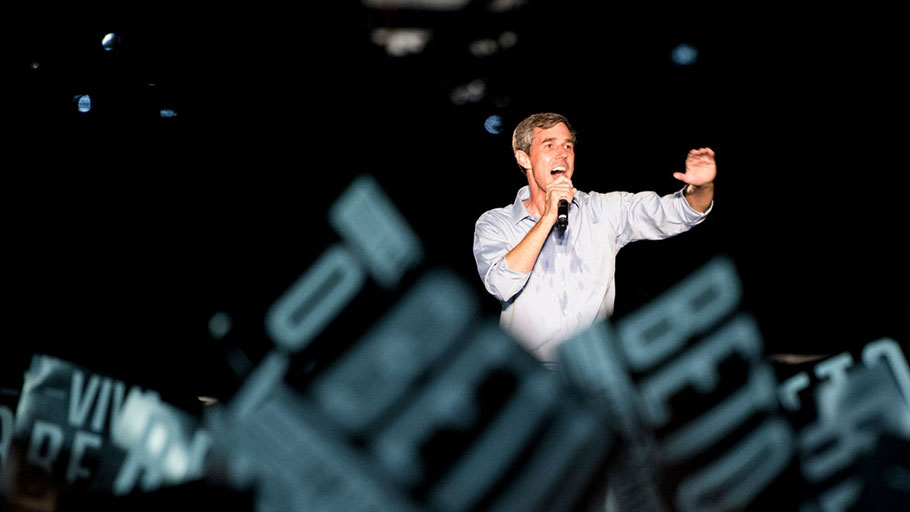

Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate from Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke speaks to the crowd at his “Turn Out for Texas” rally, featuring a concert by Wille Nelson, in Austin, Texas, on Sept. 29, 2018. Photo: Bill Clark, CQ Roll Call, AP

By Briahna Gray, The Intercept —

Just before the new year, Steve Phillips, senior fellow at liberal think tank Center for American Progress, filed paperwork to launch a Super PAC to support New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker’s anticipated 2020 run.

The announcement raises a number of red flags, including about the choice to rely on Super PACs at a time when voters are increasingly skeptical of large campaign donations. But perhaps the most concerning issue is that Phillips’s involvement with Booker’s campaign may represent the further deprioritization of ideology among Democratic politicians.

Let me explain.

The dominant lens through which Philips understands politics is demographic. He is the author of “Brown is the New White,” a New York Times best-seller about how America’s growing nonwhite population is the key to the Democratic Party’s success. Phillips believes that Democrats should prioritize mobilizing nonvoting Americans of color (which it should). But he also argues that Democrats should not “waste money” appealing to white swing voters, derisively rejecting “conventional wisdom” that advocates for “empathy for the anxiety of moderate white voters.” According to Philips, because there is a “ceiling” of white support, courting white voters offers diminishing returns.

Of course, the “demographics as destiny” strategy didn’t pan out in the 2016 presidential election. To the extent that there is a ceiling for white voters set by Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton didn’t reach it — nabbing only 75 percent of the white voters who backed Obama. If she had matched Obama’s numbers among white voters, she would have won, making it difficult to argue that fortifying the Obama coalition would be a “waste.”

The thing is, although much is made of the browning of America, the country is still 70 percent white, and electoral strategies that are wholly dismissive of that population set themselves at an unnecessary disadvantage. America’s “browning” is largely attributed to the fact that Hispanics constitute the largest growing ethnic group in the country. But a majority of Hispanics identify as white, and one third continue to support Donald Trump despite his nativist, anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Americans need a reason to go to the polls — something that makes them feel like their vote matters. Something more than being anti-Trump. Something ideological.

And even if they didn’t so identify, melanin doesn’t guarantee Democratic support. Of the 4.3 million Obama voters who stayed home or voted for third parties in 2016, a third were black. So as important as it is to register voters, ensuring access to franchise is not enough. Americans need a reason to go to the polls — something that makes them feel like their vote matters. Something more than being anti-Trump. Something ideological.

And yet since 2016, the effort to understand the ideological inertia that motivated Trump’s victory has met resistance from establishment Democrats, many of whom, perhaps defensively, limit their analysis of 2016 to Trump’s open bigotry and Russian interference. Recently, this trend has reached absurd levels.

