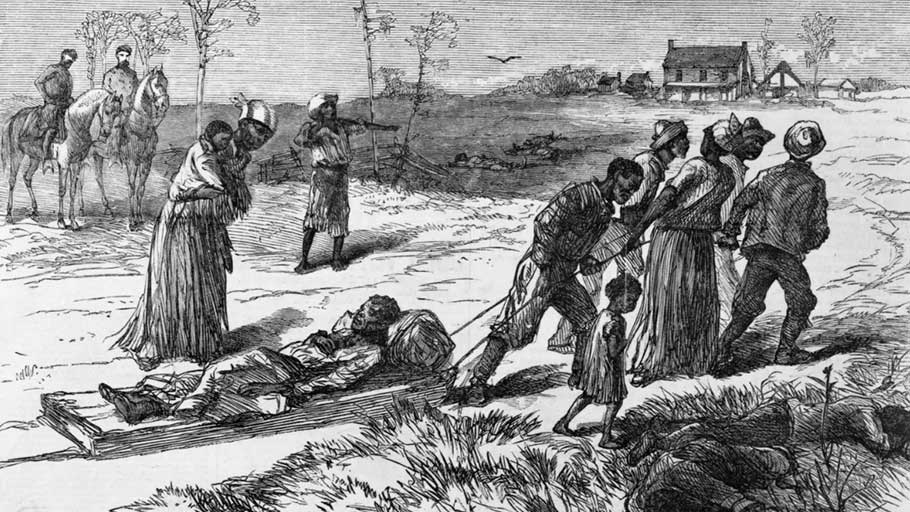

Blacks gathering dead and wounded from the “Colfax Massacre” in Louisiana. Published in Harper’s Weekly, May 10, 1873. (MPI/Getty Images) (Hulton Archive/Getty Images).

From slavery to Reconstruction to Dylann Roof, the idea of “race war” has a long and bloody legacy in the United States.

By Michael E. Miller, The Washington Post —

It was high noon on Easter 1873 when the white mob came riding into Colfax.

Five months earlier, Louisiana had held its second election since the end of the Civil War and the beginning of black male suffrage. But some whites had refused to recognize the result, and former Confederate soldiers had committed acts of racial violence across the state.

When a former slave was fatally shot near Colfax, around 150 black men holed up inside the river town’s courthouse to wait for federal troops.

Instead, they were met by the mob.

“Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy,” one Ku Klux Klan leader told the mob, according to Charles Lane’s “The Day Freedom Died.”

Armed with superior weaponry — including a small cannon — the mob set the courthouse on fire and shot anyone who emerged. When some blacks tried to surrender by waving handkerchiefs, they were mowed down and their remains were desecrated. Anywhere from 62 to 81 African Americans were killed, according to Lane, a Washington Post editorial writer.

“THE WAR OF RACES,” proclaimed a headline in the New York Times.

The Colfax Massacre, as it would come to be known, is one chapter in the long and bloody history of “race war” in America. It is the most radical of racist visions: an apocalyptic ideology driven by the belief that whites are in imminent danger of being wiped out.

Though the ideology peaked during Reconstruction, when the Klan began waging terror to roll back the advances of newly emancipated blacks across the South, it remains very much alive today.

In the past five years, as white supremacy has surged in the United States, experts say there has been an uptick in attempts or plots to spark a race war.

They range from Dylann Roof’s slaughter of nine African Americans at a Bible study in Charleston in 2015 to a hatred-fueled sword attack in New York City in 2017 to the arrest this August of a neo-Nazi in Las Vegas who was allegedly making a bomb to “assist in a race war.”

“There is a tradition of this sort of thinking or fantasizing,” said Mark Pitcavage, an expert on right-wing extremism at the ADL, who called the idea of race war “a staple” of hardcore white supremacy.

The idea of race war tends to resurface “during moments of intense activism against white racism,” such as Reconstruction or, more recently, the Black Lives Matter movement, said Ibram X. Kendi, a professor at American University and the author of “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America” and “How to Be an Antiracist.” By painting themselves as the victims, “defenders of white racism have been able to galvanize large numbers of white people into their organizations.”

