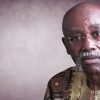

A relief sculpture of the goddess Mami Wata on the wall of a voodoo temple in Benin.CreditCreditGodong/Stockbyte, via Getty Images

The uproar over Disney casting Halle Bailey as the Little Mermaid overlooks generations of Caribbean and African folklore.

By Tracey Baptiste —

As a young child growing up in Trinidad and Tobago within sight and walking distance of the Caribbean Sea, I was gripped by the intrigue of mermaids. I was introduced to one version of a mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen, whose tale of a magical girl creature, an impossible location and an outrageous desire was thrilling.

But I already knew mermaids. We spent most weekends on the beach. There were plenty about. Every cousin, aunt and uncle who threw me in the waves and laugh-shouted at me to swim back to shore seemed to know that we were all part of the sea.

My father, in particular, was a surrogate Poseidon. He would strike out into open water, disappearing for minutes at a time behind huge waves, then appear again, hanging off the side of a fishing boat, where he rested, chatted with the fishermen and then swam back to shore. I didn’t need a Danish fairy tale to tell me that he was part fish. By the time I came across Andersen’s tale, I already knew that mermaids were black and brown people: my family. Besides, what happens when you stay out on the sea? You get darker and darker, deepening to shades of black and brown that glow from absorbing the sun.

It was in this state last week that I first heard about Disney’s decision to cast the black teenage actress and singer Halle Bailey (of Chloe x Halle fame) in the title role for “The Little Mermaid,” and the flood of white people’s tears over it. When the announcement was made, I was swimming in the sea off the Bahamas, getting sunburned as fish swam past me. A lifeguard had just warned me that there were baby sharks about. Was I concerned? Honey, please. This was my natural state.

Back in my hotel room, I turned on my phone for a bit, and several notifications came in, people tagging me in social media posts. The Wi-Fi was spotty, so it was another day or so before I figured out what was going on. I laughed. It was so laughable, this idea that a mermaid couldn’t be black. Didn’t they know?

When I wrote Mama D’Leau into my series of middle grade novels, The Jumbies, I didn’t have to stretch my imagination very far from home. Aiming at kids who don’t know Caribbean folklore, and Caribbean parents who maybe had forgotten it, I reimagined supernatural creatures I had known since I was a child.

Mama D’Leau in the oral tradition was huge and hideous, fierce and unstoppable. She ruled the water, both river and sea alike, and reveled in upturning fishing boats by whipping her powerful anaconda tail and watching her victims drown in the blue. As a young feminist, I was delighted by the idea of such a powerful and free woman, the murder notwithstanding. In my story, I made her as beautiful and well coifed as any of my aunts, and just as fearsome as the stories — or again, any of the aunties.

Mama D’Leau always existed in my imagination. I worried when my father swam out so far that I couldn’t see him, and worried again that the creature would capsize the boat he was hanging on to before he could swim back. In the stories, Mama D’Leau never cared whom she killed. It was sport. Though, same as any fisherman, I suppose. I don’t remember when I figured out that this was only a story.

The story likely started during chattel slavery, when people were kidnapped from the west coast of Africa and brought to the Caribbean and the Americas. The mother of the sea came with them because she already existed in West Africa as Mami Wata, a deity who promised fertility and prosperity to her devotees. It was incredibly good luck to encounter her in person. In West Africa, the goddess was beautiful, sometimes appearing fully as a woman, sometimes as a woman with a fish tail, sometimes with two fish tails. Check your Starbucks cup to see how she’s been co-opted.

But West Africa is not the only place where the idea of a mermaid existed. In Mali, the Dogon people have an origin story involving fish creatures called nommos. The sky god Amma is responsible for creating these half-fish half-people as the first living creatures on earth. Drawings and carvings of nommos exist throughout Dogon culture. In South Africa, the Khoi-san people have stories of mermaids despite living in an arid area.

Water spirits abound in African stories. Water was the thin veil that separated the spirit from the real world, and those who could conquer water were believed to have strong powers. It’s not a surprise that the idea of half-fish half-people would have begun there.

Black mermaids have always existed: long before Andersen, certainly long before Disney. Given the way African stories have been taken and twisted, I wonder just where Andersen got his idea in the first place. He was writing at the height of the colonial period as people were being stripped from African lands, clinging to the stories that made them who they were. The focus on Eurocentric stories and storytelling has done us a disservice, leaving most totally ignorant of the fact that mermaid stories have been told throughout the African continent for millenniums. Mermaids are not just part of the imagination, either, but a part of the living culture.

In the heart of Africa, Africans and people of the diaspora, mermaids are not only real, but there is an inherent sense that they can affect your life, your hopes and your prospects. The idea of this is whispered into our DNA.

We know there are black mermaids. We have seen them. We have been them. They are walking around right now, everywhere, waiting for the sea.

This article was originally published by The New York Times.