In the course of last month’s Twitter dispute over whether three articles criticizing Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke’s voting record constituted an unfair “attack” from the far left fans of Bernie Sanders, feminist blogger Amanda Marcotte argued that the famously no-nonsense and reclusive senator’s appeal is actually about his charisma, not his politics. “The evidence suggests that [Bernie] Sanders did well in the primaries, not because of his progressive views,” she tweeted, “but because his voters were attracted to a charismatic white guy they viewed as an outsider.” She argued that if charisma and whiteness were all it took to attract a Bernie-sized following, then Beto offers a younger, better option. “Beto is far more that future in 2020 than Bernie,” she wrote.

Journalist Jamil Smith offered a similarly reductive non-ideological take on Sanders’s popularity, suggesting recently that “a significant portion of Bernie’s support came from white guys unwilling to vote for a woman.” In O’Rourke, he argued, those voters might have found “a new white, male candidate.”

In fact, Sanders voters are the least likely to hold bigoted views about black people, according to a widely circulated study depicting the comparative racism of 2016 voters — most coverage of which excluded Sanders voters. Sanders also has the highest approval rating among nonwhites compared to other 2020 candidates. Ignoring Sanders’s long record of anti-racism stretching from civil rights-era protests to his recent bail reform bill, Smith cited the fact that 1 in 10 Sanders voters backed Trump as evidence that Sanders’s appeal is rooted in racism. But the fact that in 2008, Clinton voters were 2.5 times more likely to vote for John “I Hate Gooks” McCain over the first black president is rarely considered to be reflective of the racial equality bonafides of her backers.

Both of these arguments, so plainly errant as to feel like gaslighting, are part of a larger rhetorical trend toward divorcing voter preferences from ideology. Wittingly or not, the effect is to undermine the obvious power of progressive ideas. If Sanders’s appeal can be reduced to charisma, then he can easily be replaced by a younger, more charismatic candidate who is friendlier to big-money interests. If his support is the result of racism or sexism, then his political message can be dismissed as the fruit of that poisonous tree, and other, more diverse candidates can become powerful symbols for anti racism — even if their records betray their commitment to people of color.

As Peter Beinart recently observed in The Atlantic, “The best hope for Democrats who don’t want to purge corporations from the party might be a presidential candidate with a less confrontational economic message who enjoys widespread African American or Latino support. Booker could be such a candidate. So could Kamala Harris or O’Rourke. Which is why skirmishes like the one that pitted the Center for American Progress’s Neera Tanden against supporters of Bernie Sanders will likely only escalate in the year and a half to come.”

Americans firmly agree that the system is rigged, its political institutions are failing the people, and that the American dream — already inaccessible to many due to structural prejudice — is increasingly out of reach.

But here’s the thing: Most Americans do want to limit the reach of corporate influence.

In an increasingly polarized nation, Americans firmly agree that the system is rigged, its political institutions are failing the people, and that the American dream — already inaccessible to many due to structural prejudice — is increasingly out of reach even for the white men who, historically, have disproportionately benefited from it.

I’d argue that the most important American divide to keep in mind going into 2020 isn’t red versus blue, North versus South, coastal versus “flyover,” but insider versus outsider — what Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., renders as the bottom versus the top. The popularity of both Trump and Sanders (and arguably Obama in 2008) suggests that the real silent American majority is this constituency of the aggrieved. If Democrats ignore it, Trump will continue to satisfy many of these voters with nativism and bigotry. The alternative is for Democrats to speak more vividly to their specific concerns: The answer to “they’re taking our jobs” is a Green New Deal, not “America is already great.”

But power brokers in both parties have an interest in minimizing the currency of that broadly shared ideology.

Organizations like Third Way, a centrist think tank founded in 2005 to marry center-right economic policy with center-left social policy, have been leading the charge against ideology as a political organizing tool. In 2017, it commissioned a 23-city bus tour to collect empirical evidence about why Trump won — a “safari in flyover country.” But according to Molly Ball at The Atlantic, who covered the tour, Third Way’s conclusion that voters wanted moderation and pragmatism contrasted with what voters expressed on the ground: “All these centrist ideals,” said one Wisconsin cafe owner, “are just perpetuating a broken system.”

And recently, Third Way tweeted that Sanders’s “ideas were crushed in the midterms” and argued that “Democrats must say no to litmus tests” — in other words, ideological standards by which voters should judge candidates beyond “is a Democrat” or “isn’t one.”