A threat older than the United States

The concept is older than the country, beginning not with slavery but with white colonists’ anxiety over being outnumbered by Native Americans, according to Patrick Breen, a history professor at Providence College.

“There was a concern that there would be a genocide if the Indians united,” he said.

That fear then helped fuel centuries of violence against Native Americans.

With the arrival of enslaved Africans to the English colony of Virginia in 1619, the same fear was soon aimed at blacks, especially in states such as South Carolina, Mississippi and Louisiana, where slaves outnumbered or nearly outnumbered whites by the beginning of the 19th century.

The Haitian Revolution, which ended in 1804 with the slaughter of whites who had not fled the former French slave colony, frightened many American slaveholders, Breen said.

“The story they tell themselves — which is not exactly right — was that blacks got in control and began killing whites willy-nilly,” he said.

“Before the Civil War, you had people who argued that whites and blacks could not live together unless it was a situation where blacks were under the control of whites,” Pitcavage said. “They argued that if you had emancipation, you’d inevitably have race war.”

American slaveholders used this threat of a race war in the United States to put down revolts and preserve their power, as in 1831 when whites killed 120 blacks in the wake of Nat Turner’s rebellion in Virginia.

The Porter house at dusk in Southampton County, Va. In 1831 the Porter family was warned about the slave insurrection being led by Nat Turner and left before Turner and his followers arrived. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post )

But some slave owners tried to tamp down on talk of a race war because the likely outcome would have been the extermination of African Americans, according to Breen, the author of “The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood: A New History of the Nat Turner Revolt.”

“Their ultimate fear was that the race war would happen, and they would lose all their property,” he said.

The idea flared up again in the lead up to the Civil War, as John Brown launched abolitionist raids in Kansas and then Virginia.

“John Brown is basically saying, ‘We can launch a race war,’ ” Breen said. The idea had little appeal to African Americans but the raids nonetheless stirred Southerners’ fears.

That trepidation intensified during the Civil War, when many white Southerners went to fight, leaving behind their slaves.

“There are four million slaves on the home front and few white men,” Breen said. “The possibility of having a race war is certainly a concern.”

Sharing that same concern was none other than Abraham Lincoln. The president feared that a guerrilla war by slaves in the South would make it hard to keep the North unified, Breen said. Instead, Lincoln encouraged slaves to escape the South and fight for the Union.

‘Take the government back’

When the Civil War ended, thousands of Union troops stayed in the South to keep order.

Many of them were black.

The presence of armed African American soldiers stoked white Southerners’ fears of a race war and led to false rumors that blacks were about to massacre whites, Breen said.

Instead, it was whites — especially the Klan, created by former Confederate soldiers — who mainly did the massacring.

“The term ‘race war’ was not used then but the equivalent, ‘war of races,’ was very much in the air,” Lane said. “Quite often you’d hear opposition to Reconstruction, and black voting rights in particular, on the grounds that it would trigger a war of races.”

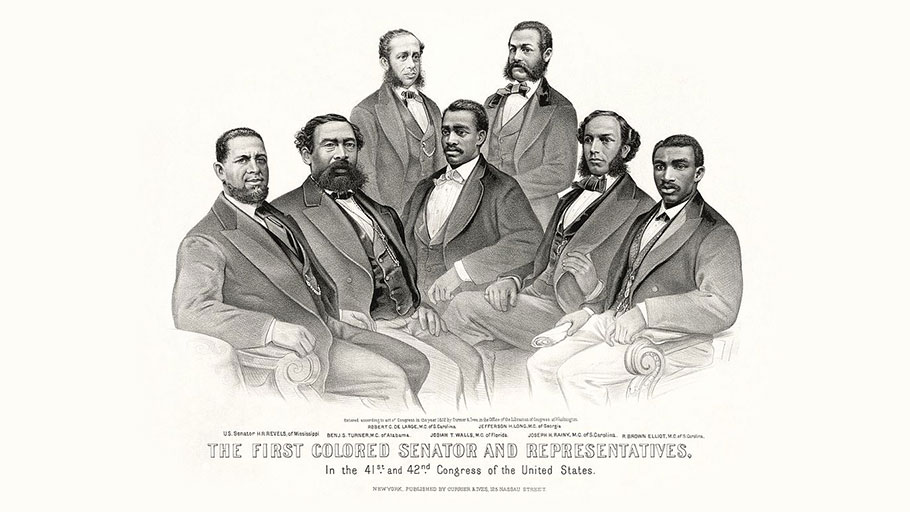

“The First Colored Senator and Representatives.” (Library of Congress)

In Colfax, efforts by black militiamen to confiscate weapons from whites to prevent violence only fed into false claims that blacks were preparing an attack, according to Lane. Then whites “waged a war to literally drive [blacks] out of the courthouse and ‘take the government back,’ ” he said.

