To lessen and reverse the pandemic’s effects on Black families’ income and wealth, consciously consider the persistent effects of the country’s legacy of human trafficking, bondage, and disadvantage.

By Kilolo Kijakazi, Jonathan Schwabish and Margaret Simms —

The economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic promises to affect families across the United States and future generations for years to come. The downturn will likely hit African Americans hardest, exacerbating large, long-standing racial wealth gaps. Because these inequities have historical roots, looking at how they contribute to intergenerational inequality can help citizens, policymakers, and stakeholders create policies that move the country toward racial equity.

We cannot start just 20, 50, or even 100 years ago; we need to start at the beginning. Four hundred years ago, white people trafficked and enslaved people of African descent all for the purpose of building their own wealth. Centuries of systemic and structural racism followed, and it was not until 1865 that the 13th Amendment passed and officially released Black people from bondage.

For the next nearly 100 years, Jim Crow laws and discriminatory practices enforced racial segregation and handicapped efforts to reduce or eliminate the racial wealth gap. Restricted covenants and redlining prevented Black people from buying homes in many neighborhoods; the Black Codes prohibited many Black people from establishing profitable businesses, and white mob violence destroyed the businesses of many other Black entrepreneurs; and being denied access to better paying jobs made it more difficult for Black families to accrue savings for down payments on homes or accumulate cash for business investments.