Last Thursday, the anti-ideological trend continued with a Washington Post op-ed by Terry McAuliffe, former governor of Virginia, Democratic National Committee chair, and close affiliate of the Clintons, who argued that “ideological populism” is “playing on Trump’s turf,” and that voters are looking for “realistic solutions.” A federal jobs guarantee, he argued, is “too good to be true,” as is universal free college. “Medicare for All” didn’t even get a mention in his piece. Instead, McAuliffe focused on expanding the Affordable Care Act and curbing high pharmaceutical prices — this despite the fact that 70 percent of all Americans, including a slim majority of Republicans, support “Medicare for All.” Sixty percent of Americans also support free college. And as of this spring, nearly half of Americans support a federal jobs guarantee.

The pragmatic approach is the progressive one.

These numbers indicate that the pragmatic approach is the progressive one — which explains, more than Sanders’s “charisma,” why many top 2020 contenders like Booker, Harris, and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., have shifted left over the last couple years. Voters also appreciate that even explicit commitments to politics can be undermined by monied interests, which is perhaps why these candidates have also taken the no corporate PAC pledge.

But the center-left too often rejects this framing. Rather than credit the critique of O’Rourke, which centered on his breach of a “no fossil fuel” pledge and frequent votes with conservatives — including votes that helped fossil fuel interests — as sincere, it has endeavored to characterize the criticism as a pre-textual attempt to defend Sanders’s status as a uniquely progressive vanguard. Rather than ask what standards the party should have — what litmus test should exist — it blithely blurs the lines, seeing political opportunity in ideological ambiguity.

But a bold, clear ideology is precisely what excites Americans. Look at Ocasio-Cortez, the democratic socialist whose social media feeds have become envy of the entire political establishment. Over the holidays, O’Rourke, Gillibrand, Harris, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., all tried to match the enthusiasm Ocasio-Cortez has piqued around her late-night livestreams during which she cooks dinner and chops it up about policy. But these attempts have fallen short. What these politicians don’t get is that Ocasio-Cortez’s magic isn’t in the medium. It’s in the message.

Ocasio-Cortez understands (more than most pundits) that her victory and subsequent popularity can’t be reduced to charisma or mere demographics. As she (sub) tweeted: “A few social media ideas for public servants looking to build an audience: Endorse Single-Payer Medicare for All. Hold Wall Street Accountable. Make Min Wage = Living Wage. . . Support a Federal Jobs Guarantee, Bail Out Student Debt, Legalize Marijuana & Explore Reparations, Baby Bonds.”

Ocasio-Cortez is a one-woman litmus test generator.

In direct contrast with Third Way’s warning against litmus tests, Ocasio-Cortez is a one-woman litmus test generator. When she takes to Instagram Live or Twitter, she’s setting new standards for transparency that feel fresh and unfamiliar to voters inured to the self-preserving conservatism of politicians. She’s not just cooking. She’s cooking with fire.

Unfortunately, that lesson is far from learned.

To many democrats, the distinction between Sanders and other 2020 hopefuls, including O’Rourke, has become one without much difference. In a recent interview with NBC, Jon Favreau, Obama’s former speech writer, described O’Rourke, Sanders, Harris, and “others” who are likely to run all as “progressives.” Center for American Progress President Neera Tanden repeatedly bristles at any suggestion that the Sanders wing of the party represents a significant ideological departure from her own. “What are you talking about,” she tweeted in response to a journalist’s claim that CAP pulls the Democratic Party to the right. “You don’t get to define what is and is not progressive.”

But while no one writer is an authority on what makes a progressive, the word becomes meaningless if, like Tanden and Favreau, it’s applied evenly to an ideologically broad range of people.

Tanden, for example, would count Hillary Clinton and Justin Trudeau among progressives, despite the former’s reluctance to adopt what have become widely popular programs like single-payer health care and a $15 minimum wage, and the latter’s broadly centrist politics. CAP describes itself as “progressive,” but neither CAP nor its current chair, former Democratic Majority Leader Tom Daschle, have come out in support of “Medicare for All” — despite Daschle once considering single payer to be “inevitable.” Daschel is now a health care lobbyist who was recently named as a potential surrogate for a pharma-backed bipartisan campaign against “Medicare for All.” Is that the face of progressivism?

Adam Serwer at The Atlantic argued recently on Twitter that “Beto people are not irrational or superficial for looking for a candidate who appeals for non-ideological reasons.”

But choosing to support a candidate for reasons other than their ideology — their expressed policy prescriptions — is definitionally superficial. It’s also illogical when you consider that authenticity brings its own rewards. This is a lesson that needs to be learned sooner rather than later. It’s 2019 after all.