By 1876, that’s exactly what had happened across the South, as Klan violence and Jim Crow laws suppressed black voting and allowed white Democrats to retake power.

‘White women have to be protected’

With whites once again in control, there was no longer any threat of blacks waging a literal race war, Breen said. So Southern whites began portraying African Americans as another type of menace.

“Race war isn’t as powerful a motivator” anymore, he said. “What is a powerful motivator is trying to keep blacks in line within the sexual protocol of the south: ‘White women have to be protected.’ ”

That meant lynchings.

The rope that is believed to have bound the wrists of Raymond Byrd, who was lynched in Wytheville, Va., in 1926. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post )

From 1882 to 1968, nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States, primarily black men in the South, according to the NAACP. Many were killed because of false accusations of rape. In perhaps America’s most infamous lynching, Emmett Till was murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman.

Sometimes, race war anxieties weren’t martial or sexual but economic, according to Kendi.

“The projection that black people were battling against white people was used to galvanize support to decimate ‘Black Wall Street’ in Tulsa” and the booming black town of Rosewood, Fla., he said.

Race war largely faded from the national conversation during the civil rights era, when leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. were at pains to portray their efforts as peaceful, Kendi and Breen said. At the same time, white supremacy became less mainstream.

After many of those civil rights leaders were assassinated, however, the rise of the more militant Black Power movement prompted white supremacists to again warn of — and in some cases, try to spark — a race war.

“You have black activists who were very clear that their opposition was to white racism,” Kendi said of the Black Power movement. “The defense from those who did not want to interrogate white racism was to say that these black groups were attacking white people and thereby launching a race war.”

From ‘The Turner Diaries’ to Today

By the late 1970s, white supremacists had shifted from trying to maintain white dominance to warning that the very survival of the white race was at risk.

“From the ’70s onward, white supremacy takes on an apocalyptic tone,” said Pitcavage. “Race war is a part of that.”

Pitcavage sorts white supremacist adherents of race war into three categories. “Reluctant” race warriors don’t want conflict but believe it’s inevitable, so they prepare by stockpiling food and weapons, he said. “Window of opportunity” race warriors may or not desire conflict, but they believe it must happen soon while whites are still in the majority.

Finally, he said, there are “accelerationists” who want to bring about the destruction of society and see race war as a means to speed that up.

That’s what white supremacist serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin was trying to do when he targeted blacks, Jews and interracial couples across the country from 1977 to 1980.

