Illustration of Maurice Mitchell by Michelle Rohn

Maurice “Moe” Mitchell stalks the stage aggressively, barking lyrics in pointed contrast to his black T-shirt, which reads in bold white letters: “Don’t Shoot.” It’s August 2014, and the socially conscious punk rocker is grieving. Not just because this Afropunk Fest show is his band Cipher’s first in three years after the death of its drummer Danny Bobis, but also because, less than three weeks earlier, the unarmed Black teenager Michael Brown had been shot dead by police in Ferguson, Missouri.

The shooting pushed activists nationwide into the spotlight, including DeRay Mckesson, who would later run for mayor of Baltimore. And there was Mitchell too, a longtime progressive organizer around New York who helped build the strategy that led to Black Lives Matter becoming a ubiquitous phrase. Last year Mitchell was named national director of the Working Families Party (WFP) — a third-party underdog attempting to break up America’s dominant duopoly of Democrats and Republicans.

Maurice “Moe” Mitchell performs at the 2014 Afropunk Fest in Brooklyn.

“Maurice is one of those rare people who brings together deep experience with mass social movements, grass-roots neighborhood organizing and electoral strategy,” says Ana Maria Archila, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy, famous for her confrontation with Republican Sen. Jeff Flake during the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

The party is much more focused on the quiet, down-ballot races that lead

to change down the line.

It’s something that “wasn’t in my life plan,” the fedora-clad Mitchell says, laughing, at the Starbucks in the Marriott Marquis in Washington. Sure, the broad strokes were. While others wanted to be firefighters or astronauts, Mitchell knew that he wanted to “transform society.” He was the middle schooler writing essays about communing with the spirit of Malcolm X, inspired by his parents, who were from Grenada and Trinidad — an immigrant experience akin to the second episode of season one of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, he says. Mitchell’s parents saw their own countries go through moments of intense political upheaval while growing up in the mid-20th century.

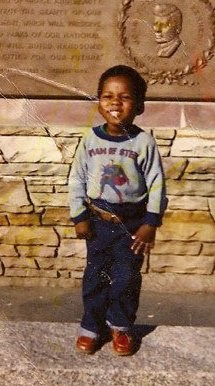

Mitchell in 1983 in Long Beach, New York.

“We were immigrants in America, and we had a sense of pride for the freedom struggle in America but also the freedom struggle in Africa and the Caribbean,” the 39-year-old says, noting that he has been on a singular path toward enacting meaningful change since a very young age (for instance, Mitchell lives a drug-free and vegan lifestyle, and his lyrics are rife with references to feminism and animal rights, which you don’t often find in punk rock).

Only the second national director in the WFP’s two-decade existence, Mitchell has arrived at a pivotal moment. After operating mostly on the fringes of left-leaning politics, the party saw nearly two-thirds of its 1,036 endorsed candidates win state and local offices in 2017. Buoyed by a renewed interest in alternative candidates, as evidenced in the success of Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump on the right, Mitchell led a midterm cycle with some notable wins — defeating conservative Democratic incumbents in New Mexico, Rhode Island and Maryland and contributing to candidates who ended Republican control of the Colorado Senate. Under his leadership, the WFP joined other progressive groups in helping flip the U.S. House of Representatives while supporting insurgent Democrats such as Antonio Delgado in New York and Jahana Hayes in Connecticut.

Mitchell speaks at the Long Island Progressive Coalition in Brentwood, New York, in July 2005.

Perhaps his biggest victory was the party’s work to overthrow the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC) in the New York Senate, eight renegade incumbents who had swung the upper chamber right by caucusing with Republicans. Within a month after the 2016 election, WFP activists were organizing in the districts of the Republican-allied Democrats, talking to voters and releasing a “Resistance Agenda” that became a blueprint for the insurgents the party helped recruit and staff. They were aided by the gubernatorial campaign launched by WFP-endorsed Cynthia Nixon who, despite losing by nearly 30 percentage points in the Democratic primary, forced Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his allies to spend heavily on attack ads rather than on defending the IDC candidates. “She was the recipient of $30 million in negative spending,” says Joe Dinkin, the WFP national campaigns and communications director, “and we ultimately won in six of the eight IDC races.”

The party carries its most weight by far in New York, but it’s increasingly focused on going national. By targeting state legislative seats where a few progressives can change the balance of power — such as Pennsylvania and possibly Wisconsin, Texas and Arizona, although the party’s 2020 priorities are still in flux — Mitchell hopes to have outsize influence.

Mitchell in Brooklyn, New York. Source: Axel Dupex for OZY

While other organizations receive flashy accolades for endorsing ascendant Democrats such as, say, Georgia gubernatorial hopeful Stacey Abrams (which, to be fair, the WFP also did), the party is much more focused on the quiet, down-ballot races that lead to change down the line. It helped build the early political careers of New York Attorney General Letitia James (the first African-American and first woman to hold the post) and 32-year-old Wisconsin Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes. In June, the party sprang an upset with another rising star, when WFP-endorsed public defender Tiffany Cabán, 31, won the Democratic primary for Queens district attorney.

But that race is itself a sign of how WFP isn’t yet a true third party: It’s fighting within Democratic primaries. It could well have a bigger impact this way. The Libertarians and the Greens nominate their own candidates, who routinely get crushed in general elections. Yet WFP is far from a major brand; even politicians with similar aims — Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for example — remain under the Democratic umbrella. (The WFP, in fact, endorsed Ocasio-Cortez’s primary foe, then Rep. Joe Crowley — thinking he was the safe choice. Party leaders later apologized.)

While the WFP has been mostly a coalition party, where “members” were labor groups and grass-roots organizations, Mitchell hopes it becomes a hybrid that incorporates ordinary people more easily and forms caucuses that challenge the status quo even in Democrat-controlled legislatures. But talking with Mitchell, it’s often hard to pin him on strategy — he clearly prefers to talk spiritually, whether it’s about building “a multiracial populist alignment” or unleashing the “trapped energy” behind the “top vs. bottom divide.” “I don’t know, man. I’m not into metrics — that’s such a neoliberal [concept]. That conversation, those data points aren’t super helpful,” he says.

After an hourlong interview and a follow-up call, Mitchell finally concedes a few strategic points of some substance: that progressives must lead with big, bold ideas like the Green New Deal, government-owned banking systems and trillions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure stimulus. “We have a critical role around building the appetite” for those ideas, he says, as his upstart tries to expand its appeal to a country hungry for change.