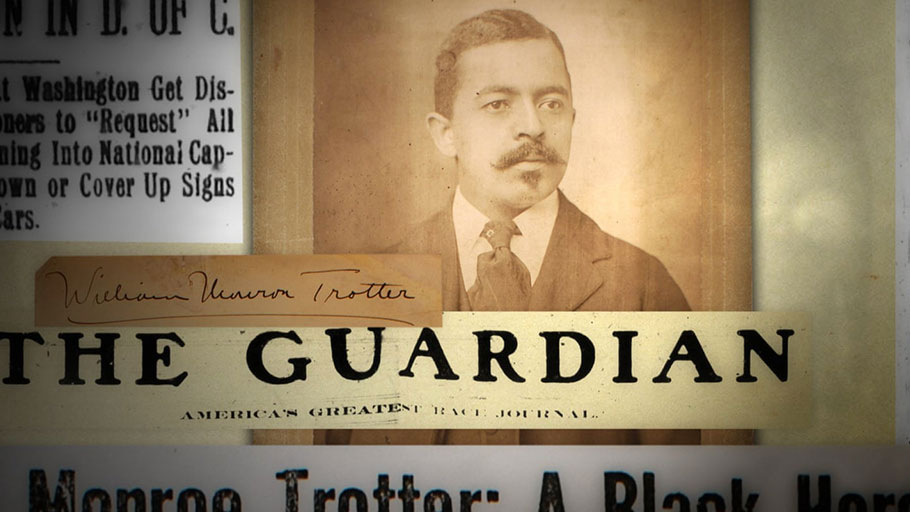

‘Unfortunately for us, there is no William Monroe Trotter in 2020. Nor is there a Boston Guardian demanding that the black press “hold a mirror up to nature”.’ Photograph: Courtesy Northern Lights Production

In 1901, William Trotter founded an other Guardian – the Boston Guardian – to ‘hold a mirror up to nature’. We could use something similar today, writes Kerri Greenidge.

In 1901, William Monroe Trotter founded the Guardian newspaper in Boston. At that time, the more famous Guardian – the one you’re now reading – was published in Manchester, and Trotter had never traveled further than Chillicothe, Ohio. By the time he died in 1934, however, Trotter and the Boston Guardian had a similar effect on transnational black radical politics as the Manchester Guardian had on British liberalism.

Trotter’s vow that the Guardian “hold a mirror up to nature” invoked a black radical tradition rooted in 18th century transatlantic slave rebellion and the militant abolition of African diasporic communities throughout the Americas. The Manchester Guardian, in contrast, supported progressive racial reform of America’s so-called “negro problem” even as it adhered to a liberal tradition that diluted the radical “colored world democracy” that Trotter demanded.

William Monroe Trotter was born in 1872 and jumped to his death 62 years later. He grew up in Hyde Park, then a suburb of Boston proper, and graduated from Harvard in 1895. Despite his comparative privilege, he entered adulthood during the period that scholars refer to as the “racial nadir” of African American history. Southern lynching, disfranchisement, and segregation limited Trotter’s prospects even with a hefty inheritance from his father, and a promising career as a real estate broker.

Trotter pictured in about 1903. Photograph: Courtesy Bancroft Library California.

Although he was offered a job teaching in the segregated south, Trotter’s principles – he refused to bow to Jim Crow laws and their restrictions – made him consider expatriation in Europe where “at least [he] would be treated as a man”. When he founded the Boston Guardian, Trotter was determined to use the medium of the press as it had originally been used when Freedom’s Journal, America’s first black newspaper, was founded in New York in 1827. “Too long have others spoken for us, too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations,” Freedom’s Journal proclaimed at a time when white newspapers and magazines justified slavery’s expansion and Native American removal through images of African inferiority and “Anglo-Saxon” superiority.

Trotter told Boston Guardian readers: “A paper must be known for what it does, not merely what it says. The Guardian is not like most colored weeklies, saying one thing and doing another. We ‘do’ for colored humanity what the world has conspired to deny us. We will not apologize, and we will not retreat – the Guardian makes itself responsible for our collective deliverance. None are free unless all are free.”

Although it is tempting to draw parallels between Trotter’s radical Boston Guardian and the Manchester Guardian, the self-proclaimed “greatest colored newspaper in the world” consciously drew upon a black radical tradition that British progressives were only beginning to acknowledge in 1901. This tradition, as scholars from Cedric Robinson to Robin DG Kelley have shown, demands emancipatory revolution from racial capitalism, centering blackness and decolonization where Marxism centers the struggle between European labor and capital.

For instance, while the Manchester Guardian supported Ida B Wells’ anti-lynching crusade, a racial progressivism that placed Britain far to the left of most white American newspapers, Trotter’s Guardian took this protest a step further. He cited Wells’ statistics and reprinted her intrepid reporting, using her anti-lynching campaign to argue that lynching was “as much the fault of the white mob as the Republican capitalist who is all too happy to sacrifice the negro vote for a mess of southern pottage”.

Leaders of the Liberty League, an activist group, sit for a photograph in 1918. Trotter is fifth from right in the front row. Photograph: Hubert Harrison Papers Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University.