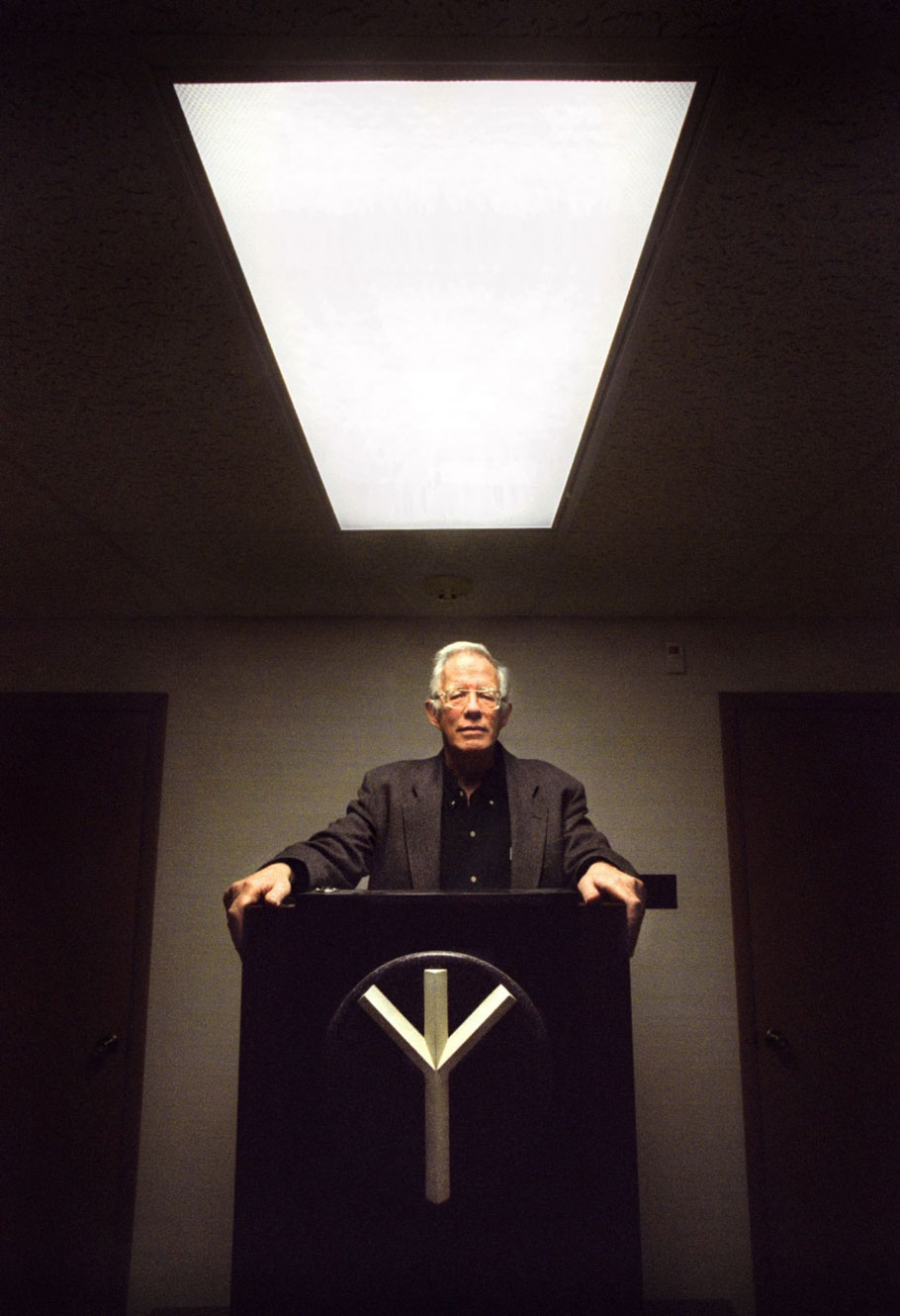

Neo-Nazi leader William Pierce wrote “The Turner Diaries,” which spread the race war ideology. (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

The murder spree inspired neo-Nazi leader William Pierce to pen racist novels “Hunter,” in which one man’s quest to kill interracial couples sparks an uprising, and “The Turner Diaries,” in which such an uprising leads to nuclear war and the annihilation of nonwhites.

The latter book, in particular, would inspire generations of white supremacists, from Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh — who had excerpts of the book in his getaway car — to The Order, a terrorist group that robbed banks, bombed a theater and a synagogue and killed a Jewish radio host in the 1980s.

It was a member of The Order who would later pen the infamous “14 words” from prison.

David Lane’s slogan — “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children” — reflects the demographic anxiety at the heart of white supremacy and its preoccupation with race war.

Thirty years later, America is once again in the midst of a surge in white supremacy, according to Pitcavage and other experts.

Today, “The Turner Diaries” is circulated online. Mobs no longer gather on horseback but on college campuses or, more often, on anonymous Internet message boards.

Although it has evolved somewhat over time, the idea of race war is a common thread that connects the Klan to Charles Manson and Dylann Roof, Lane said.

“Race war is an idea that emerges at certain points in American history and fades at others,” Breen said. “What has made it such a powerful idea, however, is not some real danger of a race war itself, but the politically useful nature of these charges. Politicians have used racially inflammatory rhetoric like this to help them attain power, whether by mobilizing one’s base or suppressing their opponents, but long after the last ballots have been counted, the legacy of the racial demagoguery remains.”

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.