of Haiti with Great Britain’s violent suppression of independence in Ireland and Belgium’s genocidal rule in the Congo disabused U.S. Americans of the misguided notion that their government was “democratizing” Haiti. It reinforced the Haitian claim to independence, which, like other anti-colonial movements, was strengthened by and supportive of international alliances.

“There is no kind of action in this country that is ever going to bear fruit unless that action is tied in with the overall international struggle.”

Similar solidarities would abound in an era when the fate of democracy and the “darker races of the world” hung in the balance. In 1935, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, one of only two independent African states, outraged the Black world. Dockworkers in Trinidad and South Africa refused to offload Italian cargo. Members of the Nigerian Youth Movement formed a solidarity group, the Lagos Ethiopia Defense Committee, while London-based Black activists, including Padmore and Amy Ashwood Garvey, established another advocacy organization, the International African Friends of Ethiopia.

From Accra to Detroit, thousands of Black people volunteered to join the fight for Ethiopian freedom against Italian fascism. Soon after, hundreds of African American and Caribbean soldiers—most of them members of the Communist Party or its affiliate organizations—fought with the Second Spanish Republic against fascist rebels led by Gen. Francisco Franco. It was, in essence, a rehearsal for World War II, when thousands of Africans, African Americans and West Indians joined the war against the Axis Powers.

One Jamaican soldier, who served as a chief mechanic during the Spanish Civil War in the Communist International’s International Brigades, explained in a letter to his wife that expansive, world-making ambitions moved Black soldiers to join wars against European fascists:

Because, my dear, we have joined with, and become an active part of, a great progressive force on whose shoulders rests the responsibility of saving human civilization from the planned destruction of a small group of degenerates gone mad in their lust for power. Because if we crush Fascism here we’ll save our people in America, and in other parts of the world from the vicious persecution, wholesale imprisonment, and slaughter which the Jewish people suffered and are suffering under Hitler’s Fascist heels.

To him, and to his fellow Black soldiers, the fight against European fascism was the fight for Black freedom. Victory over Hitler would mean the chance to build a truly democratic world, rather than returning to one founded on genocide and slavery.

The Fifth Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester, England, in October 1945 marked a watershed moment in the struggle for this different world. At a time when the collapse of European empires seemed more imminent than ever, the congress brought together more than 200 delegates from across the Americas, Asia and Africa, including trade unionists and African nationalists who would play decisive roles in dismantling the British empire. Kwame Nkrumah, who went on to become Ghana’s first post-independence president, participated. So did Jomo Kenyatta and Hastings Banda, the first heads-of-state of post-independence Kenya and Malawi, respectively. Alongside Caribbean radicals such as Amy Ashwood Garvey, these African activists imbued the Pan-African movement with a militant spirit of anti-colonial nationalism.

The congress laid the intellectual and organizational basis for a tidal wave of decolonization. By 1968, all of Britain’s African colonies had won their independence. With the notable exceptions of South Africa and Rhodesia, which remained under white-minority governance, these newly independent nations and others went on to collaborate in advancing their interests during the Cold War. In 1955, African and Asian attendees at the Bandung Conference established a “nonaligned movement” declaring their intention to chart a course of neutrality and sovereignty in the struggle for world domination between the Soviet Union and the United States. For a time, the United Nations provided a space from which they could cement solidarities and realize their goals. In 1960, the emergent African bloc in the U.N. secured passage of General Assembly Resolution 1514, the “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.” As Adom Getachew writes, the landmark resolution, which defined foreign rule as a violation of human rights and demanded the immediate end of colonialism, “marked a radical rupture in the history of modern international society.”

A demonstration against South Africa’s racist apartheid system in New York, Aug. 13, 1985 (AP photo by Tito Avilei).

The wave of decolonization across Africa and Asia was cheered by African Americans, most notably Malcolm X, who by then had become one of the most prominent leaders in the United States’ civil rights movement. For Malcolm, the erosion of European empires clarified the global nature of the Black freedom struggle, and introduced new possibilities for the U.S. civil rights movement. He condemned the United States as the last bastion of imperialism and capitalism, and expressed solidarity with Third World people who suffered from the application of U.S. military, political and economic might. He also asked the newly independent Black nations to use their liberated voices to intercede on the behalf of African Americans at the United Nations.

Crucially, Malcolm refused narrow ideas of the local and the national that might impede revolutionary struggle. In June 1964, following an extended tour of Africa and the Middle East, Malcolm spoke at a public rally for his new Pan-Africanist organization, the Organization of African American Unity, or OAAU. “When I speak of some action for the Congo, that includes Congo, Mississippi,” he said, adding that “there is no kind of action in this country that is ever going to bear fruit unless that action is tied in with the overall international struggle.”

Malcolm’s message resonated with many Black Americans. In 1972, Pan-Africanist Owusu Sadaukai, inspired by Malcolm, co-organized the first celebrations of African Liberation Day in the United States. On May 27, approximately 30,000 Black people marched on Washington, D.C., to protest Portugal’s brutal wars to maintain its African colonies and the United States’ continued support for European colonial rule in southern Africa. One flyer distributed before a parallel protest in New Orleans captured the spirit of the day:

New Orleans Wholesale Jewelry imports diamonds from South Africa at the expense of overworked and underpaid black workers. . . Yeah we do have the same enemy which is why a state wide rally is being held.

