“This will get worse before it gets better.”

It used to be much easier to spot a budding Nazi in the classroom, or at least a student harboring extremist views, says Nora Flanagan, who’s been a public school teacher in Chicago for over 20 years. You’d just look out for the troubled skinhead kid, maybe wearing steel-toed boots and a swastika pin.

Today, it’s more complex. Flanagan and other teachers say that white nationalism, anti-Semitism and misogyny are creeping into their classrooms, often coded in ironic memes and symbols unfamiliar to most adults. Flanagan says she sees extremist messaging more often and more openly than she used to, but “It’s so much more subtle now, and there are so many more things to watch and listen for.”

For example, teachers described students flashing the “OK” sign in class, which has been co-opted by online white supremacists. Others recalled their students changing their computer backgrounds to images of PewDiePie, a popular YouTuber who’s been accused of trafficking in racism and anti-Semitism. Additionally, a slew of recently formed white nationalist groups cultivate a preppy aesthetic to blend into the mainstream.

“It’s right-wing conspiracy theories,” said Flanagan. “It’s subtle code-speak, it’s the symbols they use in their avatars in our online learning platforms, it’s the links they associate with in their bios.”

So, as classes have resumed across the country, teachers are coming to school armed with the “Confronting White Nationalism in Schools Toolkit” to help them spot extremism in the classroom and then try to address it. Since Flanagan, with the help of another teacher in Portland and Oregon-based nonprofit the Western States Center, put together the 50-page toolkit in April, they’ve fielded over 4,000 requests for copies. Teachers, schools, and organizations from every state, plus 18 countries, including Japan, Austria, New Zealand, and Romania, have requested the $10 guide.

“We are seeing young people with no criminal records, from relatively stable families, getting radicalized — mostly on the internet.”

Other teachers say they’re using contemporary literature written from the perspectives of teen refugees or people of color to fight extremism through instilling empathy in their students.

But recognizing subtle expressions of white nationalism isn’t the only challenge. They’re also having to figure out when a student is being subversive — just “for the lulz” — versus when they’re exhibiting symptoms of being radicalized or becoming violent.

For example: A group of nine middle-schoolers in Ojai, California, formed a human swastika on school grounds. Most of the junior class at a high school in Wisconsin did Nazi salutes in their prom photos. And graduating students from two different high schools in Chicago flashed the white supremacist “OK” sign in their yearbooks.

Then there are the students who exhibited anti-Semitic or racist behavior at school and later went on to seek violence. James Fields, from Ohio, was known as the “class Nazi” during high school, and he went on to ram his car into a crowd of protesters during the August 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville.

And when it comes to knowing the difference between subversive and violent intentions, the stakes may be higher than ever.

The web’s dark corners

Teachers were already up against rising hate crimes in schools and mass shootings, and the fall semester comes on the heels of mass shootings in Gilroy, California, El Paso, Texas and Dayton, Ohio. But with the rise of white nationalist recruitment online and mainstreaming of hateful language, they’re now navigating a more complicated and diffuse threat landscape than in years past.

Experts are warning the 2020 election is likely to usher in a new wave of hate and extremism, and this will play out online and across social media where teens spend a large portion of their time.

“We are working to implement programs of understanding and multiculturalism, but what are the kids seeing in their daily lives?”

Far-right extremists have, meanwhile, made no secret of their desire to radicalize young people online. Andrew Anglin, who runs the neo-Nazi site Daily Stormer, has said he hopes to target the “ADHD demographic,” age 11 and up. “It doesn’t make sense to target anyone but young people,” Anglin said on a podcast three years ago.

A 2017 study by James Hawdon, director of the Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention at Virginia Tech, found that 70% of Americans aged 15 to 21 were exposed to extremist messages online (which spiked around the 2016 election), compared to 58% in 2013.

“We are seeing young people with no criminal records, from relatively stable families, getting radicalized — mostly on the internet,” said Brian Levin, who leads the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “The youngest cohort is the most diverse and diversifying, and white nationalism has become a counter-culture response to this diversity.”

The increase in online extremist messaging coincided with a steady rise in reported hate crimes and anti-Semitic incidents at schools. According to the FBI, there were 340 reported hate crimes at K-12 schools in 2017 compared to 158 in 2013. The Anti-Defamation League says the number of anti-Semitic incidents at K-12 schools jumped by 94% between 2016 and 2017, from 235 to 457. Last year, that dipped slightly, but it was still high: The ADL counted 344 incidents in 2018.

All this leaves educators and school administrators feeling outmatched in influencing students who could be vulnerable to radicalization — and in developing constructive ways to fight it.

“We are working to implement programs of understanding and multiculturalism, but what are the kids seeing in their daily lives?” said J, a social studies teacher at a middle school near Portland, Maine. J requested that his name be withheld for this story so that he could speak candidly about his students. “What their friends and social media are teaching them — that’s a powerful opponent.”

So Flanagan and others put together the “Confronting White Nationalism in Schools” toolkit. The pamphlet offers a range of different scenarios, which Flanagan said were drawn from real-life experiences with students.

In one example, a student in a U.S. history class turns in a research paper containing a citation to writings by white nationalist Richard Spencer.

According to the toolkit, teachers should first meet with the student to find out more. Bearing in mind that Spencer writes about history and purposely dresses up his hateful ideas in pseudo-academic language, did the student stumble across his writing and not understand his viewpoints?

If that’s the case, the toolkit proposes that a teacher put together a workshop to help kids learn how to vet source material for bias. If the problem happens more than once, school administrators are advised to work with the school librarians to develop online research guides.