In 1919, the Boston Guardian raised money to send Trotter to the Versailles peace conference as a “representative of colored world democracy”. Although Trotter was denied a passport, the fundraiser paid for his passage to France, disguised as a cook, where he presented “demands for colored world democracy” that were later published in the European press.

The “demands of the colored people” never made it in to the Treaty of Versailles, and Trotter and the Boston Guardian barely registered as a footnote in traditional narratives of African American politics during the first world war.

But it behooves us to take seriously his radical political uses of black newspapers, and to use the press as Trotter used it – to expose truth, unapologetically and persistently, on behalf of those who are most abused by the global political, economic, and cultural systems in which we live.

The newspaper and political culture in which Trotter published the Guardian bears a striking resemblance to our own time

Throughout his 33 years of grassroots protest – on behalf of the Brownsville soldiers in 1906, against the racist film The Birth of a Nation in 1915, and in support of a federal anti-lynching bill in the early 1920 – Trotter’s success must be measured by the permanent effect that he and the Boston Guardian had on black radical consciousness. In its support for a grassroots, community-led public protest against DW Griffith’s film, for instance, Trotter urged his supporters to move beyond the argument, posited by various progressives in the NAACP, that The Birth of a Nation’s glorification of the violent Ku Klux Klan represented a misunderstanding of history rather than the white supremacist, anti-black propaganda that Griffith intended.

The Birth of a Nation ignited white hatred and violence, Trotter argued, and therefore his protest relied on mass demonstrations of civil disobedience by black people themselves, not merely legal arguments over censorship and freedom of expression. The film, of course, was not stopped, and its release led directly to reinstatement of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia in 1915, but this does not mean that Trotter’s radical mass protest was a failure.

Trotter could not singlehandedly stop The Birth of a Nation any more than he could revolutionize the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Still, he forced the black press to re-consecrate its radical design – to “agitate, agitate, agitate,” as Trotter told readers, by “holding a mirror up to nature”.

The newspaper and political culture in which Trotter published the Boston Guardian bears a striking resemblance to our own time. During that original Gilded Age, white backlash against southern emancipation and the democratic possibilities of Reconstruction ushered in an era of black disfranchisement, segregation, and lynching. At the dawn of the 21st century’s second decade, we might be living in an age of historically low crime and high employment, but income and wealth inequity, mass incarceration and the desecration of public education are rampant.

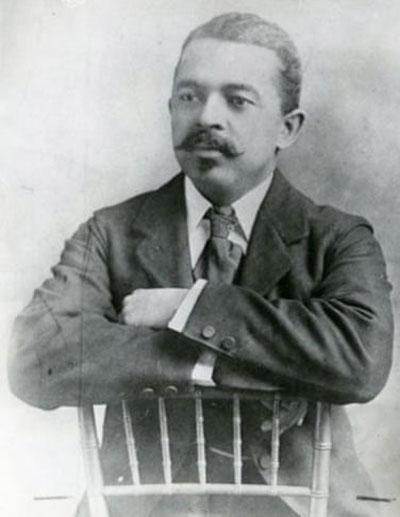

William Monroe Trotter in 1915. Photograph: Wikimedia/Boston city council.

Unfortunately for us, there is no Trotter in 2020. Nor is there a Boston Guardian demanding that the black press “hold a mirror up to nature” by exposing – unapologetically and consistently – the consequences of white conservatism. Of course, there are outlets for a segment of black political and cultural discourse – The Root, for instance, and columns in supposedly liberal outlets such as Slate, Salon, and ProPublica. But the precarious, underfunded, and advertisement-dependent popular black media is often sacrificed by its very structure.

A truly radical black press – a 21st century Messenger, Voice, Crusader, or Guardian, for instance – could combat public ignorance while recognizing its historic and institutional roots; it could sustain radical black community protest even if that protest initially “failed”; it could mobilize citizens against voter suppression in the 2020 election while acknowledging the very real frustrations of those who recognize the structural limitations of the electoral college and corporate control.

Yet Trotter also found it difficult to accomplish these things.By the time he jumped to his death in 1934, the Guardian was poorly managed, nearly bankrupt, and badly written. But it had successfully fomented black radical political consciousness amongst the very people for whom WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington bore little political or personal relevance.

In the words of Cyril V Briggs, a radical Caribbean-born Harlem activist with whom Trotter founded the militant African Blood Brotherhood, the Guardian editor was “the Stormy Petrel of the times, one of the most militant, dynamic, and popular (with the man in the street) leaders of his day. He was utterly selfless in his dedication to the fight for Negro freedom.” Nor was he afraid of associating with “reds”. It is this spirit – politically uncompromising, selflessly rooted in the needs and demands of the “people on the street,” and “unafraid to associate” with those deemed “radical left” – that black media must embrace.

Only then can it become more than a hashtag. In 1921, on the 100th anniversary of the Manchester Guardian, the paper’s editors proclaimed: “The chief virtue of a newspaper is its independence. It should have a soul of its own.”

While this sentiment is far right of the black radical tradition articulated by Trotter’s Guardian in the last century, it should be the baseline upon which 21st-century black journalism proceeds if we are to truly combat the existential, political, economic and environmental crises that plague us in 2020.

This article was originally published by The Guardian.

Kerri Greenidge is the author of Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (Liveright 2019)