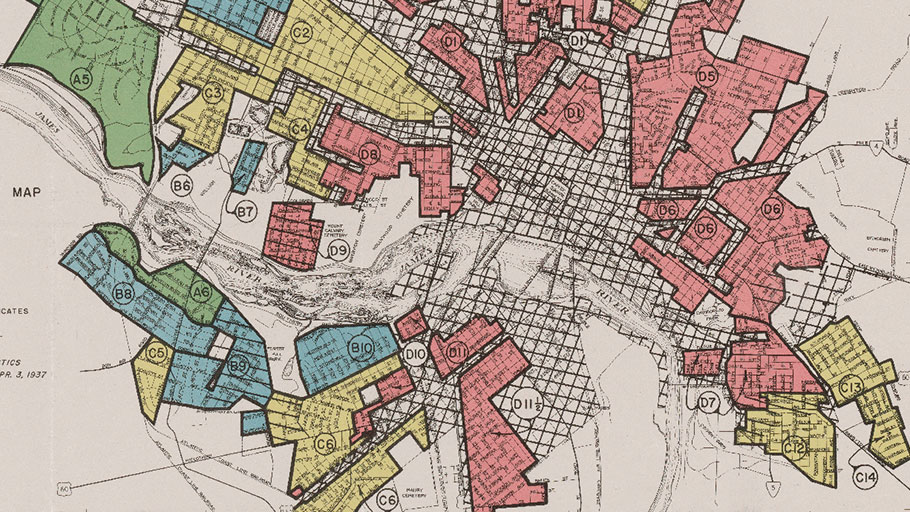

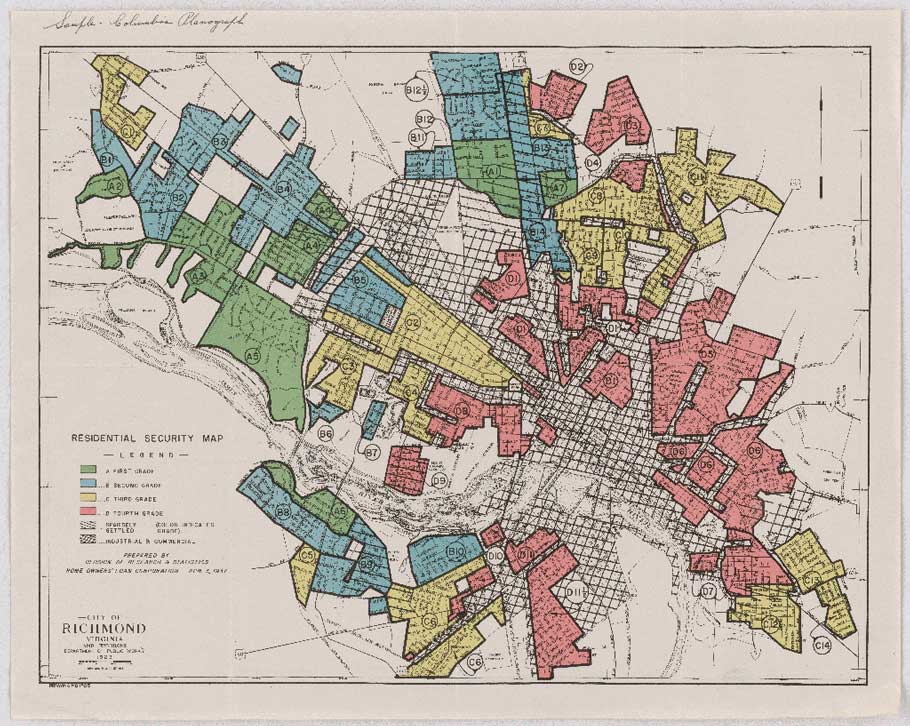

A “redlining” map of Richmond, Virginia, from 1937 produced by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation used to appraise home values and neighborhoods. A neighborhood earned a red color if African Americans lived in the neighborhood, even if the area was solidly middle class. Source: National Archives.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act put Black people on equal legal footing with white people, but they did not put them on equal economic footing. As then-president Lyndon Baines Johnson said in his 1965 speech at Howard University, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others…’.”

Former president Johnson noted that considering Black people on the same initial footing ignores all the barriers that hampered their progress and inhibited them from fair competition in the economy, including the following:

The income gap

Before the Civil Rights Acts, employers could openly discriminate by labeling jobs “for whites only.” Although this practice became illegal in the mid-1960s, structural barriers prevented Black workers from applying for and obtaining jobs, including being excluded from informal networks or living in segregated neighborhoods far from employment opportunities.

Consequently, income differences between Black and white families still exist. In 2018, Black families had 58 percent of the income of white families, virtually the same share as in 1967. Similarly, the poverty rate among Black people (21.7 percent) is more than double that of white people (10.5 percent), indicating that Black individuals and families are less likely to have savings and are more likely to be in need of assistance from relatives and friends who might have some savings. Research shows Black families are more likely to be connected to family members who need financial assistance, further affecting their ability to accumulate wealth.

The wealth gap

The Black-white wealth gap may present the clearest example of how intergenerational transfers can lead to ongoing inequality. In 2016, the average Black household had 10 percent as much wealth as the average white household. Research has shown that this disparity cannot be explained by differences in education, income, or even savings rates. In fact, Black households headed by a person with a college degree have less than 70 percent the wealth of households headed by a white person who did not finish college. Lower-income Black families had $5,000 in median net worth in 2016, less than one-fourth that of lower-income white families ($22,900).

Intergenerational impacts

These income and wealth gaps not only restrict parents’ opportunities for economic advancement but also affect the economic well-being of their children. Two factors influence wealth accumulation and retention: the savings and investment that households accumulate out of current income and the receipt of wealth from family members through gifts or inheritance. Urban Institute research shows that large inheritances or gifts explain about 12 percent of the difference between Black households and white households. A 2018 study estimates that between 26 and 50 percent of total wealth for all households in the United States (not accounting for race or ethnicity) is from gifts and inheritances from parents.

A fundamental reason for the Black-white wealth gap is the Jim Crow period’s restriction of Black wealth three generations ago. Black grandparents’ barriers to accumulating wealth during this era, coupled with the fact that their parents or grandparents were enslaved, created high rates of economic and social disadvantage for future generations. Centuries of bondage, Jim Crow, and their enduring legacies constitute a period of 400 years during which policy, practice, and violence blocked and stripped Black people of wealth accumulation.

COVID-19 has made the effects of past economic disadvantages on employment and savings, housing security, health, and business success of Black Americans especially apparent today. If policymakers want to lessen and reverse the effects of the pandemic on the income and wealth of Black families, they must consciously consider the persistent effects of the country’s legacy of human trafficking, bondage, and disadvantage.

Source: Urban Wire