But if the student appeared to cite a white nationalist like Spencer deliberately, the pamphlet suggests that the teacher ask the school counselor whether the student had aired grievances that could explain why they’d be susceptible to being radicalized.

“The early adolescent brain is a sponge, and that is good for some things, but it also means that these kids are absorbing negative language and ideology.“

Hawdon thinks that teachers should try a sympathetic approach in those scenarios that looks at the root cause for why a student could be a soft target for such ideas.

“There’s a sense of economic and social vulnerability that we see with kids expressing support for this,” said Hawdon. “Any attempt to combat this without a nuanced understanding of why kids are feeling this way can lead to a backlash — and make them more entrenched in their beliefs.”

White power movements have previously been associated with economic hardship, but Flanagan isn’t so sure there’s as much of a correlation today. “Historically we’ve looked at kids who are economically disadvantaged,” said Flanagan. “But I’ve seen just as much from kids from privilege, who maybe feel like they’re losing some of that privilege and cultural ground.”

Mainstreaming hate

The normalization of hate poses another significant challenge to educators. J, the middle school teacher from Maine, says he’s especially perplexed by the way white nationalistic language has seeped into the mainstream.

For example, J said he had a few students who were setting images of YouTuber PewDiePie as the backgrounds on their school computers. PewDiePie, who has 100 million subscribers, has often found himself having to apologize for peddling anti-Semitic or racist tropes in his videos.

“PewDiePie is funny, in the 13-year-old humor kind of way, and not everything he does is bad,” J said. “But then he slips in white supremacist statements as if they are facts, and the 13-year-old audience just absorbs it. The early adolescent brain is a sponge, and that is good for some things, but it also means that these kids are absorbing negative language and ideology.“

J said he tried to explain this to his students, with mixed success. “One of the students was polite about it, the other was belligerent,” J recalled. “The next day there was a “Sub for PewdDiePie” sign on the door of my classroom.” J said the sign also said something along the lines of “We can’t let the Indians win.”

Another social studies teacher, who asked to be identified as “L” to allow her to speak candidly about her experiences, was teaching at a rural middle school in Appalachian Ohio until recently. At times, she said, the Trump campaign reared its head in her classroom.

“Even though that community was fairly homogeneous ethnically, there was a sizable population of migrant farm workers who would come for the fall to work on farms, and their children not only worked as well but also attended school,” said L. “We did have some students parroting their parents — or perhaps Trump outright — in chanting things like “Build the wall.”

For L, who now works at a diverse school in Columbus, Ohio, it’s about addressing an incident head-on. “Whenever I encounter xenophobic, racist, misogynist thinking with my students, I try my best to firmly call it out and then have a frank discussion about it.”

An English teacher from a mostly white rural school in Vermont, named “C,” who also requested her name be withheld because of the sensitive nature of the topic, said she noticed a couple students wearing “white lives matter” badges to class. In response, she turned to “Teaching Tolerance,” an Alabama-based magazine launched in the 1990s by SPLC which takes on the thornier culture-war issues facing educators today, including extremism. It also recommends texts for teachers to use in class.

“There is a near-universal consensus among my colleagues and friends: This will get worse before it gets better.”

C’s favorite texts include “The Hate U Give,” by Angie Thomas, which is about a black teenage girl from a poor neighborhood who finds herself embroiled in a national story involving an officer-involved shooting; and Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West,” a young-love story that explores immigration and the refugee crisis.

Some state lawmakers have also been trying to find ways to address the reported uptick in hate crimes and anti-Semitic incidents at schools in their jurisdictions.

In 2017, lawmakers from 20 states pledged to pursue legislation to get laws requiring schools to teach about the Holocaust on the books. Today, at least 12 states mandate some form of education about the genocide, and about half of those laws were signed since 2016.

Flanagan wants to see this issue elevated to the level of national conversation. “There is a near universal consensus among my colleagues and friends: this will get worse before it gets better.”

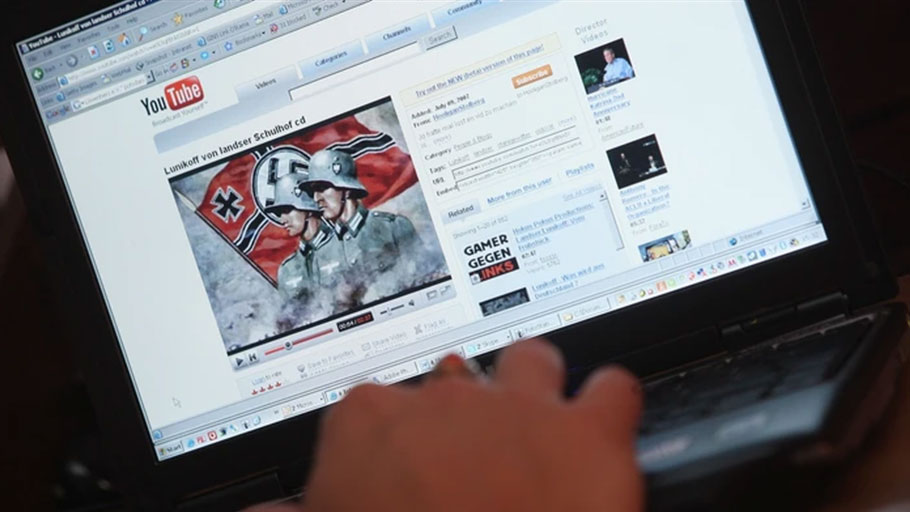

Cover: A video from the German neo-Nazi music band Lunikoff is seen on the website of YouTube August 27, 2007 in Berlin, Germany. German government officials have called for an investigation into YouTube for allowing right-wing groups to use the Internet platform for disseminating neo-Nazi material. (Photo Illustration by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)