The Continued Struggle for Freedom

The parallel abolition of legal racial segregation in the United States and emancipation from colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean proved the importance of internationalist politics and protest. And yet, these internationalist movements failed to achieve their loftiest goals, including the improvement of the material circumstances of the world’s working people.

Despite efforts to build a more egalitarian international order and remedy the uneven trade relationships between the Global North and Global South, postcolonial states became subject to neocolonialism, which Nkrumah defined as a structure in which the economic systems, and consequently the governance, of nominally independent states are “directed from outside.” By the 1970s, prices for primary goods, a principal source of revenues for the economies of the Global South, were in a precipitous decline. Amid the ensuing global economic crisis, neoliberalism emerged as an ascendant ideology, promoting a set of economic policies dedicated to the spread of free market capitalism, at the expense of post-colonial nations.

New solidarities arose to meet the crises of the moment. In the early 1970s, the anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and anti-racist ethos and language of the U.S.-based Black Power movement went global. India’s Dalit Panther Movement, for example, derived inspiration and its name from one of the most prominent Black Power organizations, the Black Panther Party.

Perhaps no social movement of the late 20th-century had more success than the anti-apartheid movement. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the British Anti-Apartheid Movement and TransAfrica, the U.S.-based advocacy group behind the Free South Africa Movement, built on earlier international, anti-apartheid protests. Mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people in sustained demonstrations and pressure campaigns, they pushed governments, businesses and consumers to sanction, boycott and divest from South Africa, to great effect. In 1994, their pressure, along with the resistance of Black South Africans, helped bring about free elections and majority rule in South Africa.

Today’s activists and their allies are, like their predecessors, linking their calls for racial justice to global critiques of structural inequality.

Yet, even as transnational activism persisted through organizations such as TransAfrica and the National Black United Front, the challenges facing them grew and multiplied. Throughout the Cold War, the United States had used military interventions and proxy wars in Latin America, Asia and Africa to secure U.S. economic and political power at the expense of “developing” nations, expanding its global military footprint in the process. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the U.S. military had approximately 1,600 bases in 40 countries around the world.

The U.S. financed this expansive project, which activist-scholars such as Angela Davis and Robin D.G. Kelley have long defined as imperial, and the expensive military that carries it out by diverting funding for social welfare programs and public sector institutions—a principal employer of Black workers. As a result, despite gains from the civil rights movement, including in the numbers of Black college graduates, Black Americans continue to suffer from what the scholar Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration and impoverishment.” The Black unemployment rate has increased since 1968 and now remains disproportionately higher than the white unemployment rate. Black Americans are also more than six times as likely to be incarcerated as their white counterparts. And despite making up just 13 percent of the U.S. population, Black Americans constitute more than 30 percent of all people killed by police departments, who use tactics, equipment and personnel imported from the United States’ unending wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Rising to the Occasion, Again

George Floyd’s murder came in the midst of a global pandemic that has disproportionally affected Black, Latino and Indigenous communities, and that has led many to rely on social media for human connection. Countless people in and outside of the United States read the devastating news that came out of Minnesota. Many watched the video showing a Black man dying for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. It required little explanation and no translation. It was immediately recognizable.

It was hauntingly familiar to Black Americans who have experienced the racial retrenchment of the post-civil rights era and Haitians who suffer from the same violence stemming from similar sources in their own country. It struck a nerve with Muslim organizations in the United Kingdom who, having seen their native or ancestral countries ravaged by the “war on terror,” could honestly say to the Floyd family: “Your pain is our pain.”

The outrage was immediate, but this is much more than an isolated moment. The global show of support for Black Americans comes five years after the founding of the Movement for Black Lives, an international coalition of organizations that has brought public attention to local and national manifestations of anti-Black state violence, while reaffirming that “patriarchy, exploitative capitalism, militarism and white supremacy know no borders.” That ongoing movement, led by Black feminists such as Sandy Hudson, the co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto, planted the seeds for today’s demonstrations, tilling ground made fertile by earlier generations of internationalists.

Today’s activists and their allies are, like their predecessors, linking their calls for racial justice to global critiques of structural inequality. They are decrying the inordinate amount of funding police departments receive in the U.S., as well as the militarization of local law enforcement. They are linking the violence of domestic policing to the violence of U.S. militarism. They are denouncing the ways in which policing in all countries acts not in defense of public safety, but for the protection of wealth and enforcement of socio-economic power.

They are writing their part in a long history of international activism. Across the world, protesters are standing together with each other, on the shoulders of those who came before them, to affirm that full liberation for all Black people would entail the liberation of all people suffering under racism, capitalism and all manners of oppression. Today, “Black Lives Matter” is a call for emancipation, in the United States and beyond.

Brandon R. Byrd is an assistant professor of history at Vanderbilt University and author of “The Black Republic: African Americans and the Fate of Haiti.”

Source: World Politics Review